Product ratings and reviews should provide clarity about a product’s qualities. Unfortunately, the nearly ubiquitous star rating scale can foster assumptions; it often lacks clearly defined measurements and fails to encourage written reviews. Context is important, and in this article, we will discuss a solution to improve communication among readers for finding and sharing literature.

The Setting: Ratings And Reviews

There is no shortage of articles criticizing star ratings. Many, myself included, have considered reimagining the ubiquitous star rating system. I might have continued ignoring those thoughts, disregarding the inconsistent and often bewildering star ratings that I encountered on apps until my frustrations mounted with Goodreads.

I love literature, and I believe it deserves better than a grading scale that elicits confusion and degrades communication among readers. In this article, we’ll imagine a better one to practice thinking and building more satisfying experiences.

The Inciting Incident: User Dissonance

The rating and review that inspired me to dig deeper into the star rating system can be paraphrased like this:

“The author’s writing is lyrical, and the story is lovely and haunting. However, this is not a genre I typically enjoy. Three stars.”

My brain stuttered when I read this comment. Had I written the review, even if I preferred other genres, I would have rated the book five stars. I expected anyone who said a book was lyrical, lovely, and haunting would feel the same; I expected that the original reviewer and I would share an understanding of what makes a book three stars versus five stars. The rating seemed at odds with the review, and I kept wondering how the original reviewer and I could be on such different pages.

Rising Action: Surmounting Problems

The reason users can have different definitions of star ratings is that the current rating system affords individual interpretations. The system inherently lacks clarity because it is based on glyphs, pictures representing words and ideas, but representations require interpretations. These idiosyncratic definitions can vary based on how someone’s experiences tell them to decipher a depiction — as shown in the aforementioned rating example, as mentioned by the Nielsen Norman Group, or as seen in the clown face emoji.

In an attempt to prevent individual interpretations, many companies uniquely define what each star category means on their sites. However, with a widely used glyph scale, this puts an unreasonable onus on users to learn the differences between every site to ensure correct usage—the equivalent of learning a homonym with hundreds of definitions. As there are few reasons to think one five-star scale broadly differs from another, companies reusing the system should anticipate that:

- Individuals have acquired their own understanding of the scale;

- Individuals will use their loose translation of the scale across the web.

Unfortunately, this creates countless little inconsistencies among user ratings that add up.

You can notice some of these inconsistencies if you scroll through ratings and reviews on a site like Goodreads, where there are a variety of interpretations of each star category. For instance:

- One-star reviews ranging from DNF (Did Not Finish) to extortion scams;

- Two-stars reviews ranging from unwilling to read more of the author’s work to being okay;

- Three-star reviews ranging from a genre not typically enjoyed to being recommendation worthy.

The only way to understand the intention behind most ratings is to read a corresponding review, which brings another problem to light. After gathering and averaging data from a mix of 100 popular classic and modern books on Goodreads — 50 of these are based on their most reviewed from the past five years — I learned that less than 5% of people who give a star rating write a review. We have to guess what the rest mean.

The inherent impreciseness and guesswork attributed to the system can hinder the overall goal of people using a social literature app. That goal can be summarized from Goodreads’ own mission statement:

“For readers to find and share books that they can fall in love with.”

Without speaking a common language through standardized rating definitions, readers relying on one another to discuss and discover meaningful literature becomes exceedingly difficult.

Additional Rising Action: Counter Arguments

However, let’s pretend everyone using a site like Goodreads agrees on what each star category means. The problem remains that a rating still tells us nothing about what a reader liked or disliked. Without personalized context, well-defined star ratings mainly act as a filtering system. People can choose to disregard books below a specific number of stars, but even they need to learn more about the books within their read-worthy range to decide what to read. On a social literature site, users should be able to depend on others for insight.

You might argue that algorithms can learn what everyone’s ratings mean and dispense recommendations. Let’s ignore the red flags from Goodreads oddly suggesting that I read a collected speech about compassion and a biography about The Who’s bassist, because I read a superhero novel, and let’s agree that this could work. People do trust algorithms more these days to accomplish tasks, but there is a tradeoff: socialization declines. If you overemphasize a machine finding and sharing books, users have fewer reasons to interact to achieve that goal as well. That is counterproductive to creating a social literature site.

