In this article, Ken Harker explains what third-party resource requests really are and which common optimization strategies can help reduce the impact on the user experience. By carefully considering how third-party requests will fit into your website during the design stage, you’ll be able to avoid the most significant negative impacts.

You’ve spent months putting together a great website design, crowd-pleasing content, and a business plan to bring it all together. You’ve focused on making the web design responsive to ensure that the widest audience of visitors can access your content. You’ve agonized over design patterns and usability. You’ve tested and retested the site for errors. Your operations team is ready to go. In short, you’ve done your due diligence in the areas of site design and delivery that you directly control. You’ve thought of everything… or have you?

Your website may be using more third-party services than you realize. These services use requests to external hosts (not servers you control) to deliver JavaScript framework libraries, custom fonts, advertising content, marketing analytics trackers, and more.

You may have a lean, agile, responsive site design only to find it gradually loaded down with more and more “extras” that are often put onto the site by marketing departments or business leaders who are not always thinking about website performance. You cannot always anticipate what you cannot control.

There are two big questions:

- How do you quantify the impact that these third-party requests have on website performance?

- How do you manage or even mitigate that impact?

Even if you cannot prevent all third-party requests, web designers can make choices that will have an impact. In this article, we will review what third-party resource requests are, consider how impactful they can be to the user experience, and discuss common optimization strategies to reduce the impact on the user experience. By carefully considering how third-party requests will fit into your website during the design stage, you can avoid the most significant negative impacts.

What Are Third-Party Services?

In order to understand third-party services, it may be easier to start with your own website content. Any resource (HTML, CSS, JavaScript, image, font, etc.) that you host and serve from your own domain(s) is called a “first-party” resource. You have control over what these resources are. All other requests that happen when visitors load your pages can be attributed to other parties.

Every major website on the Internet today relies — to some degree — on third-party services. The third-party in this case is someone (usually another commercial enterprise) other than you and your site visitors. In this case, we are not going to be talking about infrastructure services, such as a cloud computing platform like Microsoft Azure or a content distribution network like Akamai. Many websites use these services to deploy and run their businesses and understanding how they impact the user experience is important.

In this article, however, we are going to focus on the third-party services that work their way into the design of your web pages. These third-party resource requests load in your visitor’s browser while your web page is loading, even if your visitors don’t realize it. They may be critical to site functionality, or they have been added as an afterthought, but all of them can potentially affect how fast users perceive your page load times.

The HTTP Archive tracks third-party usage across a large swath of all active websites on the Internet today. According to the Third Parties chapter of their 2021 Web Almanac report, “a staggering 94.4% of mobile sites and 94.1% of desktop sites use at least one third-party resource.” They also found out that “45.9% of requests on mobile and 45.1% of requests on desktop are third-party requests.”

As it was noted in the report, third-party services share a few characteristics, such as:

- hosted on a shared and public origin,

- widely used by a variety of sites,

- uninfluenced by an individual site owner.

In other words, third-party services on your site are outsourced and operated by another party other than you. You have no direct control over where and how the requests are being hosted online. Many other websites may be using the same service, and the company that provides it must balance how to run their services to benefit all of their customers, not just you.

The upside to using third-party services on your site is that you do not need to develop everything you want to do yourself. In many cases, they can be super convenient to add or remove without having to push code changes to the site. The downside is that third-party requests can impact website visitors. Pages loaded up with dozens or hundreds of third-party calls can take longer to render or longer to become interactive.

What About Fourth-party Or Second-Party Services?

While the earliest, simplest third-party services were simple 1×1 pixel images used for tracking visitors, almost all third-party requests today load JavaScript into the browser. And JavaScript can certainly make requests for additional network resources. If these follow-on requests are to a different host or service, you might think of them as “fourth-party services”. If the fourth-party service, in turn, makes a request to yet another domain, then you get “fifth-party service” requests, and so forth. Technically, all of them might be “third parties” in the sense that they are neither you (the “first party”) nor your site visitor (the “second party”), but I think it helps to understand that these services are even more removed from your direct control than the ones you work directly with.

