Like many things, a design system isn’t ever a finished thing — it’s a journey. How we go about that journey can affect the things we produce along the way. Before diving in and starting to plan anything out, be clear about where the benefits and the risks might lie.

It can be easy to assume that everyone needs a design system, that you can pick one off the shelf or put one together pretty quickly, and your problems are over. As with many things on the web, your mileage may vary. What I want to share with you are some observations from the last few years, not just from myself but from people that have been part of our design systems journey at Auto Trader.

We started in a very different place to where we find ourselves today: loads of inconsistencies, duplication, communication that needed to be improved, and ultimately the quality and speed of output weren’t what they should be. Our practices today have dramatically improved on so many fronts, one aspect being our design system.

The Problem Space

There are so many really great articles out there about design systems; how to design and or code them, but let’s step back to the beginning.

- What problems do you feel that a design system might address?

- Why do you think a design system might ameliorate them?

If you’re clear on your specific issues, it helps not only inform your solution but help with a narrative that might resonate with stakeholders.

Even at this early stage, language matters. What do you think a design system is? As part of your proposed solution, is it actually a style guide, a component library, a design library, or a more well-rounded system? You might not need something all singing and dancing for your project or organization. Starting with one aspect doesn’t mean you can’t evolve into something else later!

So, you have a sense at this stage that you may be on a greenfield project — or as we were, adding in the foundations to a large traffic site that already existed — and you may have a view on what form your design system might take. Before diving in and starting to plan anything out, we can be clearer with ourselves about where the benefits and the risks might be.

You could start as simply as making lists:

| Potential Benefits |

|---|

| + Encourages greater communication between disciplines. |

| + Greater quality and consistency of our output. |

| + Should be able to get new content or features to market quicker. |

| Potential Risks |

|---|

| – Other colleagues might not want to use it. |

| – It takes too much time to get it to a place where it produces value. |

| – We use the wrong tooling or software. |

You could take this further if in your organization you need a business case and use a SWOT Analysis as a way to form something robust. This allows you to look at the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and risks, and it is often used in business planning. It doesn’t have to be a labored task, but it can help to look at your potential system from other viewpoints.

Mitigating avoidable risks is important. Being clear with yourself about what could go wrong, and what you can do about it helps to make your solution more robust. On the flip side, the potential benefits can lead us into thinking about what our definition of success might look like — our “north star”. What good might look like for your system?

From the vision piece, you need to be able to start somewhere, which leads us to more avenues of questioning:

What kind of a system helps you to progress in a sustainable way for the needs and resources you have?

Could a style guide be all you need?

Is some form of a component library enough to get you working in a better way?

What current and potential audiences might the system have?

You may start with it being a design project to address consistency across a design team, but acknowledging that for it to evolve it needs a wider range of skills which is a kind of debt that will be built-in. In some cases, much as we did, an initial solution may make sense to be replaced by something else further down the line. Not being wedded to a particular solution can be hard, especially if it’s “your baby”, but going back to that north star, and the purpose of the system gives us a healthy reminder of when it can be time to let go.

What To Measure?

Many things may be measurable from the sentiment of attitudes towards the system and experience using it through to the number of components in the system and actually used on the site (or in your app). Actually, looking at where a given component is used can have some useful benefits when it comes to later stages of working with your system, as it helps to gauge the risk of a proposed change, and where you might see some impact.

From your picture of what success looks like, are there measurables that can help tell your story to stakeholders or that give you a sense of how well you’re doing? While in our scenario, we didn’t set out a list of KPIs; we were clear that it should power the majority of the consumer website and look into how or when our native apps may work with it. On the back of our refresh project, we’d be taking care of most of the site outside of focus consumer journeys where our team would act more as support for the teams around them. That gave us confidence that if we were able to deliver output to the site on a regular basis, we would be able to meet that vision we’d set out.

Assuming that you have a well-rounded design system, you may have designers, content designers, test engineers, front-end and back-end developers, product people, delivery folks — all potentially finding this as a part of their lives. Again, the language that we use matters to ensure there’s a shared understanding across domains.

What’s In A Name?

