At the end of 2021, the Chrome team shipped some functionality that has the ability to make or break sites meeting the Core Web Vitals. So, let’s learn a little bit more about the Back/Forward Cache (aka bfcache), and what you can do to test if your website is compatible with it.

First of all, it would be remiss of me to give the Chrome browser all the credit here, when the other two main browsers (Safari and Firefox) have had this concept for quite some time now, though there are some subtle differences in all three implementations.

So, Chrome was playing catch-up here. However, as the world’s most popular browser and the only browser feeding back the Core Web Vitals information for any search ranking boasting, Chrome getting this (finally, some might say) is important. Plus, they’ve created some more transparency about this, both in documentation and tooling. Not to mention the many other Chromium-based browsers (e.g. Edge, Opera, Brave) will now also have gotten this functionality too.

With that caveat out of the way, let’s get to the guts of the article: What is the Back/Forward Cache and why does it matter so much? As its name implies, this is a special cache used to remember the web page as you browse away from that web page, so if you browse back to it later, it can load a lot quicker.

Think about the number of times you visit a home page, click on an article, then go back to the home page to view another article? Or you click back, then realize you forgot to make a note of something on that article, so click forward again. Similarly from cross-site navigation — think Google search results or the like and then clicking back. All those navigations can benefit from the Back/Forward Cache to instantly restore the page.

Didn’t The HTTP Cache Do All That Anyway?

Browsers have lots of caches, the most well-known of which is the HTTP Cache that stores copies of downloaded resources on a local drive for later reuse. Ensuring your website caches most of its assets for future uses has long been touted as essential for web performance. Sadly, however, it is not yet universal, but there are plenty of other articles written about that.

Using the HTTP Cache can avoid the need to download the same resources over and over again. Going back to the example of visiting a home page and then going to an article page. There are likely lots of shared resources (site-wide CSS and JavaScript, logos, other images, etc.), so reusing them from that home page visit is a good saving. Similarly, before the Back/Forward Cache came along, being able to reuse these assets if going back to the home page was a good gain — even if it wasn’t instant.

Downloading resources is a slow part of browsing the web no doubt, but there is a lot more to do as well as that: parse the HTML, see and fetch what resources you need (even if they can be gotten relatively quickly from the HTTP Cache), parse the CSS, layout the page, decode the images, run the oodles of JavaScript we so love to load our pages with… etc.

WebPageTest is one of the few web performance testing tools that actually tests a reload of the page using a primed HTTP Cache — most of the other tools just flag if your HTTP resources are not explicitly set to be cached. So, running your site through WebPageTest will show the initial load takes some time, but the repeat view should be faster. But it still takes a little time, even if all the resources are being served from the cache. As an aside, that repeat view will likely not be fully representative anyway. Loading with an empty cache or a completely primed cache are the two extremes, but the reality is that you might have a semi-primed cache with some but not all of the resources cached already. Especially if you navigate from another page on the site.

Here’s an experiment for you. In another tab, load https://www.smashingmagazine.com. Loads pretty quickly, doesn’t it? The Smashing team has done a lot to make a fast website, so even a fresh load (though this experiment may not be a completely fresh load if you came to this article from the home page). Now close the tab. Now open another new tab and load https://www.smashingmagazine.com again. That’s the reload with a fully primed HTTP cache from that initial load. Even faster yeah? But not quite instant. Now, in that tab, click on an article link from https://www.smashingmagazine.com and, once it’s loaded, click back — much faster yeah? Instant, some might say.

You can also disable the Back/Forward Cache in Chrome at chrome://flags/#back-forward-cache if you want to experiment more, but the above steps should hopefully be a sufficient enough test to give a rough feel for the potential speed gains.

It might not seem like that much of a difference, but repeat the experiment over a bad mobile connection, or using a heavier and slower website, and you’ll see a big difference. And if you browse a few articles on this site, returning to the home page each time, then the gains multiply.

Why is the Back/Forward Cache so much faster?

The Back/Forward Cache keeps a snapshot of the loaded page including the fully rendered page and the JavaScript heap. You really are returning to the state you left it in rather than just having all the resources you need to render the page.

Additionally, the Back/Forward Cache is an in-memory cache. The HTTP Cache is a disk cache. A disk cache is faster than having to fetch those resources from the network (though not always, oddly enough!), but there’s an extra boost from not even having to read them from disk. If you ever wondered why browsers need so much memory just to display a simple page — it’s partly for optimizations like this. And mostly, that’s a good thing.

Finally, not all resources are allowed to be cached in the HTTP Cache. Many sites don’t cache the HTML document itself, for example, and only the resources. This allows the page to be updated without waiting for a cache expiry (subresources normally handle this with unique cache-busting URLs, but that can’t be used on the main document, as you don’t want to change the URL each time), but at the cost of the page having to be fetched each time. Unless you’re a real-time news website or similar, I always recommend caching the main document resource for at least a few minutes (or even better hours) to speed up repeat visits. Regardless, the Back/Forward Cache is not limited to this as it is restoring a page, rather than reloading a page — so again another reason why it can be faster. However, this isn’t quite a clear cut, and there is still work going on in this space in Chrome, though Safari has had this for a bit now.

OK, But Is It Really That Much Faster For Most Web Browsing Or Are We Just Nitpicking Now?

The Core Web Vitals initiative gives us a way of seeing the impact on real user web browsing, and the Core Web Vitals Technology Report allows us to see these figures by site based on HTTP Archive monthly crawls. Some in the e-commerce web performance community noticed the unexplained improvement in January’s figures:

CRUX data for Jan-22 is out. Let’s see how various eCommerce platforms did this month. #webperf #perfmatters.

