I have recently been interested in the difference of opinions between the different browser vendors about the future of the web — specifically in the various efforts to push web platform capabilities closer to native platforms, such as Chromium’s Project Fugu.

The main positions can be summarized as:

- Google (together with partners like Intel, Microsoft and Samsung) is aggressively pushing forward and innovating with a plethora of new APIs like the ones in Fugu, and ships them in Chromium;

- Apple is pushing back with a more conservative approach, marking many of the new APIs as raising security & privacy concerns;

- This (together with Apple’s restrictions on browser choice in iOS) has created a stance labeling Safari to be the new IE while claiming that Apple is slowing down the progress of the web;

- Mozilla seems closer to Apple than to Google on this.

My intention in this article is to look at claims identified with Google, specifically ones in the Platform Adjacency Theory by Project Fugu leader Alex Russell, look at the evidence presented in those claims, and perhaps reach my own conclusion.

Specifically, I intend to dive into WebUSB (a particular controversial API from Project Fugu), check whether the security claims against it have merit, and try to see if an alternative emerges.

The Platform Adjacency Theory

The aforementioned theory makes the following claims:

- Software is moving to the web because it is a better version of computing;

- The web is a meta-platform — a platform abstracted from its operating system;

- The success of a meta-platform is based on it accomplishing the things we expect most computers to do;

- Declining to add adjacent capabilities to the web meta-platform on security grounds, while ignoring the same security issues in native platforms, will eventually make the web less and less relevant;

- Apple & Mozilla are doing exactly that — declining to add adjacent computing capabilities to the web, thus “casting the web in amber”.

I relate with the author’s passion for keeping the open web relevant, and with the concern that going too slow with enhancing the web with new features will make it irrelevant. This is augmented by my dislike of app stores and other walled gardens. But as a user I can relate to the opposite perspective — I get dizzy sometimes when I don’t know what websites I’m browsing are capable or not capable of doing, and I find platform restrictions and auditing to be comforting.

Meta-Platforms

To understand the term “meta-platform”, I looked at what the theory uses that name for — Java and Flash, both products of the turn of the millennium.

I find it confusing to compare either Java or Flash to the web. Both Java and Flash, as mentioned in the theory, were widely distributed at the time through browser plug-ins, making them more of an alternative runtime riding on top of the browser platform. Today, Java is used mainly in the server and as part of the Android platform, and both do not share much in common, except the language.

Today server-side Java is perhaps a meta-platform, and node.js is also a good example of a server-side meta-platform. It’s a set of APIs, a cross-platform runtime, and a package ecosystem. Indeed node.js is always adding more capabilities, previously only possible as part of a platform.

On the client side, Qt, a C++-based cross-platform framework, does not come with a separate runtime, it’s merely a (good!) cross-platform library for UI development.

The same applies for Rust — it’s a language and a package manager, but does not depend on pre-installed runtimes.

The other ways to develop client-side applications are mainly platform-specific, but also include some cross-platform mobile solutions like Flutter and Xamarin.

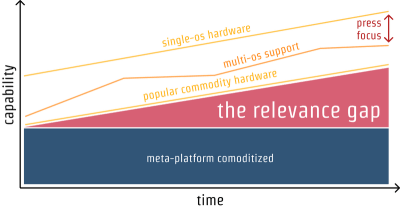

Capabilities vs. Time

The main graph in the theory, shows the relevance of meta-platforms on a 2D axis of capabilities vs. time:

I can see how the above graph makes sense when talking about cross-platform development frameworks mentioned above like Qt, Xamarin, Flutter and Rust, and also to server platforms like node.js and Java/Scala.

But all of the above have a key difference from the web.

The 3rd Dimension

The meta-platforms mentioned earlier are indeed competing against their host OSes in the race for capabilities, but unlike the web, they are not opinionated about trust and distribution — the 3rd dimension, that in my opinion is missing in the above graph.

Qt and Rust are good ways to create apps that are distributed via WebAssembly, downloaded and installed directly on the host OS, or administered through package managers like Cargo or Linux distributions like Ubuntu. React Native, Flutter and Xamarin are all decent ways to create apps that are distributed via app stores. node.js and Java services are usually distributed via a docker container, a virtual machine, or some other server mechanism.

Users are mostly unaware of what was used to develop their content, but are aware to some degree of how it is distributed. Users don’t know what Xamarin and node.js are, and if their Swift App was replaced one day by a Flutter App, most users wouldn’t and ideally shouldn’t care about it.

