In recent years, the field of Content Creation and Representation on Digital platforms has seen a massive disruption. The widespread success of products like Quip, Google Docs and Dropbox Paper has shown how companies are racing to build the best experience for content creators in the enterprise domain and trying to find innovative ways of breaking the traditional moulds of how content is shared and consumed. Taking advantage of the massive outreach of social media platforms, there is a new wave of independent content creators using platforms like Medium to create content and share it with their audience.

As so many people from different professions and backgrounds try to create content on these products, it’s important that these products provide a performant and seamless experience of content creation and have teams of designers and engineers who develop some level of domain expertise over time in this space. With this article, we try to not only lay the foundation of building an editor but also give the readers a glimpse into how little nuggets of functionalities when brought together can create a great user experience for a content creator.

Understanding The Document Structure

Before we dive into building the editor, let’s look at how a document is structured for a Rich Text Editor and what are the different types of data structures involved.

Document Nodes

Document nodes are used to represent the contents of the document. The common types of nodes that a rich-text document could contain are paragraphs, headings, images, videos, code-blocks and pull-quotes. Some of these may contain other nodes as children inside them (e.g. Paragraph nodes contain text nodes inside them). Nodes also hold any properties specific to the object they represent that are needed to render those nodes inside the editor. (e.g. Image nodes contain an image src property, Code-blocks may contain a language property and so on).

There are largely two types of nodes that represent how they should be rendered –

- Block Nodes (analogous to HTML concept of Block-level elements) that are each rendered on a new line and occupy the available width. Block nodes could contain other block nodes or inline nodes inside them. An observation here is that the top-level nodes of a document would always be block nodes.

- Inline Nodes (analogous to HTML concept of Inline elements) that start rendering on the same line as the previous node. There are some differences in how inline elements are represented in different editing libraries. SlateJS allows for inline elements to be nodes themselves. DraftJS, another popular Rich Text Editing library, lets you use the concept of Entities to render inline elements. Links and Inline Images are examples of Inline nodes.

- Void Nodes — SlateJS also allows this third category of nodes that we will use later in this article to render media.

If you want to learn more about these categories, SlateJS’s documentation on Nodes is a good place to start.

Attributes

Similar to HTML’s concept of attributes, attributes in a Rich Text Document are used to represent non-content properties of a node or it’s children. For instance, a text node can have character-style attributes that tell us whether the text is bold/italic/underlined and so on. Although this article represents headings as nodes themselves, another way to represent them could be that nodes have paragraph-styles (paragraph & h1-h6) as attributes on them.

Below image gives an example of how a document’s structure (in JSON) is described at a more granular level using nodes and attributes highlighting some of the elements in the structure to the left.

Some of the things worth calling out here with the structure are:

- Text nodes are represented as

{text: 'text content'} - Properties of the nodes are stored directly on the node (e.g.

urlfor links andcaptionfor images) - SlateJS-specific representation of text attributes breaks the text nodes to be their own nodes if the character style changes. Hence, the text ‘Duis aute irure dolor’ is a text node of it’s own with

bold: trueset on it. Same is the case with the italic, underline and code style text in this document.

Locations And Selection

When building a rich text editor, it is crucial to have an understanding of how the most granular part of a document (say a character) can be represented with some sort of coordinates. This helps us navigate the document structure at runtime to understand where in the document hierarchy we are. Most importantly, location objects give us a way to represent user selection which is quite extensively used to tailor the user experience of the editor in real time. We will use selection to build our toolbar later in this article. Examples of these could be:

- Is the user’s cursor currently inside a link, maybe we should show them a menu to edit/remove the link?

- Has the user selected an image? Maybe we give them a menu to resize the image.

- If the user selects certain text and hits the DELETE button, we determine what user’s selected text was and remove that from the document.

SlateJS’s document on Location explains these data structures extensively but we go through them here quickly as we use these terms at different instances in the article and show an example in the diagram that follows.

- Path

Represented by an array of numbers, a path is the way to get to a node in the document. For instance, a path[2,3]represents the 3rd child node of the 2nd node in the document. - Point

More granular location of content represented by path + offset. For instance, a point of{path: [2,3], offset: 14}represents the 14th character of the 3rd child node inside the 2nd node of the document. - Range

A pair of points (calledanchorandfocus) that represent a range of text inside the document. This concept comes from Web’s Selection API whereanchoris where user’s selection began andfocusis where it ended. A collapsed range/selection denotes where anchor and focus points are the same (think of a blinking cursor in a text input for instance).

As an example let’s say that the user’s selection in our above document example is ipsum:

ipsum. (Large preview)The user’s selection can be represented as:

{ anchor: {path: [2,0], offset: 5}, /*0th text node inside the paragraph node which itself is index 2 in the document*/ focus: {path: [2,0], offset: 11}, // space + 'ipsum'

}`

Setting Up The Editor

In this section, we are going to set up the application and get a basic rich-text editor going with SlateJS. The boilerplate application would be create-react-appreact-bootstrap

Create a folder called wysiwyg-editor and run the below command from inside the directory to set up the react app. We then run a yarn start command that should spin up the local web server (port defaulting to 3000) and show you a React welcome screen.

npx create-react-app .

yarn start

We then move on to add the SlateJS dependencies to the application.

yarn add slate slate-react

slate is SlateJS’s core package and slate-react includes the set of React components we will use to render Slate editors. SlateJS exposes some more packages organized by functionality one might consider adding to their editor.

We first create a utils folder that holds any utility modules we create in this application. We start with creating an ExampleDocument.js that returns a basic document structure that contains a paragraph with some text. This module looks like below:

const ExampleDocument = [ { type: "paragraph", children: [ { text: "Hello World! This is my paragraph inside a sample document." }, ], },

]; export default ExampleDocument;

We now add a folder called components that will hold all our React components and do the following:

- Add our first React component

Editor.jsto it. It only returns adivfor now. - Update the

App.jscomponent to hold the document in its state which is initialized to ourExampleDocumentabove. - Render the Editor inside the app and pass the document state and an

onChangehandler down to the Editor so our document state is updated as the user updates it. - We use React bootstrap’s Nav components to add a navigation bar to the application as well.

