Friction in cooperation between designers and developers is fueling an ever-evolving discussion as old as the industry itself. We came a long way to where we are today. Our tools have changed. Our processes and methodologies have changed. But the underlying problems often remained the same.

One of the recurring problems I often tend to see, regardless of the type and size of the team, is maintaining a reliable source of truth. Even hiring the best people and using proven industry-standard solutions often leaves us to a distaste that something definitely could have been done better. The infamous “final version” is often spread across technical documentation, design files, spreadsheets, and other places. Keeping them all in sync is usually a tedious and daunting task.

Note: This article has been written in collaboration with the UXPin team. Examples presented in this article have been created in the UXPin app. Some of the features are only available on paid plans. The full overview of UXPin’s pricing can be found here.

The Problem With Design Tools

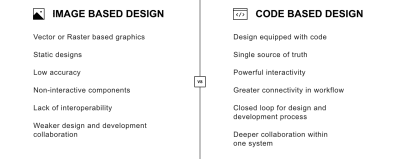

Talking of maintaining a source of truth, the inefficiency of design tools is often being indicated as one of the most wearing pain points. Modern design tools are evolving and they are evolving fast with tremendous efforts. But when it comes to building the bridge between design and development, it’s not rare to get the impression that many of those efforts are based on flawed assumptions.

Most of the modern design tools are based on different models than the technologies used to implement the designs later on. They are built as graphic editors and behave as such. The way layouts are built and processed in design tools is ultimately different from whatever CSS, JavaScript and other programming languages have to offer. Building user interfaces using vector (or even raster) graphics is constant guesswork of how and if what you make should be turned into code later.

Designers often end up lamenting about their creations not being implemented as intended. Even the bravest efforts towards pixel-perfect designs don’t solve all the problems. In design tools, it is close to impossible to imagine and cover all the possible cases. Supporting different states, changing copy, various viewport sizes, screen resolutions and so on, simply provide too many changing variables to cover them all.

On top of that come along some technical constraints and limitations. Being a designer without prior development experience, it is immensely hard to take all the technical factors into account. Remember all the possible states of inputs. Understand the limitations of browser support. Predict the performance implications of your work. Design for accessibility, at least in a sense much broader than color contrast and font sizes. Being aware of these challenges, we accept some amount of guesswork as a necessary evil.

But developers often have to depend on guesswork, too. User interfaces mocked up with graphics editors rarely answer all of their questions. Is it the same component as the one we already have, or not? Should I treat it as a different state or as a separate entity? How should this design behave when X, Y, or Z? Can we make it a bit differently as it would be faster and cheaper? Ironically, asking whoever created the designs in the first place is not always helpful. Not rarely, they don’t know either.

And usually, this is not where the scope of growing frustration ends. Because then, there’s also everyone else. Managers, stakeholders, team leaders, salespeople. With their attention and mental capacity stretched thin among all the tools and places where various parts of the product live, they struggle more than anyone else to get a good grasp of it.

Navigating prototypes, understanding why certain features and states are missing from the designs, and distinguishing between what is missing, what is a work in progress, and what has been consciously excluded from the scope feels almost impossible. Quickly iterating on what was already done, visualizing your feedback, and presenting your own ideas feels hardly possible, too. Ironically, more and more sophisticated tools and processes are aimed at designers and developers to work better together; they set the bar even higher, and active participation in the processes for other people even harder.

The Solutions

Countless heads of our industry have worked on tackling those problems resulting in new paradigms, tools, and concepts. And indeed a lot has changed for the better. Let’s take a quick look and what are some of the most common approaches towards the outlined challenges.

Coding Designers

“Should designers code?” is a cliché question discussed a countless number of times through articles, conference talks, and all other media with new voices in the discussion popping up with stable regularity now and then. There is a common assumption that if designers “knew how to code” (let’s not even start to dwell on how to define “knowing how to code” in the first place), it would be easier for them to craft designs that take the technological constraints into account and are easier to implement.

Some would go even further and say they should be taking an active role in the implementation. At that stage, it’s easy to jump to conclusions that it wouldn’t be without sense to skip using the design tools altogether and just “design in code”.

Tempting as the idea may sound, it rarely proves itself in reality. All the best coding designers I know are still using design tools. And that’s definitely not due to a lack of technical skills. To explain the why is important to highlight a difference between ideation, sketching, and building the actual thing.

As long as there are many valid use cases for “designing in code”, such as utilizing predefined styles and components to quickly build a fully functional interface without bothering yourselves with design tools at all, the promise of unconstrained visual freedom is offered by design tools still stands of undeniable value. Many people find sketching new ideas in a format offered by design tools easier and more suited for the nature of a creative process. And that is not going to change anytime soon. Design tools are here to stay and to stay for good.

Design Systems

The great mission of design systems, one of the greatest buzzwords of the digital design world in the last years, has always been exactly that: to limit guesswork and repetition, improve efficiency and maintainability, and unify sources of truth. Corporate systems such as Fluent or Material Design have done a lot of legwork in advocacy for the idea and bringing momentum to the adoption of the concept across both big and small players. And indeed, design systems helped to change a lot for the better. A more structured approach to developing a defined collection of design principles, patterns, and components helped countless companies to build better, more maintainable products.

Some challenges had not been solved straight away though. Designing design systems in popular design tools hampered the efforts of many in achieving a single source of truth. Instead, a plethora of systems has been created that, even though unified, still exist in two separate, incompatible sources: a design source and a development source. Maintaining mutual parity between the two usually proves to be a painful chore, repeating all the most hated pain points that design systems were trying to solve in the first place.

