I know what you are thinking. Here’s another article about reducing JavaScript dependencies and the bundle size sent to the client. But this one is a bit different, I promise.

This article is about a couple of things that Bookaway faced and we (as a company in the traveling industry) managed to optimize our pages, so that the HTML we send is smaller. Smaller HTML means less time for Google to download and process those long strings of text.

Usually, the HTML code size is not a big issue, especially for small pages, not data-intensive, or pages that are not SEO-oriented. However, in our pages, the case was different as our database stores lots of data, and we need to serve thousands of landing pages at scale.

You may be wondering why we need such a scale. Well, Bookaway works with 1,500 operators and provide over 20k services in 63 countries with 200% growth year over year (pre Covid-19). In 2019, we sold 500k tickets a year, so our operations are complex and we need to showcase it with our landing pages in an appealing and fast manner. Both for Google bots (SEO) and to actual clients.

In this article, I’ll explain:

- how we found the HTML size is too big;

- how it got reduced;

- the benefits of this process (i.e. creating improved architecture, improving ode organization, providing a straightforward job for Google to index tens of thousands of landing pages, and serving much fewer bytes to the client — especially suitable for people with slow connections).

But first, let’s talk about the importance of speed improvement.

Why Is Speed Improvement Necessary To Our SEO Efforts?

Meet “Web Vitals”, but in particular, meet LCP (Largest Contentful Paint):

“Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) is an important, user-centric metric for measuring perceived load speed because it marks the point in the page load timeline when the page’s main content has likely loaded — a fast LCP helps reassure the user that the page is useful.”

The main goal is to have a small LCP as possible. Part of having a small LCP is to let the user download as small HTML as possible. That way, the user can start the process of painting the largest content paint ASAP.

While LCP is a user-centric metric, reducing it should make a big help to Google bots as Googe states:

“The web is a nearly infinite space, exceeding Google’s ability to explore and index every available URL. As a result, there are limits to how much time Googlebot can spend crawling any single site. Google’s amount of time and resources to crawling a site is commonly called the site’s crawl budget.”

— “Advanced SEO,” Google Search Central Documentation

One of the best technical ways to improve the crawl budget is to help Google do more in less time:

Q: “Does site speed affect my crawl budget? How about errors?”

A: “Making a site faster improves the users’ experience while also increasing the crawl rate. For Googlebot, a speedy site is a sign of healthy servers so that it can get more content over the same number of connections.”

To sum it up, Google bots and Bookaway clients have the same goal — they both want to get content delivered fast. Since our database contains a large amount of data for every page, we need to aggregate it efficiently and send something small and thin to the clients.

Investigations for ways we can improve led to finding that there is a big JSON embedded in our HTML, making the HTML chunky. For that case, we’ll need to understand React Hydration.

React Hydration: Why There Is A JSON In HTML

That happens because of how Server-side rendering works in react and Next.js:

- When the request arrives at the server — it needs to make an HTML based on a data collection. That collection of data is the object returned by

getServerSideProps. - React got the data. Now it kicks into play in the server. It builds in HTML and sends it.

- When the client receives the HTML, it is immediately pained in front of him. In the meanwhile, React javascript is being downloaded and executed.

- When javascript execution is done, React kicks into play again, now on the client. It builds the HTML again and attaches event listeners. This action is called hydration.

- As React building the HTML again for the hydration process, it requires the same data collection used on the server (look back at

1.). - This data collection is being made available by inserting the JSON inside a script tag with id

__NEXT_DATA__.

What Pages Are We Talking About Exactly?

As we need to promote our offerings in search engines, the need for landing pages has arisen. People usually don’t search for a specific bus line’s name, but more like, “How to get from Bangkok to Pattaya?” So far, we have created four types of landing pages that should answer such queries:

- City A to City B

All the lines stretched from a station in City A to a station in City B. (e.g. Bangkok to Pattaya) - City

All lines that go through a specific city. (e.g. Cancun) - Country

All lines that go through a specific country. (e.g. Italy) - Station

All lines that go through a specific station. (e.g. Hanoi-airport)

Now, A Look At Architecture

Let’s take a high-level and very simplified look at the infrastructure powering the landing pages we are talking about. Interesting parts lie on 4 and 5. That’s where the wasting parts:

Key Takeaways From The Process

- The request is hitting the

getInitialPropsfunction. This function runs on the server. This function’s responsibility is to fetch data required for the construction of a page. - The raw data returned from REST Servers passed as is to React.

- First, it runs on the server. Since the non-aggregated data was transferred to React, React is also responsible for aggregating the data into something that can be used by UI components (more about that in the following sections)

- The HTML is being sent to the client, together with the raw data. Then React is kicking again into play also in the client and doing the same job. Because hydration is needed (more about that in the following sections). So React is doing the data aggregation job twice.

The Problem

Analyzing our page creation process led us to the finding of Big JSON embedded inside the HTML. Exactly how big is difficult to say. Each page is slightly different because each station or city has to aggregate a different data set. However, it is safe to say that the JSON size could be as big as 250kb on popular pages. It was Later reduced to sizes around 5kb-15kb. Considerable reduction. On some pages, it was hanging around 200-300 kb. That is big.

The big JSON is embedded inside a script tag with id of ___NEXT_DATA___:

<script id="__NEXT_DATA__" type="application/json">

// Huge JSON here.

</script>

If you want to easily copy this JSON into your clipboard, try this snippet in your Next.js page:

copy($('#__NEXT_DATA__').innerHTML)

A question arises.

