If you’ve been working with JavaScript for a while, you may be fairly familiar with DOM (Document Object Model) and CSSOM (CSS Object Model) scripting. Beyond the interfaces defined by the DOM and CSSOM specifications, a subset of methods and properties are specified in the CSSOM View Module, providing an API for determining and manipulating DOM element geometry to render interesting user interfaces on the web.

Prerequisites:

- A refresher on Coordinates System;

- An understanding of CSS Layout and Positioning;

- Writing callbacks in JavaScript;

- Some patience.

Table of Contents:

The CSSOM View Module

The CSS Object Model (CSSOM) is a set of APIs allowing CSS manipulation from JavaScript. Just like the DOM provides the interface for manipulating the HTML, the CSSOM allows authors to read and manipulate CSS.

The CSSOM View is a module of CSS that contains a bunch of properties and methods, all bundled up to provide authors with a separate interface for obtaining information about the visual view of elements. The properties in this module are predominantly read-only and are calculated each time they are accessed — live values.

Currently, the CSSOM View Module is only a working draft and under revision in the W3C’s Table of Specification. Its essence, therefore, is to define these interfaces, both already existing and new, in a manner that can be compatible across browsers.

Why Do Geometry Methods and Properties Matter At All?

From my perspective, there are a few reasons to try understanding and using the CSSOM View properties and methods.

First, it is not that the everyday user interface requires movable components to achieve its most basic user stories. Unless you’re building a game interface, you may not always need to make stuff movable on your website. Geometry properties are useful despite these because the ability to programmatically manipulate the visual view of DOM elements gives developers more superpowers for implementing dynamic user interfaces.

Kanban boards are implemented because components can be dragged and dropped at relevant sections. More content is loaded as users scroll to the bottom of a document because scroll position values are readable. So, while it may not seem immediately obvious, it is through knowing the accurate size and position information of elements that these features are achievable.

Second, when viewing HTML documents in a web browser, DOM Elements are rendered in visual shapes, so they have a corresponding visual representation made viewable/visual by browsers. Accessing the live visual properties of these DOM elements through the CSSOM View properties and methods gives an advantage over the regular CSS properties. And then you ask how:

- After setting the width and height properties of HTML elements in CSS, the CSS box-sizing property finally sets how an element’s total width and height are calculated. This creates an error-prone JavaScript if the value of our box-sizing changes.

- Second, there’s hardly any way to read an exact numeric value of an element’s width set to auto. And sometimes, we need the width in exact pixels and sizes.

Finally, it just seems way more flexible and useful to have a set of read-only lives values that can be relied on when writing some other code that manipulates the elements based on the current live values.

Element Node Geometry

Offsets

Coordinates specified using the “offset” model use the top-left corner of the element being examined or on which an event has occurred.

— MDN

Unlike other properties in the CSSOM View, offset properties are only available to HTMLElement nodes derived from the Element node. As such, you cannot read the offset properties of an SVGElement because they don’t exist.

Offset Left and Top

Using the read-only properties offsetLeft and offsetTop gives the x/y coordinates of an element relative to its offsetParent. The offsetLeft property returns the distance of the outer left border of the current element relative to the inner left border of the offsetParent while the offsetTop property returns the distance of the outer top border of the current element relative to the inner top border of the offsetParent.

Offset Parent

The offsetParent of any element is its nearest ancestor element which has a CSS position property that is not static, a <td>, <th>, or <table> element or at the base, the <body> element.

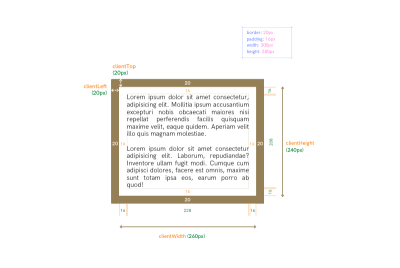

Offset Width and Height

These read-only properties provide the full outer size of element nodes. The offsetWidth is determined by calculating the total size of an element’s vertical borders, padding, and content, including any scrollbars that may exist. The offsetHeight is calculated in the same way using an element’s horizontal borders, padding, and content height.