One key thing that helped us was naming things clearly across disciplines, so we’re referring to the same thing and being clear on its intent. That purpose transcends specialisms and helps give clarity to what an object in your design system is for, what problem it solves, or what role it plays. That clarity of purpose pays off in many ways over time.

Using a well-worn example, a button is a button, isn’t it? Well, not always.

While the visual asset may have the appearance of a button, when it comes to applying it to code, is this a button tag?

Is it a link that looks like a button (which is a debate in itself!)?

In your framework, is it an internal router link?

There is room for debate, but we ended up in a place where the visual asset gave us the language to talk about it, and the technical execution may differ based on a use case. We’re all now talking about buttons, even when the actual code differs.

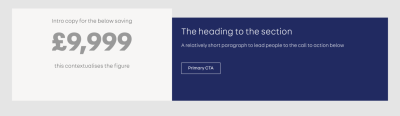

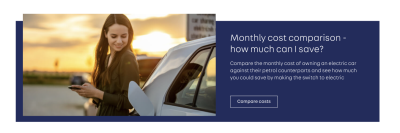

We have a component, originally called the “Promo Section”; it was intended for calling out key parts of a value proposition. The following example shows where intent and language differ — as it’s now become a more generic content block. The work now is to look at use cases in the wild and choose as a team: whether we accept that’s what it is and capture it or look at whether it needs to be more than one component based on those use cases.

There’s a lot to think about, and we’ve not even touched upon the design files or what your code might look like yet!

People-Powered

You might start as a team of one or have a group around you to make this happen, but defining roles and responsibilities early on is important. Having an amazing Figma library is great, but if it doesn’t at some point become code and have a release process, it’s a collection of pictures of what could be. Underneath a lot of what a design system appears to be is a mechanism for fostering better communication and understanding. A new system might start from any discipline, but it needs others to be truly impactful.

Not everyone is fortunate enough to have dedicated time or resources to make a design system, so it’s often a balance between how much time it might need to produce some value. You might not be able to start with the ideal system you have in mind but can find a way of communicating the value proposition you believe the design system has. Going back to the problem space, what might be a great example to start with? Looking at your “north star”, what demonstrates the potential through a hack or experiment?

Ownership And Community

I’ve felt less of an owner of the system and increasingly more of a shepherd. The system isn’t mine — it’s shared. The responsibility of ensuring it persists ideally shouldn’t rest on any individual, as if things go well, this design system will be a major asset to your organization.

Designing the “people bit” and structures around the system itself pays off. Initially, we kept those directly involved to a minimum, through availability and, in part, through choice. There were some fundamental decisions to make, and test out, and try to break.

With some great support from our engineering colleagues, we both worked on output (making the first landing pages) as well as road-testing (and breaking) the design system mechanism itself. Alongside, we’d start talking more broadly around the business about what the design system was, how it was different from previous projects, and to set and manage some expectations.

As we weren’t just making the design system but working through refreshing the site, we worked in the open, with our plan and breakdown on a board, so whenever people came by our area of the office, we could talk them through it and get some initial feedback. At that early stage, we also talked through the refresh of the site (and so the design system) with departments that might not normally be in the loop.

Outreach

Taking time to explain to different audiences, in their domain language, what it is and why it matters can help you to gain advocates, and the advocacy model can help foster a community around the system, as it grows and matures.

In the earlier days, having “good news stories” or case studies around what the design system has helped us to achieve and amplify the messaging you’re trying to spread. In our case, we were able to be far more reactive with content, because of the fact our design system had solved problems that mapped to that kind of project. We could then have quick conversations focused on what the content was trying to achieve, and we were able to get something live far quicker than we previously had done, and to the same quality as other parts of the site.

Creating a community around the design system can’t be forced. They don’t just happen and can take time to nurture. Some of helping it along is that sense of shared ownership, which can mean many things, including being able to actively contribute or participate. How can people outside the immediate team around the system propose new additions or changes? Is there a clear feedback mechanism? One of the best examples I remember seeing was in GDS (Gov.uk Design System).

There’s some inherent tension, as there’s a balance between community and engagement, contribution and a governance process that has rules and processes. How this coalesces around something that works for you and your circumstances will differ. Governance: how you define responsibilities and workflows can become as much established through the community as imposed upon it. Having something as a starting point that can be critiqued is often easier than a blank canvas!