App.js component now looks like below:

import Editor from './components/Editor'; function App() { const [document, updateDocument] = useState(ExampleDocument); return ( <> <Navbar bg="dark" variant="dark"> <Navbar.Brand href="#"> <img alt="" src="/app-icon.png" width="30" height="30" className="d-inline-block align-top" />{" "} WYSIWYG Editor </Navbar.Brand> </Navbar> <div className="App"> <Editor document={document} onChange={updateDocument} /> </div> </> );

Inside the Editor component, we then instantiate the SlateJS editor and hold it inside a useMemo so that the object doesn’t change in between re-renders.

// dependencies imported as below.

import { withReact } from "slate-react";

import { createEditor } from "slate"; const editor = useMemo(() => withReact(createEditor()), []);

createEditor gives us the SlateJS editor instance which we use extensively through the application to access selections, run data transformations and so on. withReact is a SlateJS plugin that adds React and DOM behaviors to the editor object. SlateJS Plugins are Javascript functions that receive the editor object and attach some configuration to it. This allows web developers to add configurations to their SlateJS editor instance in a composable way.

We now import and render <Slate /> and <Editable /> components from SlateJS with the document prop we get from App.js. Slate exposes a bunch of React contexts we use to access in the application code. Editable is the component that renders the document hierarchy for editing. Overall, the Editor.js

import { Editable, Slate, withReact } from "slate-react"; import { createEditor } from "slate";

import { useMemo } from "react"; export default function Editor({ document, onChange }) { const editor = useMemo(() => withReact(createEditor()), []); return ( <Slate editor={editor} value={document} onChange={onChange}> <Editable /> </Slate> );

}

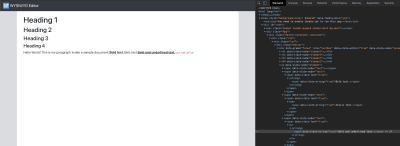

At this point, we have necessary React components added and the editor populated with an example document. Our Editor should be now set up allowing us to type in and change the content in real time — as in the screencast below.

Now, let’s move on to the next section where we configure the editor to render character styles and paragraph nodes.

CUSTOM TEXT RENDERING AND A TOOLBAR

Paragraph Style Nodes

Currently, our editor uses SlateJS’s default rendering for any new node types we may add to the document. In this section, we want to be able to render the heading nodes. To be able to do that, we provide a renderElement function prop to Slate’s components. This function gets called by Slate at runtime when it is trying to traverse the document tree and render each node. The renderElement function gets three parameters —

attributes

SlateJS specific that must need to be applied to the top-level DOM element being returned from this function.element

The node object itself as it exists in the document structurechildren

The children of this node as defined in the document structure.

We add our renderElement implementation to a hook called useEditorConfig where we will add more editor configurations as we go. We then use the hook on the editor instance inside Editor.js.

import { DefaultElement } from "slate-react"; export default function useEditorConfig(editor) { return { renderElement };

} function renderElement(props) { const { element, children, attributes } = props; switch (element.type) { case "paragraph": return <p {...attributes}>{children}</p>; case "h1": return <h1 {...attributes}>{children}</h1>; case "h2": return <h2 {...attributes}>{children}</h2>; case "h3": return <h3 {...attributes}>{children}</h3>; case "h4": return <h4 {...attributes}>{children}</h4>; default: // For the default case, we delegate to Slate's default rendering. return <DefaultElement {...props} />; }

}

Since this function gives us access to the element (which is the node itself), we can customize renderElement to implement a more customized rendering that does more than just checking element.type. For instance, you could have an image node that has a isInline property that we could use to return a different DOM structure that helps us render inline images as against block images.

We now update the Editor component to use this hook as below:

const { renderElement } = useEditorConfig(editor); return ( ... <Editable renderElement={renderElement} />

);

With the custom rendering in place, we update the ExampleDocument to include our new node types and verify that they render correctly inside the editor.

const ExampleDocument = [ { type: "h1", children: [{ text: "Heading 1" }], }, { type: "h2", children: [{ text: "Heading 2" }], }, // ...more heading nodes

Character Styles

Similar to renderElement, SlateJS gives out a function prop called renderLeaf that can be used to customize rendering of the text nodes (Leaf referring to text nodes which are the leaves/lowest level nodes of the document tree). Following the example of renderElement, we write an implementation for renderLeaf.

export default function useEditorConfig(editor) { return { renderElement, renderLeaf };

} // ...

function renderLeaf({ attributes, children, leaf }) { let el = <>{children}</>; if (leaf.bold) { el = <strong>{el}</strong>; } if (leaf.code) { el = <code>{el}</code>; } if (leaf.italic) { el = <em>{el}</em>; } if (leaf.underline) { el = <u>{el}</u>; } return <span {...attributes}>{el}</span>;

}

An important observation of the above implementation is that it allows us to respect HTML semantics for character styles. Since renderLeaf gives us access to the text node leaf itself, we can customize the function to implement a more customized rendering. For instance, you might have a way to let users choose a highlightColor for text and check that leaf property here to attach the respective styles.

We now update the Editor component to use the above, the ExampleDocument to have a few text nodes in the paragraph with combinations of these styles and verify that they are rendered as expected in the Editor with the semantic tags we used.

# src/components/Editor.js const { renderElement, renderLeaf } = useEditorConfig(editor); return ( ... <Editable renderElement={renderElement} renderLeaf={renderLeaf} />

);

# src/utils/ExampleDocument.js { type: "paragraph", children: [ { text: "Hello World! This is my paragraph inside a sample document." }, { text: "Bold text.", bold: true, code: true }, { text: "Italic text.", italic: true }, { text: "Bold and underlined text.", bold: true, underline: true }, { text: "variableFoo", code: true }, ], },

Adding A Toolbar

Let’s begin by adding a new component Toolbar.js to which we add a few buttons for character styles and a dropdown for paragraph styles and we wire these up later in the section.

const PARAGRAPH_STYLES = ["h1", "h2", "h3", "h4", "paragraph", "multiple"];

const CHARACTER_STYLES = ["bold", "italic", "underline", "code"]; export default function Toolbar({ selection, previousSelection }) { return ( <div className="toolbar"> {/* Dropdown for paragraph styles */} <DropdownButton className={"block-style-dropdown"} disabled={false} id="block-style" title={getLabelForBlockStyle("paragraph")} > {PARAGRAPH_STYLES.map((blockType) => ( <Dropdown.Item eventKey={blockType} key={blockType}> {getLabelForBlockStyle(blockType)} </Dropdown.Item> ))} </DropdownButton> {/* Buttons for character styles */} {CHARACTER_STYLES.map((style) => ( <ToolBarButton key={style} icon={<i className={`bi ${getIconForButton(style)}`} />} isActive={false} /> ))} </div> );

} function ToolBarButton(props) { const { icon, isActive, ...otherProps } = props; return ( <Button variant="outline-primary" className="toolbar-btn" active={isActive} {...otherProps} > {icon} </Button> );

}

We abstract away the buttons to the ToolbarButton component that is a wrapper around the React Bootstrap Button component. We then render the toolbar above the Editable inside Editor component and verify that the toolbar shows up in the application.