Clients

Client Left and Top

In the most basic sense of it, these read-only properties give the size in pixels of an element’s left border width and the top-border width, respectively. In a deeper sense, however, the value of the clientLeft and clientTop properties of an element gives the relative coordinates of the inner side (outer padding) of that element from its outer side (outer border).

So, where a document has a right-to-left writing direction and left vertical scrollbars, the clientLeft will return coordinate values, including the size of the scrollbar. This is because the scrollbar displays between the inner side (outer padding) of that element from its outer side (outer border).

Client Width and Height

The read-only clientWidth and clientHeight properties of an element return the size of the area inside the element’s borders. The clientWidth property will return the size of an element’s content width and its vertical padding without the scroll bar. If there is no padding, then the clientWidth is just the size of that element’s content width. This is the same for the clientHeight property, which will return the size of an element’s content height plus horizontal padding, and in the absence of any padding, it will return just the content height as the clientHeight.

Scrolls

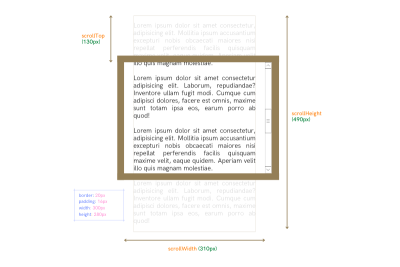

Scroll Left and Top

An element with no overflowing content on its x-axis or y-axis will return 0 when its scrollLeft and scrollTop properties are queried, respectively. An element’s scrollLeft property returns the distance in pixels that an element’s content is scrolled horizontally, while the scrollTop property gives the distance in pixels that an element’s content is scrolled vertically.

The pixels returned by the scrollLeft and scrollTop properties of an element are not always viewable in the scrollable viewport or client area due to the scrolling. The pixels can be viewed as representing the size of the area that has been scrolled away either to the left or to the top.

The scrollLeft and scrollTop properties are read-write properties, so their values can be manipulated.

Note: The scrollLeft and scrollTop properties may not always return whole numbers and can return floating point values.

Scroll Width and Height

The scrollWidth property of an element calculates its clientWidth plus the entire overflowing content on its left and right side, while the scrollHeight property calculates an element’s clientHeight plus the entire overflowing content on the element’s top and bottom side.

This is why if an element has no overflowing content on its x or y axes, its scrollWidth and scrollHeight properties will return the same values, respectively, as its clientWidth and clientHeight properties.

MDN explains the scrollWidth and scrollHeight property values as:

“… Equal to the minimum width or height the element would require in order to fit all the content in the viewport without using a horizontal or vertical scrollbar.”

Window and Document Geometry

The

Windowinterface represents a window containing a DOM document; thedocumentproperty points to the DOM document loaded in that window.

The geometry properties of the document loaded in the window and the window itself are relevant for several reasons. Sometimes we need to read the width of the entire viewport and the entire height of our document, other times, we even want to scroll a page to some definite extent and whatnot. Well, of course, the properties to read the relevant values and information are not left out in the CSSOM View Module.

Because there’s a root <html> element (labeled as Document.documentElement in the DOM) that defines the whole HTML document, we can also get the various height, width, and position properties of the HTML document by querying the root element.

Window Width and Height

The properties for calculating the width and height of the window are divided into inner and outer width and height properties. To calculate the outer width and height of the window, the outerWidth and outerHeight read-only properties are used, and they respectively return the width and height of the whole browser window.

To obtain the inner width and height of the window, the innerWidth and innerHeight properties are used. What is returned is the width and height (including scroll bars) of the entire viewport where the document is visible.

You may need to obtain the inner — viewport width or height of the window without the scrollbar and borders and, in such cases, use the clientWidth or clientHeight on the Document.documentElement, which is the root element representing the document.

Document Width and Height

We never set borders, padding, or margin values on the root element itself. Still, on elements contained in the Document, using the scrollWidth and scrollHeight properties on the root element Document.documentElement will return the document’s entire width and height.

Scroll Left and Top

As explored in the Element Node Geometry section, the scrollLeft and scrollTop properties return in pixels the size of the left or top scrolled away area of an element.