The most common scenario I see where fourth-party requests come into play is in advertising services. If you serve ads on your website through an ad broker, you may not even know what service will finally deliver the ad image that gets displayed in the browser.

Feeling like this is a little bit out of control? There’s at least one other way that resource requests you have no direct control over can impact your visitors’ experience. Sometimes, the visitor’s browser itself can be the origin of network activity.

For example, users can install browser plugins to suggest coupon codes when they are shopping, to scan web pages for malware, to play games or message friends, or do any number of other things. These plugins can fire off “second-party” requests in the middle of your page load, and there is nothing you can do about it. Unlike third-party services, the best you can do is be aware of what these second-party services are, so you know what to ignore when troubleshooting problems.

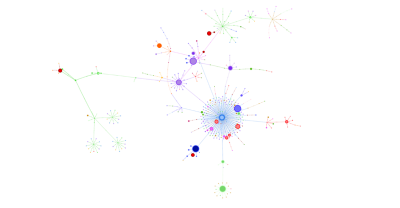

Create Your Own Request Map

As a discovery tool, request maps are great for identifying the source of third-party, fourth-party, fifth-party, etc., requests. They can also highlight very long redirection chains in your third-party traffic. Simon Hearne, an independent web performance consultant and one of the co-organizers of the London Web Performance Group, maintains an online Request Map tool that uses WebPageTest to get the data and Ghostery to visualize it.

Ad Blockers Makes Sites Faster

In addition to the browser plugins mentioned above, users love to install ad blockers. While many are motivated simply by a desire to see fewer ads, ad blockers also often make web pages load faster. Maciej Kocemba published research findings from Opera that showed that a typical website with ads could be rendered 51% faster if the ads were blocked.

This is obviously a concern for any website owner that monetizes page impressions with ads. They may not realize it, but users may be motivated to block ads partly to deal with slow third-party and fourth-party resource requests that lead to frustrating experiences. Faster page loads may reduce the motivation to use ad blockers.

The Revenue Trade-off You Need To Think About

Poor performance of third-party services can have other business impacts even if your website does not use advertising. Researchers and major companies have been publishing case studies for years, proving that slower page load experiences impact business metrics, including conversion rate, revenue, bounce rate, and more.

No matter how valuable you think a particular third-party service is to your business, that benefit needs to be compared to the cost of lost visitor engagement. Can a fancy third-party custom font give your site a new look and feel? Yes. Will the conversion rate or session length go down slightly as users see slower page loads? Or will visitors find the new look and feel worth the wait?

How To Identify Problematic Third-Party Services On Your Website

If you are like most websites, about half of the resource requests that load in your customers’ browsers — when they load a page from your website — are third-party requests. Identifying them should be straightforward.

Measuring Performance Impact

To quantify the performance impact of third-party resource requests on the user experience, we need to start by measuring page load performance. Many web performance measurement tools can measure the network load times of individual resource requests, and others can measure the client-side impacts of JavaScript resource requests. You may find that no single tool will answer every performance question you have about third parties. These tools fall into several categories.

Some tools that can be helpful in evaluating the impact of third-party resource requests are what you might describe as auditing tools. The most popular, by far, is the Google Lighthouse report (available in Chrome Developer Tools) and Google’s Page Speed Insights. These tools generally work with data from a single page load but go into some greater depth on impact than the tools designed for ongoing monitoring.

Synthetic web performance measurements use scripts to visit one or more pages on your website from one or more probe locations. Much like a laboratory environment (and depending to some degree on the features offered by the particular tool), you have control over the variables of the measurement. You can adjust what browser is used, the kind of network connection to employ, the locations to test from, whether or not the browser’s cache is empty or full, how frequently to take the measurements, and more.