Here are the three key functionalities we need the toolbar to support:

- When the user’s cursor is in a certain spot in the document and they click one of the character style buttons, we need to toggle the style for the text they may type next.

- When the user selects a range of text and click one of the character style buttons, we need to toggle the style for that specific section.

- When the user selects a range of text, we want to update the paragraph-style dropdown to reflect the paragraph-type of the selection. If they do select a different value from the selection, we want to update the paragraph style of the entire selection to be what they selected.

Let’s look at how these functionalities work on the Editor before we start implementing them.

Listening To Selection

The most important thing the Toolbar needs to be able to perform the above functions is the Selection state of the document. As of writing this article, SlateJS does not expose a onSelectionChange method that could give us the latest selection state of the document. However, as selection changes in the editor, SlateJS does call the onChange method, even if the document contents haven’t changed. We use this as a way to be notified of selection change and store it in the Editor component’s state. We abstract this to a hook useSelection where we could do a more optimal update of the selection state. This is important as selection is a property that changes quite often for a WYSIWYG Editor instance.

import areEqual from "deep-equal"; export default function useSelection(editor) { const [selection, setSelection] = useState(editor.selection); const setSelectionOptimized = useCallback( (newSelection) => { // don't update the component state if selection hasn't changed. if (areEqual(selection, newSelection)) { return; } setSelection(newSelection); }, [setSelection, selection] ); return [selection, setSelectionOptimized];

}

We use this hook inside the Editor component as below and pass the selection to the Toolbar component.

const [selection, setSelection] = useSelection(editor); const onChangeHandler = useCallback( (document) => { onChange(document); setSelection(editor.selection); }, [editor.selection, onChange, setSelection] ); return ( <Slate editor={editor} value={document} onChange={onChangeHandler}> <Toolbar selection={selection} /> ...

Performance Consideration

In an application where we have a much bigger Editor codebase with a lot more functionalities, it is important to store and listen to selection changes in a performant way (like using some state management library) as components listening to selection changes are likely to render too often. One way to do this is to have optimized selectors on top of the Selection state that hold specific selection information. For instance, an editor might want to render an image resizing menu when an Image is selected. In such a case, it might be helpful to have a selector isImageSelected computed from the editor’s selection state and the Image menu would re-render only when this selector’s value changes. Redux’s Reselect is one such library that enables building selectors.

We don’t use selection inside the toolbar until later but passing it down as a prop makes the toolbar re-render each time the selection changes on the Editor. We do this because we cannot rely solely on the document content change to trigger a re-render on the hierarchy (App -> Editor -> Toolbar) as users might just keep clicking around the document thereby changing selection but never actually changing the document content itself.

Toggling Character Styles

We now move to getting what the active character styles are from SlateJS and using those inside the Editor. Let’s add a new JS module EditorUtils that will host all the util functions we build going forward to get/do stuff with SlateJS. Our first function in the module is getActiveStyles that gives a Set of active styles in the editor. We also add a function to toggle a style on the editor function — toggleStyle:

# src/utils/EditorUtils.js import { Editor } from "slate"; export function getActiveStyles(editor) { return new Set(Object.keys(Editor.marks(editor) ?? {}));

} export function toggleStyle(editor, style) { const activeStyles = getActiveStyles(editor); if (activeStyles.has(style)) { Editor.removeMark(editor, style); } else { Editor.addMark(editor, style, true); }

}

Both the functions take the editor object which is the Slate instance as a parameter as will a lot of util functions we add later in the article.In Slate terminology, formatting styles are called Marks and we use helper methods on Editor interface to get, add and remove these marks.We import these util functions inside the Toolbar and wire them to the buttons we added earlier.

# src/components/Toolbar.js import { getActiveStyles, toggleStyle } from "../utils/EditorUtils";

import { useEditor } from "slate-react"; export default function Toolbar({ selection }) { const editor = useEditor(); return <div

... {CHARACTER_STYLES.map((style) => ( <ToolBarButton key={style} characterStyle={style} icon={<i className={`bi ${getIconForButton(style)}`} />} isActive={getActiveStyles(editor).has(style)} onMouseDown={(event) => { event.preventDefault(); toggleStyle(editor, style); }} /> ))}

</div>

useEditor is a Slate hook that gives us access to the Slate instance from the context where it was attached by the <Slate> component higher up in the render hierarchy.

One might wonder why we use onMouseDown here instead of onClick? There is an open Github Issue about how Slate turns the selection to null when the editor loses focus in any way. So, if we attach onClick handlers to our toolbar buttons, the selection becomes null and users lose their cursor position trying to toggle a style which is not a great experience. We instead toggle the style by attaching a onMouseDown event which prevents the selection from getting reset. Another way to do this is to keep track of the selection ourselves so we know what the last selection was and use that to toggle the styles. We do introduce the concept of previousSelection later in the article but to solve a different problem.

SlateJS allows us to configure event handlers on the Editor. We use that to wire up keyboard shortcuts to toggle the character styles. To do that, we add a KeyBindings object inside useEditorConfig where we expose a onKeyDown event handler attached to the Editable component. We use the is-hotkey util to determine the key combination and toggle the corresponding style.