Thus, to determine the left or top scroll state of a document, using the scrollLeft and scrollTop properties on the Document.documentElement will return values representing the size of the part of the Document that has been scrolled away and is not visible in the window’s viewport.

The scroll state values of a document can alternatively and more preferably be obtained using the window.pageXOffset and window.pageYOffset values.

We can programmatically scroll the page in response to certain user interactions using scroll methods defined in the CSSOM View Module. Let’s consider them.

The scroll() and scrollTo() Methods

These two window methods are basically the same methods and allow you to scroll the page to specific (x, y) coordinates in the Document. The coordinates values represent an absolute position from the top and left corners of the document itself.

To simply visualize this, let’s run this code:

window.scrollTo(0, 500); //Scrolls the page vertically to 500 pixels from the page’s origin (0, 0). window.scrollTo(0, 500);

//Page stays at the same point.

After running window.scrollTo(0, 500) the first time, an attempt to run it a second time does nothing because the page is already at an absolute position of 500 pixels from the Document’s origin on its y-axis.

The scroll() and scrollTo() methods define x and y parameters for corresponding arguments representing the number of pixels along the horizontal and vertical axes, respectively, that you want the page scrolled to or a dictionary of options containing top, left, and behavior values.

The behavior value determines how the scroll occurs. It could be "smooth", which gives a smooth scrolling effect, or "auto", which makes the scrolling like a quick jump to the specified coordinates.

The scrollBy() Method

This is a relative scroll method. It scrolls the page relative to its current position and does not regard the Document origin whatsoever.

To examine this method, let’s use the code example from the scroll() and scrollTo() methods section:

window.scrollTo(0, 500); //Scrolls the page 500 pixels from the current position, say (0, 0), to (0, 500). window.scrollTo(0, 500);

//Scrolls the page another 500 pixels from the current position to (0, 1000).

Coordinates

Coordinate systems are the bane of how positions of elements are defined in the CSSOM View methods and properties.

When specifying the location of a pixel in a graphics context, its position is defined relative to a fixed point in the context. This fixed point is called the origin. The position is specified as the number of pixels offset from the origin along each dimension of the context.

The CSSOM uses standard coordinate systems, and these are generally only different in terms of where their origin is located.

Window and Document Coordinates

While the CSSOM uses four standard coordinate systems, the client and page coordinate systems are the most used in the CSSOM View Module. The dimensions or positions of elements are usually defined relative to either the document or the viewport.

Client Coordinates (Window Relative)

I found no better description of client coordinates than the one from MDN:

The “client” coordinate system uses as its origin the top-left corner of the viewport or browsing context in which the event occurred. This is the entire viewing area in which the document is presented. Scrolling is not a factor.

Client coordinates values are similar to using position: fixed in CSS and are calculated from the view port’s top left edge.

Page Coordinates (Document Relative)

The “page” coordinate system gives the position of a pixel relative to the top-left corner of the entire

Documentin which the pixel is located. That means that a given point in an element within the document will keep the same coordinates in the page model unless the element moves (either directly by changing its position or indirectly by adding or resizing other content).

Page coordinates values are similar to using position: absolute in CSS and are calculated from the Document’s top left edge. The page-relative position of an element will always stay the same regardless of scrolling, while its window-relative position will depend on the document scrolling.

Element Coordinates

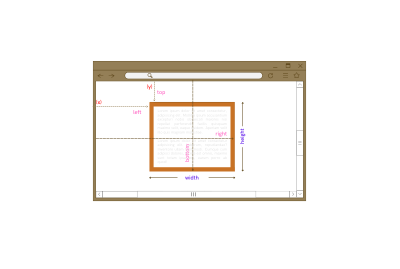

The Element.getBoundingClientRect() Method

This method returns an object called a DOMRect object whose properties are window-relative pixel positions and dimensions of an element. This is the one method you turn to when you need to manipulate an element relative to the viewport.

You should note that in certain cases, the returned DOMRect object does not always hold the same property values or dimensions for the same element. This is specifically true whenever transforms (skew, rotate, scale) are added to an element.