Because most of the variables remain fixed from one test run to the next, synthetic measurements are great for measuring the impact of change but less capable of accurately or comprehensively identifying real visitor experience. They are more of a benchmark than a true measurement of real user experience. Some of the popular synthetic measurement tools are WebPageTest, SiteSpeed.io, Splunk Synthetic Monitoring, and Dynatrace.

For a more comprehensive measurement of visitor experience, you need Real User Measurements (RUM). RUM systems embed a small JavaScript payload onto every page of your site. The code interacts with industry-standard APIs implemented by modern browsers to collect performance data, augments it with additional custom data collection, and transmits this very high-resolution data about the page as a whole and every resource request.

The data may have some limitations, though — the only data that can be collected is what the APIs support, and Cross Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) restrictions in the browsers limit some details, especially around third-party resource requests. Some of the more popular RUM services are offered by Akamai, New Relic, Dynatrace, and AppDynamics.

What To Measure

Third-party resource requests can impact the user experience in several different ways, depending on whether they load early in the page load process or after the page is mostly complete. The risk you should be looking for with the measurement data you are collecting include:

- Delaying initial render

Resources that load prior to the initial page render (or First Contentful Paint) can be the most impactful overall. Many studies have shown that site visitors are more sensitive to delays at this point in the page load experience than any point after some visual progress has been achieved. Look for third-party requests that force new DNS lookups, require establishing connections to new origins, introduce redirection chains, include substantial client-side processing delay, or take a long time to download. - Other blocking effects

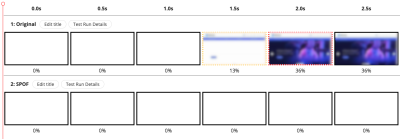

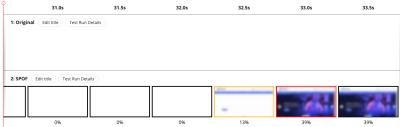

Any JavaScript resource that blocks other resources from being requested until its processing is completed is a concern. A third-party font request could cause render-blocking. Look for third-party JavaScript resources that block other JavaScript resources that are not being loaded asynchronously from being requested in a timely manner. Avoid third-party requests that introduce contention for scarce resources like bandwidth or CPU utilization. If a third-party resource request is blocking, consider alternatives or approaches to mitigate the risk if the third party is slower than normal or fails. - Single Points of Failure (SPOFs)

A resource request can be considered a SPOF if the web page fails to load or the load time is disastrously longer should the resource itself fail to load. For example, if a third-party host is down and your request takes 60 seconds to time out, if the initial render of the page is delayed 60 seconds as a result, then this is a SPOF.

Testing The Impact Of Specific Requests

Once you have identified potentially impactful third-party resource requests, measuring the specific performance impact of those requests can be challenging. Trying to separate the impact of a single request from all the others can be akin to trying to break down an alloy into its constituent metals because third-party requests are often made in parallel with first-party requests or third-party requests to other hosts, and they are competing with each other for the limited network, CPU, and memory resources of the client. Even with highly-detailed RUM or synthetic measurement data, it may not be practical.

The best way to approach the problem is through applied testing. Specifically, deliver pages with the third-party request or service as normal, and compare the performance to pages delivered without that particular third-party service but which are otherwise identical.

This is easiest to do with synthetic measurement tools. You can blackhole a particular domain so that the synthetic browser will never make the requests in the first place, simulating a page loading without that service on it. This can inform you about the performance (load times) impact of that third-party service. WebPageTest — a free synthetic measurement service (see the following three figures below for an example) — makes this easy.

A more sophisticated approach is to perform multivariate testing on your production site. In a multivariate test, you serve a version of the page with the third-party tag on it to one segment of your visitor population, and the other segment gets a version of the page without the third-party tag.

By using RUM tools, you can directly measure the real-world performance differences between the two test segments as well as the effects on business metrics (such as bounce rate, conversion or session length). Managing multivariate testing is a significant undertaking, but it can pay off in the long run.

