Have you ever experienced the frustration of trying to tap a button on a mobile device only to have it do nothing because the target size is just not large enough **and it’s not picking up on your press? Maybe you have larger fingers, like I do, or maybe it’s due to limited dexterity. This is because the sadly ever-decreasing target area of elements we, the users, have to interact with.

Let’s talk about target size and how to make it large enough for users to easily interact with an element. This is an especially big deal if a user is accessing content on a small hand-held touch screen device where real estate is much tighter.

Success criterion revisited

I touched (no pun intended) on Success Criterion in a previous article covering the WCAG 2.1 criterion, Label in Name. In short, the WCAG criteria is the baseline from which we determine whether our work is “accessible.”

If you’re wondering whether there’s a criterion for target size, the answers is yes. It’s WCAG 2.5.5. Pulling straight from the guidelines. passing WCAG 2.5.5 with a AAA grade requires “the size of the target for pointer inputs is at least 44 by 44 CSS pixels except when:

- Equivalent: The target is available through an equivalent link or control on the same page that is at least 44×44 CSS pixels;

- Inline: The target is in a sentence or block of text;

- User Agent Control: The size of the target is determined by the user agent and is not modified by the author;

- Essential: A particular presentation of the target is essential to the information being conveyed.”

What could possibly go wrong?

It’s just a size, right? Easy peasy. Nothing can possibly go awry.

Or can it?

Small target sizes can cause accessibility hurdles for many people. Have you ever been traveling in a vehicle on a bumpy road and you’re trying to interact with an app on your mobile can not press on an element? That is an accessibility hurdle. Those with motor skill or cognitive impairments will have a much harder time because it is much harder for them if the target size is too small and does not meet WCAG requirements.

I don’t mean to pick on Twitter here, but it’s the first notable example I found while hunting for examples of small targets.

Imagine the hurdles someone with neuromuscular disorders, such as Multiple Sclerosis, Cerebral Palsy, arthritis, tremors, or Alzheimer’s Disease or any other motor impairment would have to overcome to activate a target in any of those cases.

Another favorite example I see quite often? Ads. Have you ever struggled to click the minuscule “X” button to close them?

Having no motor skill or cognitive disabilities personally, I find myself fumbling around and taking multiple times to hit some target areas. The fact that someone who needs to use something like a pen or stylus on a target size that is not a minimum of 44×44 pixels can be a difficult task. These targets shouldn’t need multiple attempts to activate when the target size doesn’t meet recommended guidelines.

Target size considerations

WCAG 2.5.5 goes into specific detail to help us account for these things by defining the four types of controls we just saw: equivalent, inline, User Agent, and essential.

We’re going to look at different considerations for determining target sizes and hold them up next to the WCAG guidelines to help steer us toward making good, accessible design decisions.

Consider the difference between “click” and “tap”

This success criteria ensures that target sizes are large enough for users to easily activate targets, even if the user is accessing these targets on handheld devices. We typically associate small screens with “taps” instead of “clicks” when it comes to activating targets. And that’s something we need to consider in our target sizing.

Mice and similar input devices use a pointer on the screen, which is considered “fine” precision because it allows a user to access an element on the screen with exact precision. Fine precision makes it easier to access smaller target sizes in theory. The trouble is, that sort of input device can be tough for some users, whether it’s with gripping the device, or some other cognitive or motor skill. So, even with fine precision, having a clear target is still a benefit.

Touch, on the other hand, can be problematic as it is an input mechanism with very “coarse” precision. Users can lack a level of fine control when using a mouse or stylus, for example. A finger, which is larger than a mouse pointer, generally obstructs a user’s view of the exact location on the screen that is being activated or touched. Hence, “course” precision.

This issue is exacerbated in responsive design, which needs to accommodate for numerous types of fine and coarse inputs. Both input types must be supported for a site that can be accessed by a desktop or laptop with a mouse, as well as a mobile device or tablet with a touch screen.

That makes the actual size we use for a target a pretty important detail. Depending on who is using a control, what that control does, how often it’s used, and where it’s located, we ought to consider using larger, clearer targets to prevent things like unintended actions.

But with all this said, we do actually have a CSS media query that can detect a pointer device so we can target certain styles to either fine or coarse input interactions, and it’s well-supported. Here’s an example pulled right out of the spec:

/* Make radio buttons and check boxes larger if we have an inaccurate primary pointing device */

@media (pointer: coarse) { input[type="checkbox"], input[type="radio"] { min-width: 30px; min-height: 40px; background: transparent; }

}But wait. While this is great and all, Patrick H. Lauke offers a word of caution about this interaction media query and it’s potential for making incorrect assumptions.

Consider that different platforms have different requirements

When WCAG specifies exact values, it’s worth paying attention. Notice that we’re advised to make target sizes at least 44×44 pixels, which is mentioned no fewer than 18 times in the WCAG 2.5.5 explainer.