# src/hooks/useEditorConfig.js export default function useEditorConfig(editor) { const onKeyDown = useCallback( (event) => KeyBindings.onKeyDown(editor, event), [editor] ); return { renderElement, renderLeaf, onKeyDown };

} const KeyBindings = { onKeyDown: (editor, event) => { if (isHotkey("mod+b", event)) { toggleStyle(editor, "bold"); return; } if (isHotkey("mod+i", event)) { toggleStyle(editor, "italic"); return; } if (isHotkey("mod+c", event)) { toggleStyle(editor, "code"); return; } if (isHotkey("mod+u", event)) { toggleStyle(editor, "underline"); return; } },

}; # src/components/Editor.js

... <Editable renderElement={renderElement} renderLeaf={renderLeaf} onKeyDown={onKeyDown} />

Making Paragraph Style Dropdown Work

Let’s move on to making the Paragraph Styles dropdown work. Similar to how paragraph-style dropdowns work in popular Word Processing applications like MS Word or Google Docs, we want styles of the top level blocks in user’s selection to be reflected in the dropdown. If there is a single consistent style across the selection, we update the dropdown value to be that. If there are multiple of those, we set the dropdown value to be ‘Multiple’. This behavior must work for both — collapsed and expanded selections.

To implement this behavior, we need to be able to find the top-level blocks spanning the user’s selection. To do so, we use Slate’s Editor.nodes — A helper function commonly used to search for nodes in a tree filtered by different options.

nodes( editor: Editor, options?: { at?: Location | Span match?: NodeMatch<T> mode?: 'all' | 'highest' | 'lowest' universal?: boolean reverse?: boolean voids?: boolean } ) => Generator<NodeEntry<T>, void, undefined>

The helper function takes an Editor instance and an options object that is a way to filter nodes in the tree as it traverses it. The function returns a generator of NodeEntry. A NodeEntry in Slate terminology is a tuple of a node and the path to it — [node, pathToNode]. The options found here are available on most of the Slate helper functions. Let’s go through what each of those means:

at

This can be a Path/Point/Range that the helper function would use to scope down the tree traversal to. This defaults toeditor.selectionif not provided. We also use the default for our use case below as we’re interested in nodes within user’s selection.match

This is a matching function one can provide that is called on each node and included if it is a match. We use this parameter in our implementation below to filter to block elements only.mode

Let’s the helper functions know if we’re interested in all, highest-level or lowest level nodesatthe given location matchingmatchfunction. This parameter (set tohighest) helps us escape trying to traverse the tree up ourselves to find the top-level nodes.universal

Flag to choose between full or partial matches of the nodes. (GitHub Issue with the proposal for this flag has some examples explaining it)reverse

If the node search should be in the reverse direction of the start and end points of the location passed in.voids

If the search should filter to void elements only.

SlateJS exposes a lot of helper functions that let you query for nodes in different ways, traverse the tree, update the nodes or selections in complex ways. Worth digging into some of these interfaces (listed towards the end of this article) when building complex editing functionalities on top of Slate.

With that background on the helper function, below is an implementation of getTextBlockStyle.

# src/utils/EditorUtils.js export function getTextBlockStyle(editor) { const selection = editor.selection; if (selection == null) { return null; } const topLevelBlockNodesInSelection = Editor.nodes(editor, { at: editor.selection, mode: "highest", match: (n) => Editor.isBlock(editor, n), }); let blockType = null; let nodeEntry = topLevelBlockNodesInSelection.next(); while (!nodeEntry.done) { const [node, _] = nodeEntry.value; if (blockType == null) { blockType = node.type; } else if (blockType !== node.type) { return "multiple"; } nodeEntry = topLevelBlockNodesInSelection.next(); } return blockType;

}

Performance Consideration

The current implementation of Editor.nodes finds all the nodes throughout the tree across all levels that are within the range of the at param and then runs match filters on it (check nodeEntries and the filtering later — source). This is okay for smaller documents. However, for our use case, if the user selected, say 3 headings and 2 paragraphs (each paragraph containing say 10 text nodes), it will cycle through at least 25 nodes (3 + 2 + 2*10) and try to run filters on them. Since we already know we’re interested in top-level nodes only, we could find start and end indexes of the top level blocks from the selection and iterate ourselves. Such a logic would loop through only 3 node entries (2 headings and 1 paragraph). Code for that would look something like below:

export function getTextBlockStyle(editor) { const selection = editor.selection; if (selection == null) { return null; } // gives the forward-direction points in case the selection was // was backwards. const [start, end] = Range.edges(selection); //path[0] gives us the index of the top-level block. let startTopLevelBlockIndex = start.path[0]; const endTopLevelBlockIndex = end.path[0]; let blockType = null; while (startTopLevelBlockIndex = endTopLevelBlockIndex) { const [node, _] = Editor.node(editor, [startTopLevelBlockIndex]); if (blockType == null) { blockType = node.type; } else if (blockType !== node.type) { return "multiple"; } startTopLevelBlockIndex++; } return blockType;

}

As we add more functionalities to a WYSIWYG Editor and need to traverse the document tree often, it is important to think about the most performant ways to do so for the use case at hand as the available API or helper methods might not always be the most efficient way to do so.

Once we have getTextBlockStyle implemented, toggling of the block style is relatively straightforward. If the current style is not what user selected in the dropdown, we toggle the style to that. If it is already what user selected, we toggle it to be a paragraph. Because we are representing paragraph styles as nodes in our document structure, toggle a paragraph style essentially means changing the type property on the node. We use Transforms.setNodes provided by Slate to update properties on nodes.

Our toggleBlockType’s implementation is as below:

# src/utils/EditorUtils.js export function toggleBlockType(editor, blockType) { const currentBlockType = getTextBlockStyle(editor); const changeTo = currentBlockType === blockType ? "paragraph" : blockType; Transforms.setNodes( editor, { type: changeTo }, // Node filtering options supported here too. We use the same // we used with Editor.nodes above. { at: editor.selection, match: (n) => Editor.isBlock(editor, n) } );

}

Finally, we update our Paragraph-Style dropdown to use these utility functions.

#src/components/Toolbar.js const onBlockTypeChange = useCallback( (targetType) => { if (targetType === "multiple") { return; } toggleBlockType(editor, targetType); }, [editor] ); const blockType = getTextBlockStyle(editor); return ( <div className="toolbar"> <DropdownButton ..... disabled={blockType == null} title={getLabelForBlockStyle(blockType ?? "paragraph")} onSelect={onBlockTypeChange} > {PARAGRAPH_STYLES.map((blockType) => ( <Dropdown.Item eventKey={blockType} key={blockType}> {getLabelForBlockStyle(blockType)} </Dropdown.Item> ))} </DropdownButton>

....

);

LINKS

In this section, we are going to add support to show, add, remove and change links. We will also add a Link-Detector functionality — quite similar to how Google Docs or MS Word that scan the text typed by the user and checks if there are links in there. If there are, they are converted into link objects so that the user doesn’t have to use toolbar buttons to do that themselves.