In a world where quarantines are easily imagined possibilities and remote work spreads, the social aspect is becoming increasingly important. Studies show us that connection between people is more of a basic need than previously thought, and the improvements mentioned in this article will keep human interaction in mind.

The Climax: A Contextual Solution In Three Parts

What follows is one solution, among many, that addresses the aforementioned issues by observing three guiding principles:

- Building trust,

- Respecting time,

- Creating clarity.

The focus will be on a social literature app, but you can imagine some of these concepts applied anywhere star ratings are used. Let’s discuss each part of the solution.

Part One: Building Trust

The first piece of our solution primarily centers on trust, although it is not novel: readers are required to “Shelve” a book as “Read” before writing a review.

This feature is a step toward assuring readers that reviews are genuine. It also builds reviewers’ confidence that they will contribute to a credible conversation. Although users can lie to bypass the gate, honesty has more incentives on an app to find and share literature. A liar has little use for the former, and for the latter, if their intent is to gain attention for a book, they risk getting caught in a discussion that uncovers them, per the upcoming suggestions.

Part Two: Respecting Time and Creating Clarity

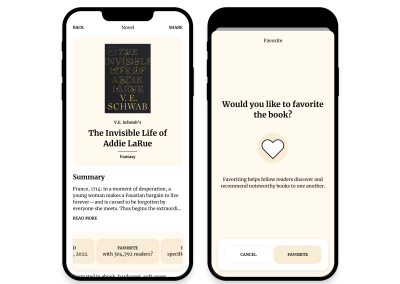

Simple and familiar, being mindful of people’s time, and contributing to clearness: once a reader shelves a book as “Read,” they can “Favorite” it.

Because this is a straightforward input, it requires less effort than deciphering the differences within anyone’s five-point star scale. Not favoriting a book does not indicate that you disliked it, and that is not the purpose. Favoriting tells people this is a noteworthy book for you, which may inspire them to learn why, read reviews, and interact with others. The number of times a book is favorited can be tallied to rank it in lists and garner extra attention.

In addition, vastly improving on our principle of clarity, once readers shelve a book as “Read,” the app also prompts them to mention what they enjoyed.

Respecting a reader’s time and developing a common language for users, the prompt provides a list of predefined answers to choose from. The options are mostly based on conventional literary characteristics, such as “Fast-paced plot,” “Lyrical language,” “Quirky characters,” and dozens of others.

Every quality a reader chooses gets added to traits others have chosen. On a book’s overview page, the selected qualities are ranked in descending order, equipping prospective readers with a clearer sense of if they might like a text based on top traits. The number of qualities a reviewer can choose is limited to encourage thoughtful selections and discourage abuse by selecting every trait on the list.

Similarly, there could also be a “Wished” list that follows the same structure as the “Enjoyed” list. “Wished” would create opportunities for people to mention what else they would have liked from a book, and the collective traits of reviewers could further assist in someone’s decision to read a work.

Part Three: Building Trust, Respecting Time, And Creating Clarity

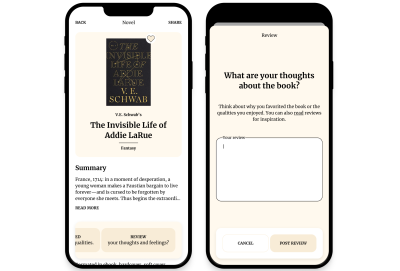

Every feature mentioned so far is enhanced by the final piece of our solution: written reviews. Allowing users to explain their thoughts, such as why they chose the qualities they enjoyed, gives potential readers a deeper understanding of the book they are considering.

However, remember the aforementioned stat that, on average, less than 5% of raters write reviews on Goodreads. That number becomes easier to understand when you consider that imparting meaningful feedback is a learned skill—you can find popular lessons on sites like Udemy, MasterClass, and others. Plus, add to that the fact that writing reviews can be more time-consuming than choosing ratings. Despite these hurdles, a site can offer guidance that motivates people to provide additional context about their thoughts.