However, you may have also seen similar requirements with different guidance from the likes of Apple’s “Human Interface Guidelines” for iOS, and Google’s “Material Design” in their platform design requirements.

(Material Design, “Accessibility”)

Consider the “tappable area” of a target

Notice that Apple’s platform requirements refer to a “tappable area” when describing the ideal target size. That means that we’re talking about space as much as we are about the appearance of a target. For example, Google’s Material Design suggests at least a 48×48 dp (density-independent pixels) target size for interactive elements. But what if your design requirements call for a 24×24 dp icon? It’s totally legit to use padding in our favor to create more interactive space around the icon, comprising the 48×48 dp target size. Or, as it’s documented in Material Design:

Touch targets are the parts of the screen that respond to user input. They extend beyond the visual bounds of an element. For example, an icon may appear to be 24×24 dp, but the padding surrounding it comprises the full 48×48 dp touch target.

Consider responsive layout behavior

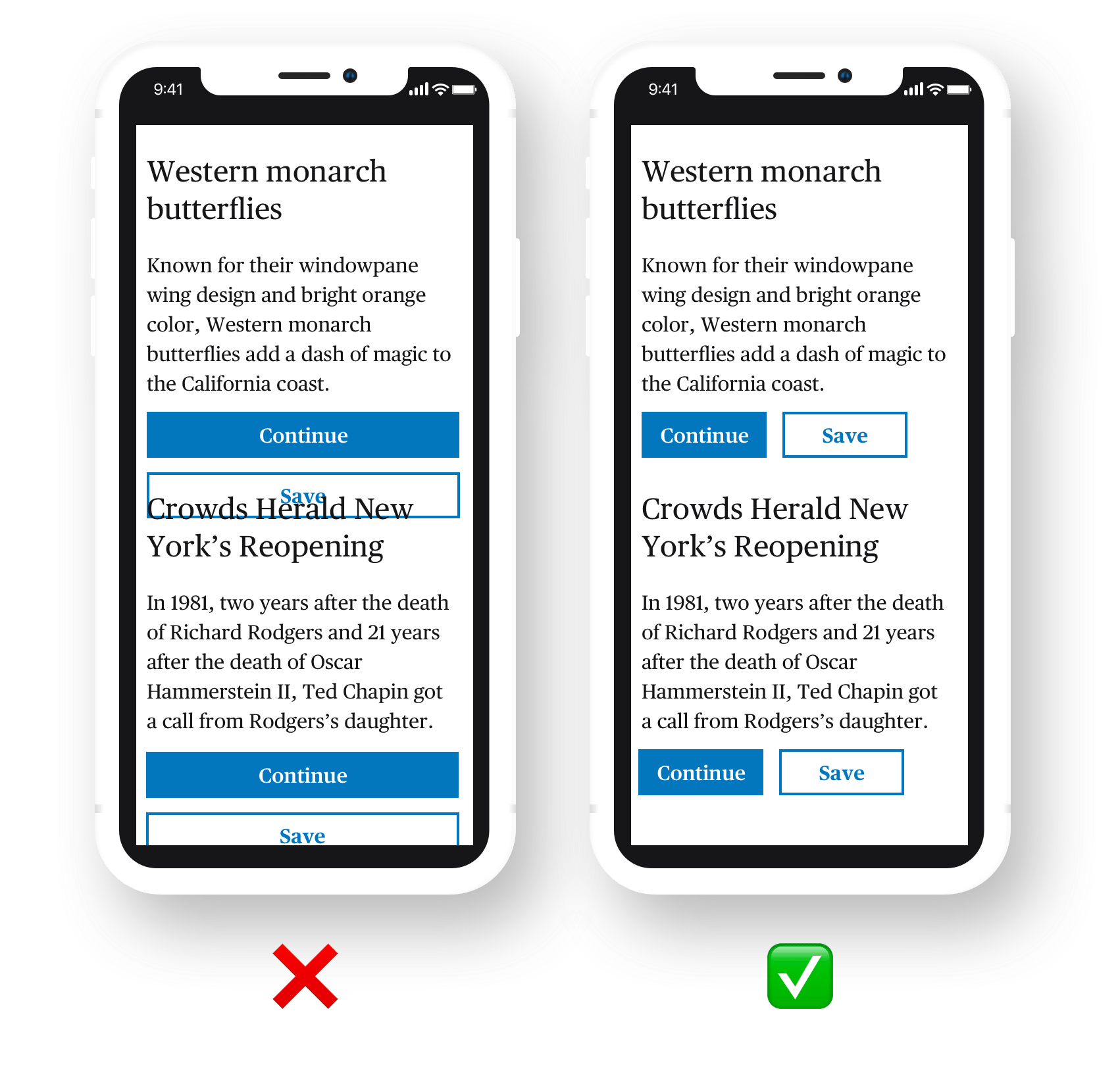

That’s right, we’ve gotta consider how things shift and move around in a design that’s meant to respond to different viewport sizes. One example might be buttons that stack on small screens but are inline on larger screen. We want to make sure that transition accounts for the placement of surrounding elements in order to prevent overlapping elements or targets.