Rendering Links

In our editor, we are going to implement links as inline nodes with SlateJS. We update our editor config to flag links as inline nodes for SlateJS and also provide a component to render so Slate knows how to render the link nodes.

# src/hooks/useEditorConfig.js

export default function useEditorConfig(editor) { ... editor.isInline = (element) => ["link"].includes(element.type); return {....}

} function renderElement(props) { const { element, children, attributes } = props; switch (element.type) { ... case "link": return <Link {...props} url={element.url} />; ... }

}

# src/components/Link.js

export default function Link({ element, attributes, children }) { return ( <a href={element.url} {...attributes} className={"link"}> {children} </a> );

}

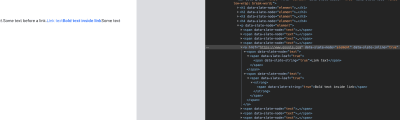

We then add a link node to our ExampleDocument and verify that it renders correctly (including a case for character styles inside a link) in the Editor.

# src/utils/ExampleDocument.js

{ type: "paragraph", children: [ ... { text: "Some text before a link." }, { type: "link", url: "https://www.google.com", children: [ { text: "Link text" }, { text: "Bold text inside link", bold: true }, ], }, ...

}

Adding A Link Button To The Toolbar

Let’s add a Link Button to the toolbar that enables the user to do the following:

- Selecting some text and clicking on the button converts that text into a link

- Having a blinking cursor (collapsed selection) and clicking the button inserts a new link there

- If the user’s selection is inside a link, clicking on the button should toggle the link — meaning convert the link back to text.

To build these functionalities, we need a way in the toolbar to know if the user’s selection is inside a link node. We add a util function that traverses the levels in upward direction from the user’s selection to find a link node if there is one, using Editor.above helper function from SlateJS.

# src/utils/EditorUtils.js export function isLinkNodeAtSelection(editor, selection) { if (selection == null) { return false; } return ( Editor.above(editor, { at: selection, match: (n) => n.type === "link", }) != null );

}

Now, let’s add a button to the toolbar that is in active state if the user’s selection is inside a link node.

# src/components/Toolbar.js return ( <div className="toolbar"> ... {/* Link Button */} <ToolBarButton isActive={isLinkNodeAtSelection(editor, editor.selection)} label={<i className={`bi ${getIconForButton("link")}`} />} /> </div> );

To toggle links in the editor, we add a util function toggleLinkAtSelection. Let’s first look at how the toggle works when you have some text selected. When the user selects some text and clicks on the button, we want only the selected text to become a link. What this inherently means is that we need to break the text node that contains selected text and extract the selected text into a new link node. The before and after states of these would look something like below:

If we had to do this by ourselves, we’d have to figure out the range of selection and create three new nodes (text, link, text) that replace the original text node. SlateJS has a helper function called Transforms.wrapNodes that does exactly this — wrap nodes at a location into a new container node. We also have a helper available for the reverse of this process — Transforms.unwrapNodes which we use to remove links from selected text and merge that text back into the text nodes around it. With that, toggleLinkAtSelection has the below implementation to insert a new link at an expanded selection.

# src/utils/EditorUtils.js export function toggleLinkAtSelection(editor) { if (!isLinkNodeAtSelection(editor, editor.selection)) { const isSelectionCollapsed = Range.isCollapsed(editor.selection); if (isSelectionCollapsed) { Transforms.insertNodes( editor, { type: "link", url: '#', children: [{ text: 'link' }], }, { at: editor.selection } ); } else { Transforms.wrapNodes( editor, { type: "link", url: '#', children: [{ text: '' }] }, { split: true, at: editor.selection } ); } } else { Transforms.unwrapNodes(editor, { match: (n) => Element.isElement(n) && n.type === "link", }); }

}

If the selection is collapsed, we insert a new node there with Transform.insertNodes

# src/components/Toolbar.js <ToolBarButton ... isActive={isLinkNodeAtSelection(editor, editor.selection)} onMouseDown={() => toggleLinkAtSelection(editor)} />

So far, our editor has a way to add and remove links but we don’t have a way to update the URLs associated with these links. How about we extend the user experience to allow users to edit it easily with a contextual menu? To enable link editing, we will build a link-editing popover that shows up whenever the user selection is inside a link and lets them edit and apply the URL to that link node. Let’s start with building an empty LinkEditor component and rendering it whenever the user selection is inside a link.

# src/components/LinkEditor.js

export default function LinkEditor() { return ( <Card className={"link-editor"}> <Card.Body></Card.Body> </Card> );

}

# src/components/Editor.js <div className="editor"> {isLinkNodeAtSelection(editor, selection) ? <LinkEditor /> : null} <Editable renderElement={renderElement} renderLeaf={renderLeaf} onKeyDown={onKeyDown} />

</div>

Since we are rendering the LinkEditor outside the editor, we need a way to tell LinkEditor where the link is located in the DOM tree so it could render itself near the editor. The way we do this is use Slate’s React API to find the DOM node corresponding to the link node in selection. And we then use getBoundingClientRect() to find the link’s DOM element’s bounds and the editor component’s bounds and compute the top and left for the link editor. The code updates to Editor and LinkEditor are as below —

# src/components/Editor.js const editorRef = useRef(null)

<div className="editor" ref={editorRef}> {isLinkNodeAtSelection(editor, selection) ? ( <LinkEditor editorOffsets={ editorRef.current != null ? { x: editorRef.current.getBoundingClientRect().x, y: editorRef.current.getBoundingClientRect().y, } : null } /> ) : null} <Editable renderElement={renderElement} ...

# src/components/LinkEditor.js import { ReactEditor } from "slate-react"; export default function LinkEditor({ editorOffsets }) { const linkEditorRef = useRef(null); const [linkNode, path] = Editor.above(editor, { match: (n) => n.type === "link", }); useEffect(() => { const linkEditorEl = linkEditorRef.current; if (linkEditorEl == null) { return; } const linkDOMNode = ReactEditor.toDOMNode(editor, linkNode); const { x: nodeX, height: nodeHeight, y: nodeY, } = linkDOMNode.getBoundingClientRect(); linkEditorEl.style.display = "block"; linkEditorEl.style.top = `${nodeY + nodeHeight — editorOffsets.y}px`; linkEditorEl.style.left = `${nodeX — editorOffsets.x}px`; }, [editor, editorOffsets.x, editorOffsets.y, node]); if (editorOffsets == null) { return null; } return <Card ref={linkEditorRef} className={"link-editor"}></Card>;

}

SlateJS internally maintains maps of nodes to their respective DOM elements. We access that map and find the link’s DOM element using ReactEditor.toDOMNode.