But users do know the web — they know that when they’re “browsing” in Chrome or Firefox, they are “online” and can access content they don’t necessarily trust. They know that downloading software and installing it is a possible hazard, and might be blocked by their IT administrator. In fact, it’s important for the web platform that users know that they’re currently “browsing the web”. That’s why, for example, switching to full-screen mode shows a clear prompt to the user, with instructions of how to get back from it.

The web has become successful because it’s not transparent — but clearly separated from its host OS. If I can’t trust my browser to keep random websites away from reading files on my hard-drive, I probably wouldn’t go to any website.

Users also know that their computer software is “Windows” or “Mac”, whether their phones are Android or iOS-based, and whether they’re currently using an app (when on iOS or Android, and on Mac OS to some degree). The OS and the distribution model are generally known to the user — the user trusts their OS and the web to do different things, and to different degrees of trust.

So, the web cannot be compared to cross-platform development frameworks, without taking its unique distribution model into account.

On the other hand, web technologies are also used for cross-platform development, with frameworks like Electron and Cordova. But those are not exactly “the web”. When compared to Java or node.js, The term “The web” needs to be substituted with “Web Technologies”. And “web technologies” used in this way don’t necessarily need to be standard-based or work on multiple browsers. The conversation about Fugu APIs is somewhat tangential to Electron and Cordova.

Native Apps

When adding capabilities to the web platform, the 3rd dimension — the trust and distribution model — cannot be ignored, or taken lightly. When the author claims that “Apple and Mozilla posturing about risks from new capabilities is belied by accepted extant native platform risks”, he is putting the web and native platforms in the same dimension in regards to trust.

Granted, native apps have their own security issues and challenges. But I don’t see how that’s an argument in favor of more web capabilities, like here. This is a fallacy — the conclusion should be fixing security issues with native apps, not relaxing security for web apps because they’re in a relevance catch-up game with OS capabilities.

Native and web cannot be compared in terms of capabilities, without taking the 3rd dimension of trust and distribution model into account.

App Store Limitations

One of the criticisms about native apps in the theory is about lack of browser engine choice on iOS. This is a common thread of criticism against Apple, but there is more than one perspective to this.

The criticism is specifically about Item 2.5.6 of Apple’s app store review guidelines:

“Apps that browse the web must use the appropriate WebKit framework and WebKit JavaScript.”

This might seem anti-competitive, and I do have my own reservation about how restrictive iOS is. But item 2.5.6 cannot be read without the context of the rest of the app-store review guidelines, for example Item 2.3.12:

“Apps must clearly describe new features and product changes in their ‘What’s New’ text.”

If an app could receive device access permissions, and then included its own framework that could execute code from any web site out there, those items in the app store review guidelines would become meaningless. Unlike apps, web sites don’t have to describe their features and product changes with every revision.

This becomes an even bigger problem when browsers ship experimental features, like the ones in project Fugu, which are not yet considered a standard. Who defines what a browser is? By allowing apps to ship any web framework, the app store would essentially allow the “app” to run any unaudited code, or change the product completely, circumventing the store’s review process.

As a user of both web sites and apps, I think both of them have space in the computing world, although I hope as much as possible could move to the web. But when considering the current state of web standards, and how the dimension of trust and sandboxing around things like Bluetooth and USB is far from being solved, I don’t see how allowing apps to freely execute content from the web would be beneficial for users.

The Pursuit Of Appiness

In another related blog post, the same author addresses some of this, when speaking about native apps:

“Being ‘an app’ is merely meeting a set of arbitrary and changeable OS conventions.”

I agree with the notion that the definition of “app” is arbitrary, and that its definition relies on whoever defines the app store policies. But today, the same is true for browsers. The claim from the post that web applications are safe by default is also somewhat arbitrary. Who draws the line in the sand of “what is a browser”? Is the Facebook app with a built-in browser “a browser”?

The definition of an app is arbitrary, but also important. The fact that every revision of an application using low-level capabilities is audited by someone that I might trust, even if that someone is arbitrary, makes apps what they are. If that someone is the manufacturer of the hardware I’ve paid for, it makes it even less arbitrary — the company that I’ve bought my computer from is the one auditing software with lower capabilities to that computer.

Everything Can Be A Browser

Without drawing a line of “what’s a browser”, which is what the Apple app store essentially does, every app could ship its own web engine, lure the user to browse to any website using its in-app browser, and add whatever tracking code it wants, collapsing the 3rd dimension difference between apps and websites.

