Matt Mullenweg (creator of WordPress) has expressed interest in having the WordPress editor comply with the Block Protocol, a recently-released specification which aims to have “blocks” be portable across applications.

When I learned about Matt’s interest, I got quite thrilled, since such a development could produce several positive consequences for WordPress and other actors too. My excitement comes from what happened with GraphQL, where the release of servers, clients, and tools adhering to a common specification has produced a rich ecosystem; and from my own development of a plugin that could support new features through the protocol.

In this article, I’ll analyze these, and several other potential outcomes. But before doing so, let’s explore the context to the story: what is a block, what the Block Protocol aims to achieve, and how it all connects to WordPress.

What Is A Block?

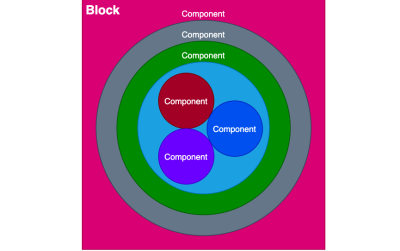

When working with JavaScript-based libraries, such as React or Vue, we work with “components” which are pieces of code (usually composed of HTML, CSS styles, and JavaScript) grouped together. A component renders a defined layout or produces a specific functionality, such as an image carousel, an event calendar, or a simple header. To render content, the component may fetch data from the server via an API call, or have the data provided via props by some ancestor component that wraps it. By having its data injected, the component becomes reusable, able to produce different outcomes for different contexts or applications.

A “block” is also a component, but it is high-level, asserting a definitive purpose, and defining the requirements to produce the desired layout or functionality. It is the outermost component from the hierarchy of components wrapping each other, so it has a bird eye’s view of them.

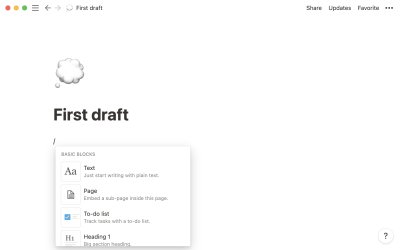

We can play with components when using Notion, where every action (whether it is writing text, adding a bullet list, creating tables or anything else) is accomplished by inserting one or another block:

A block is a concept, not a technology. It can be implemented on any language: not only JavaScript to power clients, but also a server-side language to render a layout. Blocks must not be confused with web components, which is a collection of technologies to produce components. They are not mutually exclusive either — we can use web components to create a block.

Taking an analogy from the agile world: if an MVP, or Minimum Viable Product, is the least piece of work to launch and market a commercial project, we could think of the block as a MUC, or Minimum Usable Component, as a basic unit of work that gives coherence and personality to an application.

What Is The Block Protocol?

Components are fairly reusable. For instance, searching for “react component” on npm will produce plenty of libraries offering components that we can immediately import into our React applications.

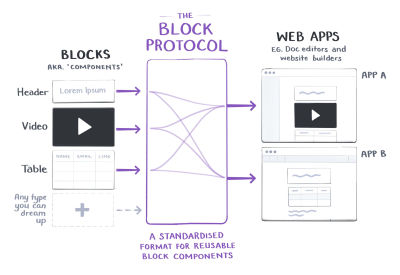

Blocks, however, are a different story, because they are mostly designed for some specific application. While the block must provide the means to interact with it (such as offering an API to initialize it and render it, or exposing a JSON schema describing what data it needs as input), these means are usually dependent on the application where the block lives, so we can’t reuse a block across applications.

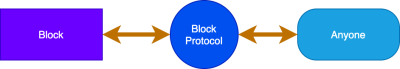

That’s where the Block Protocol comes in. It provides a specification for blocks and applications to satisfy, aiming to allow blocks to be embedded within any application, not only the one they were designed for. Same as with components, blocks could then become reusable across applications.

Reusable Blocks And WordPress

Since version 5.0 from December 2018, the default experience in WordPress for creating content has been via blocks. Since its recently-released version 5.9, this experience has been expanded into creating website layouts through Full Site Editing (FSE). The modern experience for creating both content and a theme for WordPress is now via blocks.

When Joel Spolsky recently introduced the Block Protocol to the world, he did it from his WordPress-powered blog. As he explained how he used blocks to compose his post, he suggested that blocks should be reusable across the web. This was a direct suggestion that WordPress blocks should be reusable across the web, which Matt Mullenweg immediately agreed to.

Let’s analyze next what consequences we can foresee from such a development if it were to happen.

Who Will Use The Block Protocol?

This is Joel’s description of how the Block Protocol came to be:

“[The implementation of a block by different applications] is completely proprietary and non-standard.

I thought, wouldn’t it be cool if blocks were interchangeable and reusable across the web?