Why Is It So Big? What’s In There?

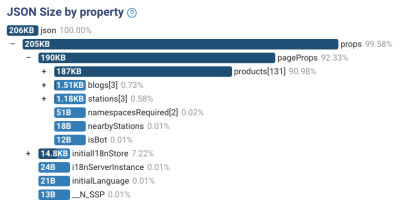

A great tool, JSON Size analyzer, knows how to process a JSON and shows where most of the bulk of size resides.

That was our initial findings while examining a station page:

There are two issues with the analysis:

- Data is not aggregated.

Our HTML contains the complete list of granular products. We don’t need them for painting on-screen purposes. We do need them for aggregation methods. For example, We are fetching a list of all the lines passing through this station. Each line has a supplier. But we need to reduce the list of lines into an array of 2 suppliers. That’s it. We’ll see an example later. - Unnecessary fields.

When drilling down each object, we saw some fields we don’t need at all. Not for aggregation purposes and not for painting methods. That’s because We fetch the data from REST API. We can’t control what data we fetch.

Those two issues showed that the pages need architecture change. But wait. Why do we need a data JSON embedded in our HTML in the first place? 🤔

Architecture Change

The issue of the very big JSON had to be solved in a neat and layered solution. How? Well, by adding the layers marked in green in the following diagram:

A few things to note:

- Double data aggregation was removed and consolidated to just being made just once on the Next.js server only;

- Graphql Server layer added. That makes sure we get only the fields we want. The database can grow with many more fields for each entity, but that won’t affect us anymore;

PageLogicfunction added ingetServerSideProps. This function gets non-aggregated data from back-end services. This function aggregates and prepares the data for the UI components. (It runs only on the server.)

Data Flow Example

We want to render this section from a station page:

We need to know who are the suppliers are operating in a given station. We need to fetch all lines for the lines REST endpoint. That’s the response we got (example purpose, in reality, it was much larger):

[ { id: "58a8bd82b4869b00063b22d2", class: "Standard", supplier: "Hyatt-Mosciski", type: "bus", }, { id: "58f5e40da02e97f000888e07a", class: "Luxury", supplier: "Hyatt-Mosciski", type: "bus", }, { id: "58f5e4a0a02e97f000325e3a", class: 'Luxury', supplier: "Jones Ltd", type: "minivan", },

];

[ { supplier: "Hyatt-Mosciski", amountOfLines: 2, types: ["bus"] }, { supplier: "Jones Ltd", amountOfLines: 1, types: ["minivan"] },

];

As you can see, we got some irrelevant fields. pictures and id are not going to play any role in the section. So we’ll call the Graphql Server and request only the fields we need. So now it looks like this:

[ { supplier: "Hyatt-Mosciski", type: "bus", }, { supplier: "Hyatt-Mosciski", type: "bus", }, { supplier: "Jones Ltd", type: "minivan", },

];

Now that’s an easier object to work with. It is smaller, easier to debug, and takes less memory on the server. But, it is not aggregated yet. This is not the data structure required for the actual rendering.

Let’s send it to the PageLogic function to crunch it and see what we get:

[ { supplier: "Hyatt-Mosciski", amountOfLines: 2, types: ["bus"] }, { supplier: "Jones Ltd", amountOfLines: 1, types: ["minivan"] },

];

This small data collection is sent to the Next.js page.

Now that’s ready-made for UI rendering. No more crunching and preparations are needed. Also, it is now very compact compared to the initial data collection we have extracted. That’s important because we’ll be sending very little data to the client that way.

How To Measure The Impact Of The Change

Reducing HTML size means there are fewer bits to download. When a user requests a page, it gets fully formed HTML in less time. This can be measured in content download of the HTML resource in the network panel.

Conclusions

Delivering thin resources is essential, especially when it comes to HTML. If HTML is turning out big, we have no room left for CSS resources or javascript in our performance budget.

It is best practice to assume many real-world users won’t be using an iPhone 12, but rather a mid-level device on a mid-level network. It turns out that the performance levels are pretty tight as the highly-regarded article suggests:

“Thanks to progress in networks and browsers (but not devices), a more generous global budget cap has emerged for sites constructed the “modern” way. We can now afford ~100KiB of HTML/CSS/fonts and ~300-350KiB of JS (gzipped). This rule-of-thumb limit should hold for at least a year or two. As always, the devil’s in the footnotes, but the top-line is unchanged: when we construct the digital world to the limits of the best devices, we build a less usable one for 80+% of the world’s users.”

Performance Impact

We measure the performance impact by the time it takes to download the HTML on slow 3g throttling. that metric is called “content download” in Chrome Dev Tools.

Here’s a metric example for a station page:

| HTML size (before gzip) | HTML Download time (slow 3G) | |

|---|---|---|

| Before | 370kb | 820ms |

| After | 166 | 540ms |

| Total change | 204kb decrease | 34% Decrease |

Layered Solution

The architecture changes included additional layers:

- GraphQl server: helpers with fetching exactly what we want.

- Dedicated function for aggregation: runs only on the server.

Those changed, apart from pure performance improvements, also offered much better code organization and debugging experience:

- All the logic regarding reducing and aggregating data now centralized in a single function;

- The UI functions are now much more straightforward. No aggregation, no data crunching. They are just getting data and painting it;

- Debugging server code is more pleasant since we extract only the data we need—no more unnecessary fields coming from a REST endpoint.

(vf, il)