When I use an app on iOS, I know my actions are currently exposed to two players: Apple & the identified app manufacturer. When I use a website on Safari or in a Safari WebView, my actions are exposed to Apple & to the owner of the top-level domain of the web site I’m currently viewing. When I use an in-app browser with an unidentified engine, I am exposed to Apple, the manufacturer of the app, and to the owner of the top-level domain. This can create avoidable same-origin violations, such as the owner of the app tracking all of my clicks on foreign websites.

I agree that perhaps the line in the sand of “Only WebKit” is too harsh. What would be an alternative definition of a browser that wouldn’t create a backdoor for tracking user browsing?

Other Criticism About Apple

The theory claims that Apple’s decline to implement features is not limited to privacy/security concerns. It includes a link, which does indeed show a lot of features that are implemented in Chrome and not in Safari. However, when scrolling down, it also lists a sizable amount of other features that are implemented in Safari and not in Chrome.

Those two browser projects have different priorities, but it’s far from the categorical statement “The game becomes clear when zooming out” and from the harsh criticism about Apple trying to cast the web in amber.

Also, the links titled it’s hard and we don’t want to try lead to Apple’s statements that they would implement features if security/privacy concerns were met. I feel that putting these links with those titles is misleading.

I would agree with a more balanced statement, that Google is a lot more bullish than Apple about implementing features and advancing the web.

Permission Prompt

Google goes long innovative ways in the 3rd dimension, developing new ways to broker trust between the user, the developer and the platform, sometimes with great success, like in the case of Trusted Web Activities.

But still, most of the work in the 3rd dimension as it relates to device APIs is focused around permission prompts and making them more scary, or things like time-box permission grants, and block-listed domains.

“Scary” prompts, like the ones in this example we see from time to time, look like they are meant to discourage people from going to pages that seem potentially malicious. Because they’re so blatant, those warnings encourage developers to move to safer APIs and to renew their certificates.

I wish that for device-access capabilities we could come up with prompts that encourage engagement and ensure that the engagement is safe, rather than discourage it and transfer the liability to the user, with no remediation available for the web developer. More on that later.

I do agree with the argument that Mozilla & Apple should at least try to innovate in that space rather than “decline to implement”. But maybe they are? I think isLoggedIn from Apple, for example, is an interesting and relevant proposal in the 3rd dimension that future device APIs could build upon — for example, device APIs that are fingerprinting-prone can be made available when the current website already knows the identity of the user.

WebUSB

In the next section I will dive into WebUSB, check what it allows, and how it’s handled in the 3rd dimension — what is the trust and distribution model? Is it sufficient? What are the alternatives?

The Premise

The WebUSB API allows full access to the USB protocol for device-classes that are not block-listed.

It can achieve powerful things like connecting to an Arduino board or debugging and Android phone.

It’s exciting to see Suz Hinton’s videos on how this API can help achieve things that were very expensive to achieve before.

I truly wish platforms found ways to be more open and allow quick iterations on educational hardware/software projects, as an example.

Funny Feeling

But still, I get a funny feeling when I look at what WebUSB enables, and the existing security issues with USB in general.

USB feels too powerful as a protocol exposed to the web, even with permission prompts.

So I’ve researched further.

Mozilla’s Official View

I started by reading what David Baron had to say about why Mozilla ended up rejected WebUSB, in Mozilla’s official standards position:

“Because many USB devices are not designed to handle potentially-malicious interactions over the USB protocols and because those devices can have significant effects on the computer they’re connected to, we believe that the security risks of exposing USB devices to the Web are too broad to risk exposing users to them or to explain properly to end users to obtain meaningful informed consent.”

The Current Permission Prompt

This is what Chrome’s WebUSB permission prompt looks like at the time of publishing this post:

Particular domain Foo wants to connect to particular device Bar. To do what? and how can I know for sure?

When granting access to the printer, camera, microphone, GPS, or even to a few of the more contained WebBluetooth GATT profiles like heart rate monitoring, this question is relatively clear, and focuses on the content or action rather than on the device. There is a clear understanding of what information I want from the peripheral or what action I want to perform with it, and the user-agent mediates and makes sure that this particular action is handled.

USB Is Generic

Unlike the devices mentioned above that are exposed via special APIs, USB is not content-specific. As mentioned in the intro of the spec, WebUSB goes further and is intentionally designed for unknown or not-yet-invented types of devices, not for well-known device classes like keyboards or external drives.

So, unlike the cases of the printer, GPS and camera, I cannot think of a prompt that would inform the user of what granting a page permission to connect to a device with WebUSB would allow in the content realm, without a deep understanding of the particular device and auditing the code that’s accessing it.

The Yubikey Incident And Mitigation

A good example from not too long ago is the Yubikey incident, where Chrome’s WebUSB was used to phish data from a USB-powered authentication device.