[…] Users might want to use a fancier block that they saw in WordPress or Medium or Notion, but my editor doesn’t have it. Blocks can’t be shared or moved around very easily, and our users are limited to the features and capabilities that we had time to re-implement.”

While I agree 100% with Joel’s motivation, I believe that expecting Notion or Medium to implement their blocks using a publicly-shared protocol is unrealistic. Why would they? Of course, they want their blocks to be proprietary. If Medium made its own blocks available to any application to embed, then anyone could overnight offer a Medium-clone and divert traffic away from them. Same for Notion. Being commercial platforms aiming to gain users based on their advanced features and great user experience, there is nothing in it for them to give away their technology (that is, they could still comply with the protocol for their own internal use, but then we, outsiders, will not benefit from it).

So, who else, in addition to WordPress, may want to comply with the Block Protocol? Who will benefit from it?

My impression is the following:

- Teams without a big budget

Instead of developing their own blocks from scratch (which is effort-intensive and as such demands a dedicated team), a website could be built using blocks developed by someone else; the team could then just customize the blocks for their own application and possibly contribute back to the blocks’ open-source code. - Applications that need to catch up to offer a compelling user experience

Medium and Notion are popular because their user experience is appealing. If we could provide a similar user experience for our websites (and for very little or no cost), why shouldn’t we?

This is not necessarily limited to small websites, but can also be the case for popular websites that are falling behind in the block race. For instance, some time ago I noticed Mailchimp experimenting with a modern block-based editor for composing newsletters (I can’t find this new editor anymore… have they taken it away?). I had tried it out, but it was buggy, so I reverted to the classic split-pane editor (which also supports blocks but of a different kind, not editable in place). Might Mailchimp benefit from using blocks offered by WordPress?

- Content Management Systems

Similar to WordPress, other CMSs can also benefit from offering ready-to-use blocks to build applications. Indeed, Drupal Gutenberg has attempted to bring the WordPress editor over to Drupal. Thanks to the Block Protocol, this task could be easier to accomplish. - Open-source projects

Similar to components available via npm, if blocks were reusable, then it’s only a matter of time before the community starts building blocks and offering them freely as open-source (whether via GitHub, the Block Hub, or somewhere else) for the benefit of everyone.

How Will Others Benefit From WordPress Joining The Block Protocol?

We just explored who may benefit from, and as such may want to join the Block Protocol. But in addition, we can ask ourselves: How could they benefit if WordPress joins the Block Protocol?

This is my impression:

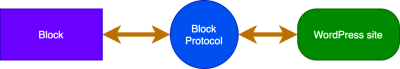

- Access to WordPress blocks

The most obvious answer is that all blocks currently available to WordPress (via the editor and FSE) will also be available for their own applications, whether they are based on WordPress or not. - Joining the community-led process to create blocks

Creating blocks is a time and effort-intensive process. It took the Gutenberg project 5 years to produce the Full Site Editor, and it is still a work in progress. And the number of people involved with any new release of WordPress is in the hundreds, with the latest one surpassing 600 contributors.

The WordPress community continuously invests plenty of resources in communication to make sure this process goes as smoothly as possible, even including retrospective meetings to analyze what went wrong, and improve it for the upcoming releases.

How many organizations can equal this well-polished process of managing hundreds of people to produce a common resource? For this reason, joining the effort led by the WordPress community to produce blocks, instead of going it alone, could benefit everyone. - A big adopter gives credibility and traction to the protocol

The Block Protocol has been barely released, and it’s still a draft. Who will use it? How will the project generate buy-in from potential stakeholders? Having WordPress backing it sends a strong signal and creates confidence for others to join by knowing that the project will have contributors and long-term support.

What’s In It For WordPress?

For WordPress to be relevant for the next 15 years, it needs to survive in the world of modern, highly dynamic applications. For that, starting from version 5.0 onward, WordPress has embarked on a modernization process, which has seen it metamorphosing from being a rather static application, rendering layouts based on PHP templates on the server-side to a still-static-but-less-so application which fetches data from a REST API, and uses JavaScript blocks to render content, and — since the latest version 5.9 — layouts.

Note: It is still not very dynamic, because the layouts are generated in advance in the wp-admin and saved to the DB, instead of generated on the client reacting to some action by the user.

This transformation has taken a while to materialize, starting all the way back in 2015 when Matt Mullenweg asked the WordPress community to “learn JavaScript deeply”. Joining the Block Protocol would be yet another stop on WordPress’s voyage of modernization.

Let’s see what benefits it could gain from it.