Note: Although it’s a few years old, it’s worth checking out Brad’s article from 2019.

While there’s a huge amount of care and effort involved in creating and maintaining, everything in the design system needs to be up for debate and a challenge from the community you aim to form around it. All of this helps with engagement, but also helps to make what’s in the system more robust; whether that’s through design changes, code improvements, or just providing better documentation.

Workflow, Communication And Evolution

This flex between what a specialism needs within its domain and what allows for broad communication is really important. How your work goes from inception to somehow appearing on a live website is big stuff. This workflow doesn’t yet dictate the tooling or presentation of your system but underpins its value.

You might start mapping out a workflow like this:

- A need emerges;

- The team (TBC) discusses it, and the outcome of this forms a proposal;

- This proposal is worked on and taken to a crit session;

- Once complete, the component is reviewed and made available to the system;

- Once tested, it can be used;

- When used in-situ, gather feedback and see how it performs “in the wild”.

Considering how to manage change isn’t always easy. We chose to start our components in an opinionated way; they’d do one job and wouldn’t include much logic. While you could craft them in a more futureproof way, you can’t predict what change is needed, but enabling and facilitating change is an important part of any design system. A new bit of content needs to be passed in a different style of a call to action.

How should we not just update the component itself but its uses all over the site?

Baking in some assumptions, that changes are just possible but actually desirable, is really important.

How do you roll out a breaking change across your codebase?

If you update your component in your design tool of choice, what knock-on effects are there?

Each item in a proposed workflow might have the depth to be explored. For us, we wanted to make it feel like a “push” when we updated a component, so the live site would always be up to date — every change would be versioned and released immediately to the site like we “pushed” it out. Under the hood, we use conventional commits to automatically trigger versioning of our code, which runs our build processes that include automated tests.

Once pulled into an app in one of our React apps, future builds of the design system would trigger upstream builds for that app, so every intentional change is pushed out to the site, and in theory, the components should always be up to date, unless a developer specifically needs otherwise. Explaining that process hopes to illustrate the simple workflow intent, to “feel like a push” actually involved a chunk of engineering to ensure pipelines and build process worked as we’d expect. We also have the ability to flag a potentially breaking change, as a beta release to manually pull into apps to validate before making that change permanent.

Understanding Change And Evolution

Some components might start off looking or functioning in similar ways, but how might this play out over time? It might make sense to build them from a shared look and feel or set of functionality. A better way to solve a given problem emerges, and so this link to another component no longer makes sense.

There’s an element of understanding that we bake in potential tech or design debt into the components we create. While there’s a contract in the code between your component and its context of use that needs to be preserved, the way it’s constructed can change. So, the balance lies between not over-engineering every component when it’s created and considering how change might happen with a sense of how scenarios might play out.

Back to our example of the Promo Section I mentioned earlier. This has been used for more than its initial intent, but we can learn from that. There are some options we can explore:

Do we keep it as it is and expand on its intended purpose?

Do we look at what use cases have emerged and split this into multiple components?

Is it something that needs reevaluating entirely?

That second option is worth exploring. Maybe this split into two components means that they still look the same? If they do, maybe they use some of the same mark-up and styles and share that common base. Following this through, we might have better or different ways of solving problems these components cause today. Using the same base is a practical short-term solution, and realistically, we can’t know if we’ll ever change them in the future. If one diverges its presentation, have we baked in some debt, or do we accept that and factor that into future changes?

The Source of Truth and Making Proposals

One early principle we had was that live code trumps the design. That’s a controversial statement in some circles, so I’ll explain: our users are actively using and experiencing our design system components. As good as the work and thinking are in your design tool, it’s unrealized potential until it makes its way through to the live website. Keeping naming, structure, and change tight prevents design work from diverging too far too soon for the system. That doesn’t mean that play and experimentation are in any way limited, just that they should exist outside of the system until the concept is ready to promote. And so, there’s another aspect of change, when change is needed or new components are required.