As seen in the video above, when a link is inserted and doesn’t have a URL, because the selection is inside the link, it opens the link editor thereby giving the user a way to type in a URL for the newly inserted link and hence closes the loop on the user experience there.

We now add an input element and a button to the LinkEditor that let the user type in a URL and apply it to the link node. We use the isUrl package for URL validation.

# src/components/LinkEditor.js import isUrl from "is-url"; export default function LinkEditor({ editorOffsets }) { const [linkURL, setLinkURL] = useState(linkNode.url); // update state if `linkNode` changes useEffect(() => { setLinkURL(linkNode.url); }, [linkNode]); const onLinkURLChange = useCallback( (event) => setLinkURL(event.target.value), [setLinkURL] ); const onApply = useCallback( (event) => { Transforms.setNodes(editor, { url: linkURL }, { at: path }); }, [editor, linkURL, path] ); return ( ... <Form.Control size="sm" type="text" value={linkURL} onChange={onLinkURLChange} /> <Button className={"link-editor-btn"} size="sm" variant="primary" disabled={!isUrl(linkURL)} onClick={onApply} > Apply </Button> ... );

With the form elements wired up, let’s see if the link editor works as expected.

As we see here in the video, when the user tries to click into the input, the link editor disappears. This is because as we render the link editor outside the Editable component, when the user clicks on the input element, SlateJS thinks the editor has lost focus and resets the selection to be null which removes the LinkEditor since isLinkActiveAtSelection is not true anymore. There is an open GitHub Issue that talks about this Slate behavior. One way to solve this is to track the previous selection of a user as it changes and when the editor does lose focus, we could look at the previous selection and still show a link editor menu if previous selection had a link in it. Let’s update the useSelection hook to remember the previous selection and return that to the Editor component.

# src/hooks/useSelection.js

export default function useSelection(editor) { const [selection, setSelection] = useState(editor.selection); const previousSelection = useRef(null); const setSelectionOptimized = useCallback( (newSelection) => { if (areEqual(selection, newSelection)) { return; } previousSelection.current = selection; setSelection(newSelection); }, [setSelection, selection] ); return [previousSelection.current, selection, setSelectionOptimized];

}

We then update the logic in the Editor component to show the link menu even if the previous selection had a link in it.

# src/components/Editor.js const [previousSelection, selection, setSelection] = useSelection(editor); let selectionForLink = null; if (isLinkNodeAtSelection(editor, selection)) { selectionForLink = selection; } else if (selection == null && isLinkNodeAtSelection(editor, previousSelection)) { selectionForLink = previousSelection; } return ( ... <div className="editor" ref={editorRef}> {selectionForLink != null ? ( <LinkEditor selectionForLink={selectionForLink} editorOffsets={..} ...

);

We then update LinkEditor to use selectionForLink to look up the link node, render below it and update it’s URL.

# src/components/Link.js

export default function LinkEditor({ editorOffsets, selectionForLink }) { ... const [node, path] = Editor.above(editor, { at: selectionForLink, match: (n) => n.type === "link", }); ...

Detecting Links In Text

Most of the word processing applications identify and convert links inside text to link objects. Let’s see how that would work in the editor before we start building it.

The steps of the logic to enable this behavior would be:

- As the document changes with the user typing, find the last character inserted by the user. If that character is a space, we know there must be a word that might have come before it.

- If the last character was space, we mark that as the end boundary of the word that came before it. We then traverse back character by character inside the text node to find where that word began. During this traversal, we have to be careful to not go past the edge of the start of the node into the previous node.

- Once we have found the start and end boundaries of the word before, we check the string of the word and see if that was a URL. If it was, we convert it into a link node.

Our logic lives in a util function identifyLinksInTextIfAny that lives in EditorUtils and is called inside the onChange in Editor component.

# src/components/Editor.js const onChangeHandler = useCallback( (document) => { ... identifyLinksInTextIfAny(editor); }, [editor, onChange, setSelection] );

Here is identifyLinksInTextIfAny with the logic for Step 1 implemented:

export function identifyLinksInTextIfAny(editor) { // if selection is not collapsed, we do not proceed with the link // detection if (editor.selection == null || !Range.isCollapsed(editor.selection)) { return; } const [node, _] = Editor.parent(editor, editor.selection); // if we are already inside a link, exit early. if (node.type === "link") { return; } const [currentNode, currentNodePath] = Editor.node(editor, editor.selection); // if we are not inside a text node, exit early. if (!Text.isText(currentNode)) { return; } let [start] = Range.edges(editor.selection); const cursorPoint = start; const startPointOfLastCharacter = Editor.before(editor, editor.selection, { unit: "character", }); const lastCharacter = Editor.string( editor, Editor.range(editor, startPointOfLastCharacter, cursorPoint) ); if(lastCharacter !== ' ') { return; }

There are two SlateJS helper functions which make things easy here.

Editor.before— Gives us the point before a certain location. It takesunitas a parameter so we could ask for the character/word/block etc before thelocationpassed in.Editor.string— Gets the string inside a range.

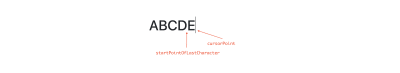

As an example, the diagram below explains what values of these variables are when the user inserts a character ‘E’ and their cursor is sitting after it.

cursorPoint and startPointOfLastCharacter after Step 1 with an example text. (Large preview)If the text ’ABCDE’ was the first text node of the first paragraph in the document, our point values would be —

cursorPoint = { path: [0,0], offset: 5}

startPointOfLastCharacter = { path: [0,0], offset: 4}

If the last character was a space, we know where it started — startPointOfLastCharacter.Let’s move to step-2 where we move backwards character-by-character until either we find another space or the start of the text node itself.