Since this is a security issue that is said to be resolved, I was curious to dive into Chrome’s mitigation efforts in Chrome 67, which include blocking a specific set of devices and a specific set of classes.

Class/Device Block-List

So Chrome’s actual defense against WebUSB exploits that happened in the wild, in addition to the currently very general permission prompt, was to block specific devices and device classes.

This may be a straightforward solution for a new technology or experiment, but will become harder and harder to accomplish when (and if) WebUSB becomes more popular.

I’m afraid that the people innovating on educational devices via WebUSB might reach a difficult situation. By the time they’re done prototyping, they could be facing a set of ever-changing non-standard block lists, that only update together with browser versions, based on security issues that have nothing to do with them.

I think that standardizing this API without addressing this will end up being counterproductive to the developers relying on it. For example, someone could spend cycles developing a WebUSB application for motion detectors, only to find out later that motion detectors become a blocked class, either due to security reasons or because the OS decides to handle them, causing their entire WebUSB effort to go to waste.

Security vs. Features

The platform adjacency theory, in some ways, considers capabilities and security to be a zero-sum game, and that being too conservative on security & privacy concerns would cause platforms to lose their relevance.

Let’s take Arduino as an example. Arduino communication is possible with WebUSB and is a major use case. Someone developing an Arduino device will now have to consider a new threat scenario, where a site tries to access their device using WebUSB (with some user permission). As per the spec, this device manufacturer now has to “design their devices to only accept signed firmware”. This can add burden to firmware developers, and increase development costs, while the whole purpose of the spec is to do the opposite.

What Makes WebUSB Different From Other Peripherals

In browsers, there is a clear distinction between user interactions and synthetic interactions (interactions instantiated by the web page).

For example, a web page can’t decide on its own to click a link on or wake up the CPU/display. But external devices can — for example, a mouse device can click a link on behalf of the user and almost any USB device can wake up the CPU, depending on the OS.

So even with the current WebUSB specification, devices can choose to implement several interfaces, e.g. debug for adb and HID for pointer input, and using malicious code that takes advantage of ADB, become a keylogger and browse websites on behalf of the user, given the right exploitable firmware flashing mechanism.

Adding that device to a blocklist would be too late for devices with firmware that was compromised using ADB or other allowed forms of flashing, and would make device manufacturers even more reliant than before on browser versions for security fixes associated with their devices.

Informed Consent & Content

The problem with informed consent and USB, as mentioned before, is that USB (specifically in the extra-generic WebUSB use-cases) is not content-specific. Users know what a printer is, what a camera is, but “USB” for most users is merely a cable (or a socket) — a means to an end — very few users know that USB is a protocol and what enabling it between websites and devices means.

One suggestion was to have a “scary” prompt, something along the lines of “Allow this web page to take over the device” (which is an improvement over the seemingly harmless “wants to connect”).

But as scary as prompts get, they cannot explain the breadth of possible things that can be done with raw access to a USB peripheral that the browser doesn’t know intimately, and if they did, no user in their right mind would click “Yes”, unless it’s a device that they fully trust to be bug-free and a website they truly trust to be up-to-date and not malicious.

A possible prompt like that would read “Allow this web page to potentially take over your computer”. I don’t think that a scary prompt like this one would be beneficial for the WebUSB community, and constant changes to these dialogs will leave the community confused.

Prototyping vs. Product

I can see a possible exception to this. If the premise of WebUSB and the other project Fugu APIs was to support prototyping rather than product-grade devices, all-encompassing generic prompts could make sense.

In order to make that viable, though, I think the following must happen:

- Use language in the specs that set expectations about this being for prototyping;

- Have these APIs available only after some opt-in gesture, like having the user enable them manually in the browser settings;

- Have “scary” permission prompts, like the ones for invalid SSL certificates.

Not having the above makes me think that these APIs are for real products rather than for prototypes, and as such, the feedback holds.

An Alternative Proposal

One of the parts in the original blog post that I agree with is that it’s not enough to say “no” — major players in the web world who decline certain APIs for being harmful should also play offense and propose ways in which these capabilities that matter to users and developers can be safely exposed. I don’t represent any major player, but I’m going to give it a humble go.

I believe that the answer to this lies in the 3rd dimension of trust and relationship, and that it’s outside the box of permission prompts and block-lists.

Straightforward And Verified Prompt

The main case I’m going to make is that the prompt should be about the content or action, and not about the peripheral, and that informed consent can be granted for a specific straightforward action with a specific set of verified parameters, not for a general action like “taking over” or “connecting to” a device.