We’ve done some work around our proposal structure (which as I write is in its early days), but so far so good. A proposal starts by recognizing the component’s purpose, i.e. what problem it was created to solve. That actually starts the basics of the documentation for it too, and capturing that early. We have regular open-invite design system-focused sessions, where proposals can be discussed and challenged, and from that designs can be critiqued, and code could be submitted as pull requests. As a collective, we try not to make the process too labored but also hold a proposal to some level of rigor.

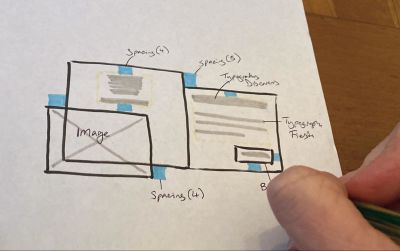

A proposal might include some of these:

- Purpose/Intent

What problem does the suggested component solve? - Use Cases

Often a component would be proposed to the design system if it was needed in more than one place. What use(s) does it have, and how does the use case map to its intended purpose? - Anatomy

What are the elements, spacing units, and typography that make the component? (Early experiments with this seem useful for us.) - Related Components

If this isn’t a fit for what you want, what others do similar jobs?

What we’ve found is that this actually becomes part of the documentation, before a component is actually added to the system!

In the early days or thinking about our approach, we also had the notion of ‘lenses’ to look at components/design patterns. Different ways to turn the work around in your mind and see them from different angles.

Some might be reminders, some technical, some not:

| Testing | What kinds of testing gives us confidence in this component? Visual regression (VRT), automated tests, manual testing? |

| Tracking | Is this something that should be tracked in some way? What should we be tracking? Is tracking dependent on a state or interaction? |

| Accessibility | How much can we bake in to ensure that everything is as inclusive as we can make it? Is the mark-up semantic? Does it need to provide options to ensure it is based on context of use? |

| Content | What do our content designers need from this component? Is there guidance we can add with how to get the best use of it? |

| SEO | Is there anything this component should do to consider how it can support search engines beyond the content and accessibility lenses? Is there a relevant schema that may be worth including? |

| Performance | Is there anything we need to consider about how this performs? Does it use a 3rd party or assets that aren’t already present? How can we moderate its impact? What is the component’s responsibility or that of the app it’s consumed in? |

| Motion | Should it have any animations or transitions in the component or a state of it? Ensure it works without (prefer-reduced-motion) |

| States | Loading/unloading

Interaction states (focus, hover, disabled, etc) View states (is it in or out of the visible viewport? See intersection observer) |

| Triggers & actions | Should some functionality be triggered? Often this would be linked to an interaction state but could be more open than that |

| Viewport events | Has the resize or orientation change event been triggered on the viewport? |

| Coding defensively | What if we don’t have the data or content we expect to be passed to it? What if we have too much? Can the component fail in a graceful way? |

By no means, this is an exhaustive list, but it might help with how you can think about your components differently. Think of some useful prompts of your own, based on how your site works — forming that together might be a great way to bring some different disciplines together!

Conclusion

There’s a lot to consider, but it doesn’t have to all be done at the beginning. Governance, workflow, communication, and community are all really important and, more often than not, need to be considered as a part of the design system itself. These are the things that enable contributions and manage change. It allows for a challenge to establish patterns as much as it helps roll out work using a raft of solved problems. Acknowledging when decisions will lead to tech/design debt and being clear on what level of debt is acceptable might not be something that’s clear from the beginning but discussing it helps with making informed decisions.

Some form of design system might be a part of your work from a lone freelancer to a massive multi-department organization, so your mileage may vary, but hopefully, you’ll look a little broader when starting a design system. The aspects around the community and the kinds of debt you can accrue might resonate across all kinds of systems.

Like many things, a design system isn’t ever a finished thing — it’s a journey. How we go about that journey can affect the things we produce along the way. While we’ve learned a lot, there’s still a lot further to go. There will always be new challenges, and change is good.

As Ryan DeBeasi said in his article:

“A design system isn’t just code, or designs, or documentation. It’s all of these things, plus relationships between the people who make the system and the people who use it.”

— Ryan DeBeasi, Design Systems Are About Relationships

I look forward to hearing how you get on, and how you make these aspects around the artifacts of your design systems work for you!

(vf, yk, il)