... if (lastCharacter !== " ") { return; } let end = startPointOfLastCharacter; start = Editor.before(editor, end, { unit: "character", }); const startOfTextNode = Editor.point(editor, currentNodePath, { edge: "start", }); while ( Editor.string(editor, Editor.range(editor, start, end)) !== " " && !Point.isBefore(start, startOfTextNode) ) { end = start; start = Editor.before(editor, end, { unit: "character" }); } const lastWordRange = Editor.range(editor, end, startPointOfLastCharacter); const lastWord = Editor.string(editor, lastWordRange);

Here is a diagram that shows where these different points point to once we find the last word entered to be ABCDE.

Note that start and end are the points before and after the space there. Similarly, startPointOfLastCharacter and cursorPoint are the points before and after the space user just inserted. Hence [end,startPointOfLastCharacter] gives us the last word inserted.

We log the value of lastWord to the console and verify the values as we type.

Now that we have deduced what the last word was that the user typed, we verify that it was a URL indeed and convert that range into a link object. This conversion looks similar to how the toolbar link button converted a user’s selected text into a link.

if (isUrl(lastWord)) { Promise.resolve().then(() => { Transforms.wrapNodes( editor, { type: "link", url: lastWord, children: [{ text: lastWord }] }, { split: true, at: lastWordRange } ); }); }

identifyLinksInTextIfAny is called inside Slate’s onChange so we wouldn’t want to update the document structure inside the onChange. Hence, we put this update on our task queue with a Promise.resolve().then(..) call.

Let’s see the logic come together in action! We verify if we insert links at the end, in the middle or the start of a text node.

With that, we have wrapped up functionalities for links on the editor and move on to Images.

Handling Images

In this section, we focus on adding support to render image nodes, add new images and update image captions. Images, in our document structure, would be represented as Void nodes. Void nodes in SlateJS (analogous to Void elements in HTML spec) are such that their contents are not editable text. That allows us to render images as voids. Because of Slate’s flexibility with rendering, we can still render our own editable elements inside Void elements — which we will for image caption-editing. SlateJS has an example which demonstrates how you can embed an entire Rich Text Editor inside a Void element.

To render images, we configure the editor to treat images as Void elements and provide a render implementation of how images should be rendered. We add an image to our ExampleDocument and verify that it renders correctly with the caption.

# src/hooks/useEditorConfig.js export default function useEditorConfig(editor) { const { isVoid } = editor; editor.isVoid = (element) => { return ["image"].includes(element.type) || isVoid(element); }; ...

} function renderElement(props) { const { element, children, attributes } = props; switch (element.type) { case "image": return <Image {...props} />;

...

`` ``

# src/components/Image.js

function Image({ attributes, children, element }) { return ( <div contentEditable={false} {...attributes}> <div className={classNames({ "image-container": true, })} > <img src={String(element.url)} alt={element.caption} className={"image"} /> <div className={"image-caption-read-mode"}>{element.caption}</div> </div> {children} </div> );

}

Two things to remember when trying to render void nodes with SlateJS:

- The root DOM element should have

contentEditable={false}set on it so that SlateJS treats its contents so. Without this, as you interact with the void element, SlateJS may try to compute selections etc. and break as a result. - Even if Void nodes don’t have any child nodes (like our image node as an example), we still need to render

childrenand provide an empty text node as child (seeExampleDocumentbelow) which is treated as a selection point of the Void element by SlateJS

We now update the ExampleDocument to add an image and verify that it shows up with the caption in the editor.

# src/utils/ExampleDocument.js const ExampleDocument = [ ... { type: "image", url: "/photos/puppy.jpg", caption: "Puppy", // empty text node as child for the Void element. children: [{ text: "" }], },

];

Now let’s focus on caption-editing. The way we want this to be a seamless experience for the user is that when they click on the caption, we show a text input where they can edit the caption. If they click outside the input or hit the RETURN key, we treat that as a confirmation to apply the caption. We then update the caption on the image node and switch the caption back to read mode. Let’s see it in action so we have an idea of what we’re building.

Let’s update our Image component to have a state for caption’s read-edit modes. We update the local caption state as the user updates it and when they click out (onBlur) or hit RETURN (onKeyDown), we apply the caption to the node and switch to read mode again.

const Image = ({ attributes, children, element }) => { const [isEditingCaption, setEditingCaption] = useState(false); const [caption, setCaption] = useState(element.caption); ... const applyCaptionChange = useCallback( (captionInput) => { const imageNodeEntry = Editor.above(editor, { match: (n) => n.type === "image", }); if (imageNodeEntry == null) { return; } if (captionInput != null) { setCaption(captionInput); } Transforms.setNodes( editor, { caption: captionInput }, { at: imageNodeEntry[1] } ); }, [editor, setCaption] ); const onCaptionChange = useCallback( (event) => { setCaption(event.target.value); }, [editor.selection, setCaption] ); const onKeyDown = useCallback( (event) => { if (!isHotkey("enter", event)) { return; } applyCaptionChange(event.target.value); setEditingCaption(false); }, [applyCaptionChange, setEditingCaption] ); const onToggleCaptionEditMode = useCallback( (event) => { const wasEditing = isEditingCaption; setEditingCaption(!isEditingCaption); wasEditing && applyCaptionChange(caption); }, [editor.selection, isEditingCaption, applyCaptionChange, caption] ); return ( ... {isEditingCaption ? ( <Form.Control autoFocus={true} className={"image-caption-input"} size="sm" type="text" defaultValue={element.caption} onKeyDown={onKeyDown} onChange={onCaptionChange} onBlur={onToggleCaptionEditMode} /> ) : ( <div className={"image-caption-read-mode"} onClick={onToggleCaptionEditMode} > {caption} </div> )} </div> ...

With that, the caption editing functionality is complete. We now move to adding a way for users to upload images to the editor. Let’s add a toolbar button that lets users select and upload an image.

# src/components/Toolbar.js const onImageSelected = useImageUploadHandler(editor, previousSelection); return ( <div className="toolbar"> .... <ToolBarButton isActive={false} as={"label"} htmlFor="image-upload" label={ <> <i className={`bi ${getIconForButton("image")}`} /> <input type="file" id="image-upload" className="image-upload-input" accept="image/png, image/jpeg" onChange={onImageSelected} /> </> } /> </div>

As we work with image uploads, the code could grow quite a bit so we move the image-upload handling to a hook useImageUploadHandler that gives out a callback attached to the file-input element. We’ll discuss shortly about why it needs the previousSelection state.