Design Optimizations

Once you have a baseline of your site performance and some tools to test the basic performance impact of key third-party resource requests, it is time to implement some strategies to mitigate the impact that third-party services can have on performance.

Consider Removing Unneeded Services

By far, the most impactful change you can make is to remove any obsolete, unused, or unnecessary third-party tags from your site. After all, no resource loads faster than not making a resource request at all. Ironically, this may also be the most challenging optimization to put into practice. In many organizations, third-party tags or services “belong” to a variety of stakeholders, and finding a way to manage them is as much a cultural challenge as a technical one. Some basic steps to take include:

- Audit all third-party requests appearing on your pages on a periodic basis (for example, quarterly).

To make sure you capture all third-party requests, use a RUM service that collects data about every page view. If a third-party domain is showing up in more than a small fraction of page views and you do not already know what it is, find out immediately. New third-party tags may have been added by some stakeholders within your organization, or you may be finding a fourth-party tag because a third-party service changed its behavior. Either way, you need to understand what the third-party tags are and who in your organization is using them. - Keep records on third-party services.

Specifically, you want to know who the internal stakeholder is that “owns” that service and how it gets on the site. Is it hard-coded into the page HTML source? Is there JavaScript injected on the page by a CDN configuration? Are you using one (or more than one) tag manager? When does the contract with that service expire? The important thing is to have all the information on hand to know how to suspend or remove every third-party service if it becomes a performance issue or suddenly stops working, and who in your organization that is going to need to know. - Consider a periodic stakeholders meeting that includes a discussion of all third-party services to review the cost/benefit they introduce to the business. Even if it is still under contract, consider removing third-party services that stakeholders no longer use.

Geographically Align Your Third-Party Services With Your Visitors

If most of your visitors are in Europe, but a third-party service you are using is serving its resource content from the United States, those requests will likely have very slow load times as the traffic must cross an ocean each way. Some third-party services use a CDN of their own to ensure that they are serving requests from locations close to your visitors, but not all will do so. You may need to ensure that you are using appropriate hostnames or parameters in your requests. CDN Finder is a convenient tool to investigate which CDNs (if any) a third-party tag is using.

Loading Scripts Asynchronously

Blocking other resource requests from being made by the browser (often called “parser blocking”) is one of the most impactful (in a negative way) things a third-party resource can do. Historically, browsers have blocked while loading scripts to ensure that the page load experience is predictable. If scripts always load and evaluate in the same order, there are no surprises. The downside to this is that it takes longer to load the page.

Fortunately, identifying and blocking third-party script resources is relatively easy. Both WebPageTest and PageSpeed Insights (free-to-use tools) highlight resource requests that block other resource requests from being made. These tools work on one page (URL) at a time, so you will need to use them on a representative set of URLs to pick up all the blocking tags on your site.

Depending on how the third-party tag gets onto the page, you may be able to change a blocking script into a non-blocking script. Modern browsers support attributes to the script tag that gives the browser flexibility to load resources in a non-blocking manner. These are your basic options:

<script>

Without an additional attribute, many browsers will block the loading of subsequent scripts until after the script in question is loaded and evaluated. With third-party scripts, this is not only a performance concern but also a potential for a single point of failure (SPOF).<script async>

With async, the browser can download the script resource in parallel with other HTML parsing and downloading activity, but it will evaluate the JavaScript immediately once it is done downloading and pause HTML parsing while the script evaluation happens. If the script evaluation needs to happen early in the page load, this is the best choice.<script defer>

With defer, the script load will happen in parallel with HTML parsing and the fetching of other resources, and the script will only be evaluated after the HTML is fully parsed. This is the best choice for any third-party tag whose evaluation is less important than a fast render experience for your visitor.

Cascading StyleSheets

Another kind of blocking that can be impactful to the user experience is render-blocking. Cascading StyleSheets almost always block page render while they are being downloaded and evaluated because the browsers do not want to render content on the screen only to have to change how it looks partway through the page load. For this reason, best practice advice is to load CSS resources as early as you can in the page load, so the browser has all the information to render the page as soon as possible.