The reason for this is pretty logical:

In case of transforms, the

offsetWidthandoffsetHeightreturns the element’s layout width and height, whilegetBoundingClientRect()returns the rendering width and height. As an example, if the element haswidth: 100px;andtransform: scale(0.5);thegetBoundingClientRect()will return 50 as the width, whileoffsetWidthwill return 100.

— MDN

You can visualize this by clicking the display button in this pen below:

See the Pen [DOM Rect Properties [forked]](https://codepen.io/smashingmag/pen/KKedmYx) by Pearl Akpan.

The object returned by the getBoundingClientRect() method holds six dimension properties of the element the method was called on. These properties are:

xandyproperties return the x and y coordinates of the element’s origin relative to the window;topandbottomproperties return the y coordinates for the top and bottom edge of the element’s box;leftandrightproperties return x coordinates for the left and right edge of the element’s box;heightandwidthproperties return the entire width and height of the element as if the element is set tobox-sizing: border-box.

Mouse and Pointer Events Coordinates

All mouse or pointer event objects have coordinate properties that define both window-relative and document-relative coordinates where the mouse or pointer event occurs.

The window-relative coordinates for mouse events are stored in the clientX and clientY properties which denote the x and y coordinates, respectively.

On the other hand, the document-relative coordinates for mouse and pointer events are stored in the event object’s pageX and pageY properties for the x and y coordinates, respectively.

Use Cases

The APIs in the CSSOM View Module combine the most foundational yet useful methods and properties for accessing geometry properties of DOM Elements as rendered in the browser. Because these properties are live, they are more reliable in specific cases than their CSS values. But how can these APIs be used to create real-life user interface features?

We’d examine four everyday user interface solutions used in everyday modern websites and web apps that can be created using these APIs.

In this section, we will focus solely on the JavaScript code for implementing these user interface solutions, not the CSS nor HTML.

Scroll-to-top Component

The scroll-to-top button allows a user to quickly return to the top of the page with little effort. The CSSOM View API provides a simple method to achieve this with its scrollTo() and duplicate scroll() methods.

Here’s an implementation of the scroll-to-top button:

See the Pen [Scroll-To-Top [forked]](https://codepen.io/smashingmag/pen/VwdvWwK) by Pearl Akpan.

To achieve this, we need to create a scroll-to-top button. In our js file, we add a "click" event listener to this button:

scrollToTop.addEventListener("click", (e) => { window.scrollTo({left: 0, top: 0, behavior: "smooth"});

});

Then we register a handler for this event which executes (handles) what happens when this button is clicked. The code in the event handler calls the window’s scrollTo() method, with values that define the top of the page and the behaviour for the scroll.

For user experience, it’d definitely serve no use to see a scroll-to-top button if a user is already at the top of the page:

document.addEventListener("scroll", (e)=> { if(window.pageYOffset >= 500) { scrollToTop.style.display = "block"; } else { scrollToTop.style.display = "none"; }

});

The code above displays the scroll-to-top button only when the user has scrolled some distance by using the window.pageYOffset value to determine how far the page has been scrolled. If the page has been scrolled up to 500 pixels to the top, the scroll-to-top component becomes visible, and if not, it stays invisible.

Infinite Scrolling

With its implementation in popular social media, infinite scrolling allows users to scroll down a page; more content automatically and continuously loads at the bottom, eliminating the user’s need to click the next page.

Can you guess how the browser knows to load more content as a user scrolls down the page? How does one determine when a user has reached the bottom?

We know that document.scrollHeight gives the total height of a document, document.clientHeight gives the size of the viewable screen or viewport, and document.scrollTop or window.pageYOffset gives the size of the part of the document that has been scrolled away to the top. Could we take an intuitive guess that if document.scrollTop + document.clientHeight >= document.scrollHeight, then the user has reached the bottom of the page? I think so.

See the Pen [Infinite Scroll – [forked]](https://codepen.io/smashingmag/pen/OJEygVz) by Pearl Akpan.

This pen uses the infinite scrolling technique to load cards on a page until they reach their maximum count. At its most basic form, it imitates how e-commerce websites display search results for products. Let’s break down how this is achieved.