The 3D Printer Example

In the WebUSB spec, 3D printers are brought as an example, so I’m going to use it here.

When developing a WebUSB application for a 3D printer, I want the browser/OS prompt to ask me something along the lines of Allow AutoDesk 3ds-mask to print a model to your CreatBot 3D printer?, be shown a browser/OS dialog with some print parameters, like refinement, thickness and output dimensions, and with a preview of what’s going to be printed. All of these parameters should be verified by a trusted user agent, not by a drive-by web page.

Currently, the browser doesn’t know the printer, and it can verify only some of the claims in the prompt:

- The requesting domain has a certificate registered to AutoDesk, so there is some certainty that this is AutoDesk Inc;

- The requested peripheral calls itself “CreatBot 3d printer”;

- This device, device class and domain are not found in the browser’s block-lists;

- The user responded “Yes” or “No” to a general question they were asked.

But in order to show a truthful prompt and dialog with the above details, the browser would also have to verify the following:

- When permission is granted, the action performed will be printing a 3D model, and nothing but that;

- The selected parameters (refinement/thickness/dimensions etc.) are going to be respected;

- A verified preview of what is going to be printed was shown to the user;

- In certain sensitive cases, an additional verification that this is in fact AutoDesk, maybe with something like a revokable short-lived token.

Without verifying the above, a website that was granted permission to “connect to” or “take over” a 3D printer can start printing huge 3D models due to a bug (or malicious code in one of its dependencies).

Also, an imagined full-blown web 3D printing capability would do a lot more than what WebUSB can provide — for example, spooling and queuing different print requests. How would that be handled if the browser window is closed? I haven’t researched all the possible WebUSB peripheral use-cases, but I’m guessing that when looking at them from a content/action perspective, most will need more than USB access.

Because of the above, using WebUSB for 3D printing will probably be hacky and short-lived, and developers relying on it will have to provide a “real” driver for their printer at some point. For example, if OS vendors decide to add built-in support for 3D printers, all sites using that printer with WebUSB would stop working.

Proposal: Driver Auditing Authority

So, overarching permissions like “take over the peripheral” are problematic, we don’t have enough information in order to show a full-fledged parameter dialog and verify that its results are going to be respected, and we don’t want to send the user on an unsafe trip to download a random executable from the web.

But what if there was an audited piece of code, a driver, that used the WebUSB API internally and did the following:

- Implemented the “print” command;

- Displayed an out-of-page print dialog;

- Connected to a particular set of USB devices;

- Performed some of its actions when the page is in the background (e.g. in a service worker), or even when the browser is closed.

An auditing of a driver like this can make sure that what it does amounts to “printing”, that it respects the parameters, and that it shows the print preview.

I see this as being similar to certificate authorities, an important piece in the web ecosystem that is somewhat disconnected from the browser vendors.

Driver Syndication

The drivers don’t have to be audited by Google/Apple, though the browser/OS vendor can choose to audit drivers on its own. It can work like SSL certificate authorities — the issuer is a highly trusted organization; for example, the manufacturer of the particular peripheral or an organization that certifies many drivers, or a platform like Arduino. (I imagine organizations popping up similar to Let’s Encrypt.)

It might be enough to say to users: “Arduino trusts that this code is going to flash your Uno with this firmware” (with a preview of the firmware).

Caveats

This is of course not free of potential problems:

- The driver itself can be buggy or malicious. But at least it’s audited;

- It’s less “webby” and generates an additional development burden;

- It doesn’t exist today, and cannot be solved by internal innovation in browser engines.

Other Alternatives

Other alternatives could be to somehow standardize and improve the cross-browser Web Extensions API, and make the existing browser add-on stores like Chrome Web Store into somewhat of a driver auditing authority, mediating between user requests and peripheral access.

Summary Of Opinion

The author, Google and partners’ bold efforts to keep the open web relevant by enhancing its capabilities are inspirational.

When I get down to the details, I see Apple and Mozilla’s more conservative view of the web, and their defensive approach to new device capabilities, as carrying technical merit. Core issues with informed consent around open-ended hardware capabilities are far from being solved.

Apple could be more forthcoming in the discussion to find new ways to enable device capabilities, but I believe this comes from a different perspective about computing, a standpoint that was part of Apple’s identity for decades, not from an anti-competitive standpoint.

In order to support things like the somewhat open-ended hardware capabilities in project Fugu, and specifically WebUSB, the trust model of the web needs to evolve beyond permission prompts and domain/device block-lists, drawing inspiration from trust ecosystems like certificate authorities and package distributions.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

(ra, yk, il)