Third-party CSS requests are uncommon (mostly limited to custom font support), but if for some reason they are part of your site design, consider loading them directly through script tags in the base page HTML or through your CDN. Using a tag manager will just introduce additional delay in getting a critical resource into the browser as quickly as possible.

Some Further Thoughts On Fonts

Like CSS, custom fonts are also render-blocking. Fonts can radically change the visual appearance of text, so browsers do not want to render text on the screen only to have a visually disruptive change mid-page load. Unlike CSS, I see far more sites using third-party resources for their custom fonts, with Google Fonts and Adobe Typekit being the most popular.

Some implementations of custom fonts also involve loading third-party CSS, which introduces additional render-blocking. The resource requests for these fonts (.woff, woff2, or .ttf files, usually) are also not always done early in the page load. This is a problem for performance and a potential single point of failure.

Here are some ideas for managing third-party custom fonts on your site:

- Give serious consideration to whether you need custom fonts at all.

Page load times will be faster without them, and if the custom font is almost visually identical to some of the fantastic pre-installed system fonts now available in modern browsers, the brand impression benefit may be outweighed by the cost of slightly slower page loads frustrating your visitors. - If custom fonts are a requirement, consider how to deliver them as first-party resources.

You may be limited by font licensing restrictions in this respect, and serving fonts from your own domains will result in delivering more bytes to visitors from your CDN or ISP, which can increase costs. On the other hand, you no longer have a SPOF vulnerability, you gain control over caching headers, and your visitors can avoid making connections to yet another third-party host and all the delays that it introduces. - If you cannot avoid having third-party fonts on your site, consider using font-display properties in your CSS.

Setting the font-display property to swap (instead of block), for example, allows the browser to use system fonts until the custom fonts can be swapped in. If the visual change of the custom font is not too disruptive, this could be the best choice to give your visitors the content as early as possible while giving them the brand experience when the fonts do load. The fallback value is another choice that can incorporate a shorter blocking period and otherwise before behaving as a swap. The CSS-Tricks website has good documentation on font-display.

Two Script Management Solutions

One interesting approach to managing the performance impact of third parties is to move as many of them as possible to load via Web Workers. The core idea is to reserve the main thread in the browser for your first-party core scripts and let the browser manage and optimize your resource-intensive third-party scripts using Web Workers. Doing this is not trivial since Web Workers are limited to asynchronous communications with the main thread and many third-party scripts except synchronous access to browser resources, such as documents and windows.

A new open-source project called Partytown provides a library that implements a communications layer to make this work. It is still in the early stages of development, and you would want to test extensively for potential weird side effects. It might also not work well with a tag manager system if that’s a part of your architecture.

Akamai Script Management is a solution that uses Service Workers. This service essentially acts as a proxy inside the browser that has knowledge about the third-party services on the site and a policy about how to handle specific third-party requests. The policy can block requests for specific third parties, defer their request to later in the page load, or change the waiting time before throwing a timeout error for a request. If a third-party request is render blocking but that third-party service is down, for example, Script Management can mitigate the impact by reducing the length of time that the browser waits before deciding that the response is never going to arrive.

Conclusion

Third-party resource requests have become an integral part of the web. These services can provide value to your business, but they do come at a potential cost to the user experience.

A great way to start managing the impacts of third-party requests on your site’s user experience is to audit your site to see which and how many third-party domains and requests are being used. Next, use performance measurement tools to identify those that have the potential to degrade the user experience through render-blocking, resource contention, or single points of failure.

As you apply changes to mitigate the impact of third parties, develop a plan to use ongoing testing (such as Real User Measurement Services) to keep on top of site changes and unexpected changes to your third-party services.

By carefully considering how third-party requests will fit into your site during the design stage, you can avoid the most significant negative impacts. With ongoing performance monitoring, you can ensure that new problems with third-party requests are identified early. Don’t sink your website with third parties!

(yk, il)