Speaking of inline, there’s a particular piece of the WCAG’s exception for inline targets that’s worth highlighting:

Inline: Content displayed can often be reflowed based on the screen width available (responsive design). In reflowed content, the targets can appear anywhere on a line and can change position based on the width of the available screen. Since targets can appear anywhere on the line, the size cannot be larger than the available text and spacing between the sentences or paragraphs, otherwise the targets could overlap. It is for this reason targets which are contained within one or more sentences are excluded from the target size requirements.

(Emphasis mine)

Now, we’re not necessarily talking about buttons that are side-by-side here. We can links within text and that text might break the target’s placement, possibly into two lines.

Consider the target’s relationship to its surroundings

We just saw how inline links within a block of text are exempt from the 44×44 rule. There are similar exceptions depending on the target’s relationship to the elements around it.

Let’s take the example that the WCAG explainer provides, again, in it’s description of inline target exceptions:

If the target is the full sentence and the sentence is not in a block of text, then the target needs to be at least 44 by 44 CSS pixels.

That’s a good one. We ought to consider whether the target is its own block or part of a larger block of text. If the target is its own block, then it needs to abide by the rules, whether it’s a button with a short label, or a complete sentence that’s linked up. On the flip side, a complete sentence that’s linked up inside another block of text doesn’t have to meet the target size requirements.

You might think that something like a linked icon at the end of a sentence or paragraph would need to play by the rules, but the WCAG is clear that these targets are exempt:

A footnote or an icon within or at the end of a sentence is considered to be part of a sentence and therefore are excluded from the minimum target size.

And that makes sense. Imagine content with a line height of, say 32 pixels and an icon at the end that’s all padded up to be 44×44 pixels and how easy it would be to inadvertently activate the icon.

Consider whether the target is styled by the User Agent

If the target is completely un-styled — in the sense that you’ve added no CSS to it — and instead takes on the default styles provided by the browser, then there’s no need to stress the 44×44 rule. That makes sense. The User Agent is like system-level UI so changing it superficially with our own styles would be overriding an entire system which could lead to inconsistencies in that UI.

So, yeah, if you’re rockin’ a default <button> or the like, and there are no other styles or sizing applied to it, then it’s good to go. But lots of us use resets to normalize UI elements across browsers, so watch for that in your codebase because that’s going to affect the User Agent styles of your target.

Consider if there are other ways to activate the functionality

We’ve all used in-page anchor links, right? Heck, CSS-Tricks often has a table of contents at the top of an article that’s merely a list of anchor links.

WCAG actually uses anchor links as an example of something that’s off the hook as far as meeting the target size requirements. Why? Because it’s just as possible to manually scroll down to a specific location on a page as it is to click a link to jump there. There are two ways to accomplish the same thing, and one of those ways is built right into the browser.

But we still ought to use care when working with something like a table of contents. I’m not entirely clear here, but given that a table of contents is list of links, each link may very well constitute its own block of text that’s not part of a larger block of a text, like a paragraph. So, in this sort of case, maybe a little extra space between list items is still a good idea. There’s less change of accidentally clipping or tapping two or more targets at once.

Wrapping up

WCAG 2.5.5 criterion provides guidance for applying target sizes that are clear, unobstructed, and easy to activate. As we saw, there are plenty of cases where the size of a target can make all the difference in the world when it comes to completing an action.

The interesting thing about the target size guidelines is what is exempted from them. While we didn’t cover each specific exemption on its own, we did look at a bunch situations that require careful consideration for sizing a target, from the type of input device that’s in use to the relationship of the target to its surrounding elements, and plenty of things between.

The key to accessible target sizing isn’t necessary about using less styling on a target (although we did see that default User Agent styles are exempt), but rather having context and styling accordingly. There are probably dozens more situations we could have covered here and examined how styles come into play — so if you have some, share!

And as far as styling goes, CSS specifications have specific features, like the interation media query for pointer, to make target sizing even better for people. Used well, it could be a great way to detect if a visitor is using a fine or course input device. That way, we can tailor things to make their experience better than if we treated those differences the same.

So, yes, target sizes are an easy thing to brush off and ignore. But hopefully now you’re like me and have a genuine appreciation for targets that are correctly sized now that you have the information to make correctly sized targets of your own.

The post Looking at WCAG 2.5.5 for Better Target Sizes appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

You can support CSS-Tricks by being an MVP Supporter.