We use HTML and CSS to define the form and style of the cards container and the styles each element with the class of card should have. In our pen, we hard-code the first set of cards with HTML.

First, we get and assign to constants the following:

- card container element, which is the parent element for all the cards;

- status element that displays the current number of cards loaded.

We set a maximum on the number of cards that should be loaded on the page, and we also have a calculated value for the number of cards to be added to the page per load. So, we define a totalCardsNo and cardLoadAmount constants to store the values for the maximum number of cards and the number of cards to be added:

const cardContainer = document.querySelector("main"); const currentCardStats = document.querySelector(".currentCardNo"); const cardLoadAmount = 9; const totalCardsNo = 90; let lastIndex;

We need to write a test that checks when a user is at the bottom of the page and loads the cards. By our earlier guess, if document.scrollTop + document.clientHeight >= document.scrollHeight, then our user is at the bottom of the page.

In our pen, we add a scroll event listener to our document and use an arrow function to handle the scroll event. This function “handles” all card loading-related actions but does this only when the user is truly at the bottom of that page, that is, the condition document.scrollTop + document.clientHeight >= document.scrollHeight returns true:

document.addEventListener("scroll", (e) => { if (document.documentElement.scrollTop + document.documentElement.clientHeight >= document.documentElement.scrollHeight) { const children = cardContainer.children; lastIndex = children.length; } });

Once the user is at the bottom of the page, we initialize a constant, children, to hold an HTMLCollection of all the currently loaded cards, which are the current children of the cardContainer. The length of children also represents the index (not an array-like index) of the last card, and we store that value in the lastIndex variable.

In our code, we use the value of the lastIndex to know whether to load more cards or whether we’ve reached the totalCardsNo after which we can no longer load cards. If the value of lastIndex is less than totalCardNo, we load more cards:

if(lastIndex < totalCardsNo) { for(let i = 1; i <= cardLoadAmount; i++) { const tile = document.createElement("div"); tile.classList.add("card"); tile.textContent = `${lastIndex + i}`; cardContainer.appendChild(tile); } currentCardStats.textContent = `${children.length}`; } else { return; }

This second condition is contained in the first condition, and when it returns false, the event handler function adds no cards.

Animate on Scroll

One of the cooler features in websites and landing pages is components or elements that animate as the page is scrolled to a certain position (usually where the element should be visible) in a document.

Here’s a final result of a page with elements that animate on scroll. Let’s walk through how this is achieved:

See the Pen [Animate on Scroll [forked]](https://codepen.io/smashingmag/pen/oNyjwxz) by Pearl Akpan.

Because the idea of animating an element on scroll depends on when the element becomes visible, we need a test to figure out when an element has become visible, that is, has entered the viewport.

Our visible context is the viewport — the window; we need viewport-relative coordinates of an element. Remember,

The

Element.getBoundingClientRect()method returns aDOMRectobject providing information about the size of an element and its position relative to the viewport.

In a vertically scrolled page, an element is visible when its getBoundingClientRect().top value is less than the viewport’s height. In our pen, this is the condition we test to decide when to animate our element.

To start, we first get and store all the elements we will be animating in an array:

const animatingElements = Array.from(document.getElementsByClassName("item"));

Our test is summarised in this conditional below. There’s a slight addition to the simple condition that tests if the value of the element’s getBoundingClientRect().top is less than the height of the viewport (defined in document.documentElement.clientHeight).

We want the animation or transition on an element also to be visible, so adding 50 to an element’s getBoundingClientRect().top value sets a condition for the element to be animated when it is at least 50 pixels visible in the viewport:

if(el.getBoundingClientRect().top + 50 < document.documentElement.clientHeight) { el.classList.add("animated");

}

In our CSS, we create a class .animated, a utility class for an animation set to run once. Applying this class to an element runs the animation on it:

document.addEventListener("scroll", (e) => { animatingElements.forEach((el) => { if(el.getBoundingClientRect().top + 50 < document.documentElement.clientHeight) { el.classList.add("animated"); } else { return; } });

});

Now we add a scroll event listener to our document and register a handler that checks if the element is 50 pixels visible on the viewport. If the condition returns true, the animated class is added to the visible element once and for all.