Design And Code Integrations

To solve the maintainability headaches of design systems another wave of solutions has soon arrived. Concepts such as design tokens have started to gain traction. Some were meant for syncing the state of code with designs, such as open APIs that allow fetching certain values straight from the design files. Others were meant for syncing the designs with code, e.g. by generating components in design tools from code.

Few of these ideas ever gained widespread adoption. This is most probably due to the questionable advantage of possible benefits over the necessary entry costs of still highly imperfect solutions. Translating designs automatically into code still poses immense challenges for most professional use cases. Solutions allowing you to merge existing code with designs have also been severely limited.

For example, none of the solutions allowing you to import coded components into design tools, even if visually true to the source, would fully replicate the behavior of such components. None until now.

Merging Design And Code With UXPin

UXPin, being a mature and fully-featured design app, is not a new player on the design tools stage. But its recent advancements, such as Merge technology, are what can change the odds of how we think about design and development tools.

UXPin with Merge technology allows us to bring real, live components into design by preserving both their visuals and functionality — all without writing a single line of code. The components, even though embedded in design files, shall behave exactly as their real counterparts &mdah; because they are their real counterparts. This allows us not only to achieve seamless parity between code and design but also to keep the two in uninterrupted sync.

UXPin supports design libraries of React components stored in git repositories as well as a robust integration with Storybook that allows usage of components from almost any popular front-end framework. If you’d like to give it a shot yourself, you can request access to it on the UXPin website:

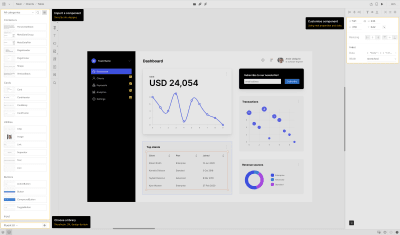

Merging live components with designs in UXPin takes surprisingly few steps. After finding the right component, you can place it on the design canvas with a click. It will behave like any other object within your designs. What will make it special is that, even though being an integral part of the designs, you can now use and customize it the same as you would in code.

UXPin gives you access to the component’s properties, lets you change its values and variables, and fill it with your own data. Once starting the prototype, the component shall behave exactly as expected, maintaining all the behaviors and interactions.

In your designs, you can mix and match an unlimited number of libraries and design systems. Apart from adding a library of your own, you can also choose among a wide variety of open-source libraries available out of the box such as Material Design, Fluent UI, or Carbon.

Using a component “as is” also means that it should behave according to the change of the context, such as the width of the viewport. In other words, such components are fully responsive and adaptable.

Note: If you would like to learn more about building truly responsive designs with UXPin, I strongly encourage you to check out this article.

Context may also mean theming. Whoever tried to build (and maintain!) a themeable design system in a design tool, or at least create a system that allows you to easily switch between a light and a dark theme, knows how tricky of a task it is and how imperfect the results usually are. None of the design tools is well optimized for theming out of the box and available plugins aimed at solving that issue are far from solving it fully.

As UXPin with Merge technology uses real, live components, you can also theme them as real, live components. Not only can you create as many themes as you need, but switching them can be as quick as choosing the right theme from a dropdown. (You can read more about theme switching with UXPin here.)

Advantages

UXPin with Merge technology allows a level of parity between design and code rarely seen before. Being true to the source in a design process brings impeccable advantages for all sides of the process. Designers can design with confidence knowing that what they make will not get misinterpreted or wrongly developed. Developers do not have to translate the designs into code and muddle through inexplicit edge cases and uncovered scenarios. On top of that, everyone can participate in the work and quickly prototype their ideas using live components without any knowledge about the underlying code at all. Achieving more democratic, participatory processes is much more within reach.

Merging your design with code might not only improve how designers cooperate with the other constituents of the team, but also refine their internal processes and practices. UXPin with Merge technology can be a game-changer for those focused on optimization of design efforts at scale, sometimes referred to as DesignOps.

Using the right source of truth makes it inexplicably easier to maintain consistency between the works produced by different people among the team, helps to keep them aligned, and solves the right problems together with a joint set of tools. No more “detached symbols” with a handful of unsolicited variations.

At the bottom line, what we get are enormous time savings. Designers save their time by using the components with confidence and their functionalities coming out of the box. They don’t have to update the design files as the components change, nor document their work and “wave hands” to explain their visions to the rest of the team. Developers save time by getting the components from designers in an instantly digestible manner that doesn’t require guesswork and extra tinkering.

People responsible for testing and QA save time on hunting inconsistencies between designs and code and figuring out if implantation happened as intended. Stakeholders and other team members save time through more efficient management and easier navigation of such teams. Less friction and seamless processes limit frustration among team members.

Disadvantages

Taking advantage of these benefits comes at some entry costs though. To efficiently use tools such as UXPin in your process, you need to have an existing design system or components library in place. Alternatively, you can base your work on one of the open-source systems which would always provide some level of limitation.

However, if you are committed to building a design system in the first place, utilizing UXPin with Merge technology in your process would come at little to no additional cost. With a well-built design system, adopting UXPin should not be a struggle, whilst the benefits of such a shift might prove drastically.

Summary

Widespread adoption of design systems addressed the issues of the media developers and designers work with. Currently, we can observe a shift towards more unified processes that not only transform the medium but also the way we create it. Using the right tools is crucial to that change. UXPin with Merge technology is a design tool that allows combining design with live code components and drastically narrows the gap between the domains design and development operate in.