Keeping The Growth Of Its Market Share

As of today, WordPress powers 43% of all websites. While its success is undeniable, it is still not enough for Matt Mullenweg, who has expressed a desire for WordPress to reach 85% of market share. (Judging if this stance is right or wrong falls outside the scope of this article.)

Now, we can ask ourselves, what is exactly a WordPress site? In the past, with its monolithic PHP-based architecture, the response was quite clear. But nowadays we build websites based on a stack comprising multiple technologies. We may have a WordPress backend powering a React frontend, feeding it data via the WP REST API. Is that a WordPress site?

The answer is: I don’t know, but it possibly doesn’t matter either. If WordPress is one of the technologies in the stack, then it will keep growing. So far, WordPress could only assume the role of the CMS, managing the data to feed to the client. But now, thanks to the Block Protocol, WordPress could assume a new role: providing blocks to power the frontend of any application.

In this scenario, WordPress would take a bigger role in the creation of sites. Which would lead to WordPress still gaining market share, and becoming more entrenched in the web development toolkit, making it more difficult for it to ever become irrelevant.

Bigger Pool Of Contributors

By using the blocks offered by WordPress, developers who do not normally use WordPress will become acquainted with it, and, hopefully, appreciate it, and become contributors to the open-source code. This is important as the pool of contributors will get bigger (for instance, JavaScript has around 3 times as many professional developers as PHP does), and will bring a more diverse set of skills.

Further Availability Of Blocks

Needless to say, the block hub will work both ways: WordPress will make its blocks available to everyone else, but also blocks coded for somebody else will be available to power WordPress sites.

For instance, if Mailchimp decides to join as to use WordPress blocks to power its newsletter editor, and then it improves on them or produces and releases its own blocks, then these will be available to WordPress plugins that create and send newsletters.

Decoupling The WordPress Editor From Gutenberg

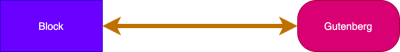

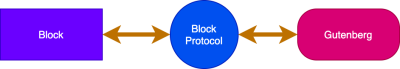

Gutenberg is the project that gives the foundation to the block editor in WordPress. It provides an engine that enables interacting with blocks. For instance, it takes the output from a block’s edit and save methods, as to render the HTML in the editor and save it to the DB.

However, the block editor needs not to be coupled to Gutenberg. After all, a “block” is a concept, and Gutenberg is a specific implementation. The Block Protocol can perfectly be placed in between them, acting as the link between the concept and the implementation.

As a result, now Gutenberg can be taken away, and any other implementation engine can take its place, providing a different experience that is still powered by the same blocks.

An interesting consequence is that WordPress can itself benefit from this architecture, because Gutenberg doesn’t live everywhere on the WordPress site, but only on the wp-admin. In other words, the public-facing site that we build using WordPress is itself not relying on Gutenberg; instead, it simply prints the HTML created with Gutenberg on the backend. That’s why I mentioned earlier on that WordPress sites are still not very dynamic.

By using the Block Protocol to communicate with blocks, we wouldn’t need to have Gutenberg on the client-side to use blocks. Instead, we could have a React application that renders the blocks directly and based on user interactions, making the site more dynamic.

The same idea can work in the wp-admin, in whatever page where Gutenberg is still not available (at least until it is). For instance, if we’d like to provide a settings page that is fully powered by blocks for our plugins, with the Block Protocol we could use React to render the needed configuration blocks (calendars, interactive maps, sliders, dropdowns with options, or any suitable input) and add a bit of PHP logic to save the data in the wp_optionstable.

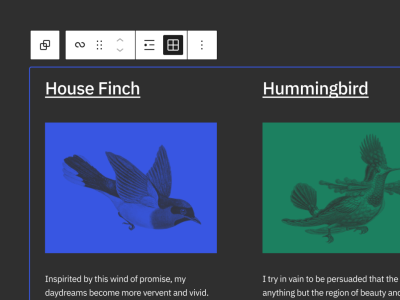

Embedding Blocks On The Public-Facing Site

Taking the previous section a bit further, the actual block could be embedded in the public-facing site for users to interact with it.