In our solution, users are not merely given a blank text box and asked to write a review. The users are prompted to share their thoughts and receive suggestions to hone their feedback. The suggestions range dynamically, depending on a reader’s earlier choices. If they favorited a book, the prompt might ask why. If they chose the “Well-developed characters” option from the Enjoyed list, the prompt might ask how the characters are well developed. The prompt might also nudge users to read other people’s reviews for ideas.

The dynamic suggestions will particularly benefit books with sobering subject matter. For instance, only 1% of raters have written reviews for Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl on Goodreads. This is unsurprising when you consider the devastating historical context surrounding the book.

Commenting on typical story elements like pacing feels disingenuous to a book like Anne Frank’s — like giving a star rating to a friend telling you a story about themselves — but we should not shy away from talking about difficult literature, because discussing art can lessen our prejudices and expand our empathy. Prompts for these types of books might supply tips for close-reading a passage, mentioning what a story means to a reader, or asking how a book made a reader feel.

Finally, these features require regular usage to benefit readers. Growing an active community around them can be accomplished by building healthy communal habits, which hinge on voices having the capacity to be heard. Thankfully, one of the oldest features of the Internet can do a lot of the heavy lifting to solve this: commenting. Many sites offer the ability to comment on reviews, but several also employ a “Like” feature — the ability to press a button that “Likes” a review or comment — and liking comments can weaken the voices of a community.

Scammers can abuse the feature with bots to garner large amounts of likes and attention, people can waste time and emotional energy chasing likes, and the feature discourages people from using their words: all issues that fail our guiding principles, and even the ex-Twitter CEO admitted the like button compromises dialogue. Generating trust, meaningful usage of time, and clarity among users builds a safer environment for genuine conversation to spread, so comments should be protected from elements that detract from them.

Falling Action And Resolution: Let’s Be Thoughtful

Why any company utilizes a star rating system is a question for them. Reflecting on how easy to use and almost expected the scale has become, it’s likely companies simply copied a system that they believe is “good enough.” Maybe they were enthralled by the original Michelin Guide or Mariana Starke using exclamations points to denote special places of interest in guidebooks, but mimicry often flatters the originator more than the mimicker. Either way, the perks of ubiquity do not outweigh the vagueness that engenders numerous problems. At the forefront of those is stunting stronger connections between people trying to speak a shared language.

This article shows one solution for those problems, but there are others. Companies like The StoryGraph already provide alternatives to achieve thoughtful interactions around discussing literature, and people have additional ideas. Thoughtfulness can take a little longer to solve, but:

Let’s look beneath the surface of things and use our hearts — just as Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s eponymous Little Prince had to learn to do — to discover meaningful new territories in books and elsewhere. A good place to start would be reading or rereading that story, marveling at the stars dotting its illustrated skies, and writing a review to share what we each found buried within the pages.

Epilogue: What Readers Can Do Today

While the recommendations throughout this article are focused on how a company can change its rating and review system, companies can be slow to change. Fortunately, there are steps readers can take to be more thoughtful when reviewing the literature. A simple process today might look like this:

- Leave a star rating.

- Both users and algorithms pay attention to these ratings. If you ignore leaving a rating, you lessen the chance of readers discovering books they may love.

- Write a review. Consider some of these elements to streamline the process:

- Explain why you chose your rating.

- List common story qualities you enjoyed—these can vary depending on genre, but here is a starter list. Even better, write a sentence to say why you enjoyed specific qualities.

- Discuss a passage (or several) from the book that you found important.

- Mention what you wish you had known before reading a book and mark the review with “Spoilers” at the start if you include any.

- Link to other reviews that you think best sum up your perspective.

- Share your review.

- Not only will this help people find new literature, but it will also encourage them to write and share reviews.

You can use variations of this process to review other products, too. Remember that the most important part is that we use our words. This helps reduce confusion that might come from a lone star rating, and it helps us build stronger connections.

(ah, yk, il)