Range Slider

While they may vary in implementation and use, range sliders are one of the more common web components. They are input controls that allow users to select a value or change a state from a control or sliding bar.

Take a look at the final result of this pen, where I implement a basic slider:

See the Pen [Range Slider [forked]](https://codepen.io/smashingmag/pen/QWxjgKJ) by Pearl Akpan.

We use HTML and CSS to define and style the elements designated with the classes .track and .thumb, respectively. A “drag” technique is the major implementation in sliders because the thumb is dragged within the track, which defines some sort of range.

So, we are getting and assigning the .track and .thumb elements to constants. Then we declare but don’t initialize the variables draggable and shiftX, to be used later:

const thumb = document.querySelector(".thumb");

const slider = document.querySelector(".track");

let draggable;

let x;

In its most basic sequence, drag-and-drop is achieved by:

- Moving the pointer to the object.

- Pressing and holding down the button on the mouse or other pointing device to “grab” the object (defined as a “

pointerdown” event). - “Dragging” the object to the desired location by moving the pointer to that location is defined as a “

pointermove” event). - “Drop” the object by releasing the button defined as a “

pointerup” event).

These sequences of actions are each defined in UI Events, specifically, the mouse and pointer events. Because as we saw in the Mouse and Pointer Events Coordinates section, these mouse events have document-relative and window-relative coordinate properties, and we would use them to create a drag-and-drop algorithm for our slider.

Events need handlers, so we declare handlers for the pointerdown, pointermove, and pointerup events each. The first handler we declare is a prepDrag function for the pointerdown event. The pointerdown event fires whenever the mouse or pointer is pressed down on the element that has a listener for the event:

function prepDrag(event) { draggable = event.target; x = event.clientX - draggable.getBoundingClientRect().left; document.addEventListener("pointermove", startDrag); document.addEventListener("pointerup", endDrag);

}The role of this handler is to prepare the element for moving. For instance, if the element was statically positioned, to prepare the element for a moving or “dragging” event, the prepDrag handler will have to set the element’s position to absolute or relative to be able to manipulate the element’s position through it’s top, left values.

Initialising the globally declared draggable and x in the prepDrag handler’s local scope makes the values accessible to the other handlers which will be executed in that scope.

Lastly, in this handler, we add the pointermove and pointerup event listeners to the document and not the thumb element. The reason is that the mousemove event triggers often, but not for every pixel. As such, it can cause unintended drag-and-drop responses. Adding the event listener to the document is a more reliable way to catch the mousemove event.

The second function, startDrag, handles the pointermove event, and it executes all the logic that determines how the thumb element moves and its positioning by manipulating its top and left style values:

function startDrag(event) { if (event.clientX < track.offsetLeft || event.clientX > slider.getBoundingClientRect().right){ return; } draggable.style.left = event.clientX - shiftX - track.getBoundingClientRect().left + 'px';

}

We want to constrain the dragging of the thumb to the boundaries of the track, such that even if the pointer is moved out of the track while pressed down, the thumb doesn’t get dragged out too.

This is implemented by manipulating the left style value of the draggable only when the mouse event’s clientX property is within the width of the track. Thus, while the pointer is pressed down and moving, the draggable element’s left position style only changes if the mouse event’s clientX value is not less than the track’s offsetLeft value nor greater than the track’s getBoundingClientRect().right value.

The last function, endDrag, handles the pointerup event. It removes the pointermove and pointerup event listeners from the document:

function endDrag() { document.removeEventListener("pointermove", startDrag); document.removeEventListener("pointerup", endDrag);

}

Since these events are set to initiate in a continuous sequence, it makes sense that their handlers don’t continue to run once the pointerdown event (which begins the sequence) ends:

thumb.addEventListener("pointerdown", prepDrag);

Finally, we add a pointerdown event listener to the thumb element to register a handler for the very first event we listen for.

Conclusion

The use cases covered in this article merely scratch the surface of what is achievable with CSSOM View Module API.

When the heavy DOM manipulation is not considered, I believe the methods and properties in this API give us a lot of tools to customize the geometric properties of web components to suit various interface needs.

(yk, il)