There are endless use cases for such a feature, including:

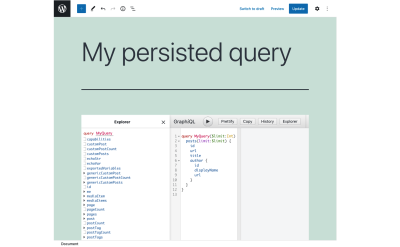

Another example comes from my own WordPress plugin, and being able to support it is the reason why I’m excited about the Block Protocol. The GraphQL API for WordPress ships with a GraphiQL client block which allows composing the GraphQL persisted query:

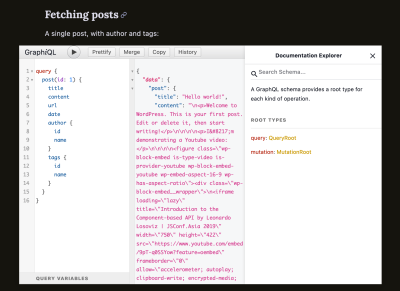

At the same time, I embed the GraphiQL client on the documentation site for visitors to play with it and discover how the GraphQL server works:

With the Block Protocol, this idea of exposing the GraphiQL client on the documentation site could also be granted to the users of my plugin. Then, they could simply embed the GraphiQL block on their own public-facing sites to document how to retrieve data from their own GraphQL APIs for their own visitors.

Aiding In Gutenberg’s “Collaboration” Phase

Being able to embed blocks on the public-facing site could also be useful for phase 3 of the block editor, which aims to streamline collaboration to produce a co-authoring experience similar to Google Docs or Dropbox Paper.

When I receive a link to Dropbox Paper, I don’t need to be logged in to visualize its contents:

Similarly, we could have a client-side that is able to render and interact with blocks, so that users who are not logged in can also provide feedback. These visitors would not need to access the wp-admin of the site, so we will be maximizing the opportunities for collaboration.

Further Improving The “Single API For Everything” Concept

The block concept was introduced as a way to unify all the different ways to add content on the WordPress site. In the past, when using the “classic” editor, we could add dynamic code via a widget or a shortcode, and manipulate the appearance of the site via the customizer. The block replaces all of these different mechanisms by providing a “single API” to produce and customize all the content on the site.

This simplification has happened in the UI. However, blocks themselves don’t always provide a single way to deal with them, since dynamic blocks require the same output to be rendered in JavaScript and PHP (the former one to render the HTML for the editor, the latter one to print it in the public-facing site). This situation is a cause of angst for developers, and adds barriers for new contributors.

There have been several proposals to address this issue (brilliantly summarized in this discussion), but none of them is convincing enough. The WooCommerce plugin has also dealt with a similar concern, but its solution seems (to me) a bit complicated. A mechanism to create DRY code should ideally be provided by the CMS without the need for hacks.

The Block Protocol could provide a better alternative. If the developer doesn’t want to code the same logic again in PHP, the rendering of the block could instead be done on the frontend by using the same block. This would be based on client-side rendering (CSR) instead of server-side rendering (SSR) which is not always recommended (as it may impact the indexing of content by search engines), but the option to decide for either of them would rest on the developer.

As a side benefit, this solution could also entice more React developers to use WordPress.

Using Developments From Outside The WordPress Realm

As I mentioned earlier, adhering to a shared protocol could lead to non-coordinated developments that produce a rich ecosystem, as it has happened with GraphQL.

For instance, SpectaQL is a documentation generator for GraphQL APIs. Just by adhering to the GraphQL specification this project allows the API to be automatically documented, requiring very little effort from the developer.

Adhering to the Block Protocol could produce similar effects. We can foresee that some projects may automatically extract the information from block-metadata.json, and produce a static site documenting all the blocks. This same idea is currently being implemented for Gutenberg. If some project already addressed this job for the Block Protocol, Gutenberg could piggyback ride on it, and free up its contributors to handle other tasks.

Improved Support For GraphQL

The other reason that particularly excites me, is that the GraphQL servers for WordPress (WPGraphQL and my own GraphQL API for WordPress) currently cannot provide optimal support for Gutenberg, because block.json does not declare the actual type of an object or array property. For instance, a block in Gutenberg may declare a property to be of type array, but GraphQL needs to know it is an array of type String.

The Block Protocol strongly encourages to define the ultimate type of the property:

Where available, blocks SHOULD expect and handle an

entityTypesfield containing entity type definitions for any entities sent to the blocks.

Hence, if WordPress blocks adhered to the Block Protocol, their JSON schema would be upgraded to provide this information, and the GraphQL plugins would then be able to retrieve block data without resorting to hacks.

Wrapping Up

In this article, I’ve discussed some potential consequences of WordPress joining the Block Protocol, suggesting that it will produce positive outcomes. However, I have not touched upon how feasible it is for it to happen.

Is it technically possible? Can it be done without breaking backward compatibility? Do the potential benefits outweigh the effort required? Does it even make sense for a Block Protocol to exist in the first place or different requirements by different applications cannot be reconciled at the block level?

All these questions (and many others) need to have a response before the decision to join the Block Protocol or not is taken. As Matt Mullenweg has expressed his interest, it is now time for the community to weigh in and decide whether WordPress should stop and refuel in this new port on its modernization journey, or skip it and continue sailing forward.