Before we implement useImageUploadHandler, we’ll set up the server to be able to upload an image to. We setup an Express server and install two other packages — cors and multer that handle file uploads for us.

yarn add express cors multer

We then add a src/server.js script that configures the Express server with cors and multer and exposes an endpoint /upload which we will upload the image to.

# src/server.js const storage = multer.diskStorage({ destination: function (req, file, cb) { cb(null, "./public/photos/"); }, filename: function (req, file, cb) { cb(null, file.originalname); },

}); var upload = multer({ storage: storage }).single("photo"); app.post("/upload", function (req, res) { upload(req, res, function (err) { if (err instanceof multer.MulterError) { return res.status(500).json(err); } else if (err) { return res.status(500).json(err); } return res.status(200).send(req.file); });

}); app.use(cors());

app.listen(port, () => console.log(`Listening on port ${port}`));

Now that we have the server setup, we can focus on handling the image upload. When the user uploads an image, it could be a few seconds before the image gets uploaded and we have a URL for it. However, we do what to give the user immediate feedback that the image upload is in progress so that they know the image is being inserted in the editor. Here are the steps we implement to make this behavior work –

- Once the user selects an image, we insert an image node at the user’s cursor position with a flag

isUploadingset on it so we can show the user a loading state. - We send the request to the server to upload the image.

- Once the request is complete and we have an image URL, we set that on the image and remove the loading state.

Let’s begin with the first step where we insert the image node. Now, the tricky part here is we run into the same issue with selection as with the link button in the toolbar. As soon as the user clicks on the Image button in the toolbar, the editor loses focus and the selection becomes null. If we try to insert an image, we don’t know where the user’s cursor was. Tracking previousSelection gives us that location and we use that to insert the node.

# src/hooks/useImageUploadHandler.js

import { v4 as uuidv4 } from "uuid"; export default function useImageUploadHandler(editor, previousSelection) { return useCallback( (event) => { event.preventDefault(); const files = event.target.files; if (files.length === 0) { return; } const file = files[0]; const fileName = file.name; const formData = new FormData(); formData.append("photo", file); const id = uuidv4(); Transforms.insertNodes( editor, { id, type: "image", caption: fileName, url: null, isUploading: true, children: [{ text: "" }], }, { at: previousSelection, select: true } ); }, [editor, previousSelection] );

}

As we insert the new image node, we also assign it an identifier id using the uuid package. We’ll discuss in Step (3)’s implementation why we need that. We now update the image component to use the isUploading flag to show a loading state.

{!element.isUploading && element.url != null ? ( <img src={element.url} alt={caption} className={"image"} />

) : ( <div className={"image-upload-placeholder"}> <Spinner animation="border" variant="dark" /> </div>

)}

That completes the implementation of step 1. Let’s verify that we are able to select an image to upload, see the image node getting inserted with a loading indicator where it was inserted in the document.

Moving to Step (2), we will use axois library to send a request to the server.

export default function useImageUploadHandler(editor, previousSelection) { return useCallback((event) => { .... Transforms.insertNodes( … {at: previousSelection, select: true} ); axios .post("/upload", formData, { headers: { "content-type": "multipart/form-data", }, }) .then((response) => { // update the image node. }) .catch((error) => { // Fire another Transform.setNodes to set an upload failed state on the image }); }, [...]);

}

We verify that the image upload works and the image does show up in the public/photos folder of the app. Now that the image upload is complete, we move to Step (3) where we want to set the URL on the image in the resolve() function of the axios promise. We could update the image with Transforms.setNodes but we have a problem — we do not have the path to the newly inserted image node. Let’s see what our options are to get to that image —

- Can’t we use

editor.selectionas the selection must be on the newly inserted image node? We cannot guarantee this since while the image was uploading, the user might have clicked somewhere else and the selection might have changed. - How about using

previousSelectionwhich we used to insert the image node in the first place? For the same reason we can’t useeditor.selection, we can’t usepreviousSelectionsince it may have changed too. - SlateJS has a History module that tracks all the changes happening to the document. We could use this module to search the history and find the last inserted image node. This also isn’t completely reliable if it took longer for the image to upload and the user inserted more images in different parts of the document before the first upload completed.

- Currently,

Transform.insertNodes’s API doesn’t return any information about the inserted nodes. If it could return the paths to the inserted nodes, we could use that to find the precise image node we should update.

Since none of the above approaches work, we apply an id to the inserted image node (in Step (1)) and use the same id again to locate it when the image upload is complete. With that, our code for Step (3) looks like below —

axios .post("/upload", formData, { headers: { "content-type": "multipart/form-data", }, }) .then((response) => { const newImageEntry = Editor.nodes(editor, { match: (n) => n.id === id, }); if (newImageEntry == null) { return; } Transforms.setNodes( editor, { isUploading: false, url: `/photos/${fileName}` }, { at: newImageEntry[1] } ); }) .catch((error) => { // Fire another Transform.setNodes to set an upload failure state // on the image. });

With the implementation of all three steps complete, we are ready to test the image upload end to end.

With that, we’ve wrapped up Images for our editor. Currently, we show a loading state of the same size irrespective of the image. This could be a jarring experience for the user if the loading state is replaced by a drastically smaller or bigger image when the upload completes. A good follow up to the upload experience is getting the image dimensions before the upload and showing a placeholder of that size so that transition is seamless. The hook we add above could be extended to support other media types like video or documents and render those types of nodes as well.

Conclusion

In this article, we have built a WYSIWYG Editor that has a basic set of functionalities and some micro user-experiences like link detection, in-place link editing and image caption editing that helped us go deeper with SlateJS and concepts of Rich Text Editing in general. If this problem space surrounding Rich Text Editing or Word Processing interests you, some of the cool problems to go after could be:

- Collaboration

- A richer text editing experience that supports text alignments, inline images, copy-paste, changing font and text colors etc.

- Importing from popular formats like Word documents and Markdown.

If you want to learn more SlateJS, here are some links that might be helpful.

- SlateJS Examples

A lot of examples that go beyond the basics and build functionalities that are usually found in Editors like Search & Highlight, Markdown Preview and Mentions. - API Docs

Reference to a lot of helper functions exposed by SlateJS that one might want to keep handy when trying to perform complex queries/transformations on SlateJS objects.

Lastly, SlateJS’s Slack Channel is a very active community of web developers building Rich Text Editing applications using SlateJS and a great place to learn more about the library and get help if needed.

(vf, il)