Change in % of Origins worldwide having good CWVs (compared to last month)@LightspeedHQ – 18% up@ShopifyEng – 9% up@opencart – 9% up@squarespace – 5% up pic.twitter.com/wbnDdGeRWl

— Rockey Nebhwani (@rnebhwani) February 9, 2022

Annie from the Chrome team confirmed this was due to the Back/Forward Cache rollout and was a bit surprised just how noticeable it was:

This is a bit surprising, but the improvement is user-visible; it is caused by the bfcache rollout (https://t.co/9raiXQaYwU).

What’s happening is that when a web page is restored from cache instead of fully loading, it skips all the layout shifts from load. Big CLS improvement!

— Annie Sullivan (@anniesullie) February 9, 2022

Although it is restoring the page from a previous state, as far as Core Web Vitals, as measured by Chrome, is concerned, this is still page navigation. So, the user experience of that load is still measured and counts as an additional page view — just with a much faster and more stable load!

Be aware, however, that other analytics may not see this as a page load and need to take extra efforts to also measure these. So for some of your tooling you may even have noticed a drop in visitor count and performance as these fast repeat views (which were measured), became even faster restores (but which potentially aren’t now measured), so your overall average page loads measured appear to have got slower. Again, I’ll refer you to Philip Walton’s article including a section on how bfcache affects analytics and performance measurement, for more information.

I’ve another more dramatic example, closer to home to share, but first a little more background.

Do I Need To Do Anything, Or Does My Site Just Get A Free Boost?

Well, this isn’t just some puff piece for the Chrome team — especially since they were late to the party! There is an action for sites to take to ensure they are benefiting from this speed gain because there are a number of reasons you may not be.

Implementing a Back/Forward Cache sounds simple, but there are a million things to consider that could go wrong. I’ve kept it reasonably light on technical details here (check out Philip Walton’s Back/forward cache article for more technical information), but there are many things that could go wrong with this.

Browser makers have to make sure it’s safe to just restore pages like this, and the problem is many sites are not written with the expectation that a page can be restored like this and think (not entirely unreasonably!) that when the page is navigated away from that the user isn’t coming back without a full page reload.

For example, some pages may register an unload event listener in JavaScript to perform some clean-up tasks under the assumption the user is finished with this page. That doesn’t work well if the page is then restored from the Back/Forward Cache. Now, to be honest, the unload event listener has been seen as a bad practice for a while now as it is not reliably fired (e.g. if the browser crashes, or the browser is backgrounded on a mobile and then killed), but the Back/Forward cache gives a more pressing reason why it should be avoided because browsers will not use the Back/Forward Cache if your page or any of its resources uses an unload event listener.

There are a number of other reasons why your page might not be eligible for the Back/Forward cache. Counterintuitively, for a web performance feature, some of these reasons are due to other web performance features:

- Unload listeners were (and in some cases still are) often used log data when the page was finished with. This is particularly useful for Real User Monitoring web performance tools — used by sites that obviously have an interest in ensuring the best performance! There are other better events now that should now be used instead that are compatible, including

pagehideandfreeze. - Using a dedicated worker to offload work from the main thread is another performance technique that at the moment makes the website ineligible for the Back/Forward cache. This is used by some popular platforms like Wix, but a fix for sites using Web Workers is coming soon!

- Using an App Install Banner also makes a site ineligible, which affected smashingmagazine.com (we’ll get back to that momentarily), and again supporting App Banners is being actively worked on.

Those are some of the more common ones, but there are lots of reasons why a site may not be eligible. You can see the complete list of reasons for the Chrome source code, with a bit more explanation in this sheet.

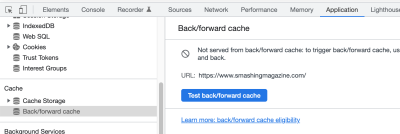

Helpfully, rather than having to examine each one, the Chrome team added a test to Chrome Dev Tools under the Application tab:

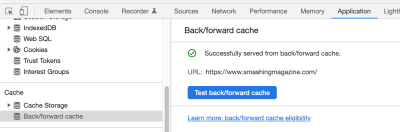

Clicking on that inviting little blue button will run the test and should hopefully give you a successful message:

If you are getting an ineligibility message, with a reason then it’s well worth investigating if that reason can be resolved.

Third-party scripts might be making your page ineligible, even if you don’t use those features directly in your code. As I mentioned above, unload event listeners are particularly common to some third-parties. As well as the above test showing this, there’s a Lighthouse test for this. Running a query on the HTTP Archive data yielded a list of popular third-party scripts used by many sites that use unload event listeners.

I’ve heard the Chrome team has been reaching out to these companies to encourage them to solve this, and many of the scripts logged in the above spreadsheet are older versions, as many of the companies have indeed solved the issues. Facebook pixel, for example, is used by a lot of sites and has apparently recently resolved this issue, so I am expecting that to drop off soon if that is indeed the case.

Site owners may also have power here: if you are using a third-party service that uses an unload event listener, then reach out to them to see if they have plans to remove this, to stop making your website slow — especially if it’s a service you are paying for! I know some discussions are underway with some of the other names on that list for precisely this reason, and I’ve helped provide some more information to one of the companies on that list to help prioritize this work, so am hopeful they are working on a fix.

As I mentioned earlier, each browser has implemented the Back/Forward Cache separately, and the above test is only for Chromium-based browsers, so even if you pass that, you may still not be benefiting completely in the other browsers (or maybe you are, and it’s just Chrome that’s not using it!). Unfortunately, there is no easy way to debug this in Firefox and Safari, so my advice would be to concentrate on Chrome first using their tool and then hope that’s sufficient for the other browsers as they often are more permissive than Chrome. Manual testing may also show this, especially if you can slow down your network, but that is a little subjective, so can be prone to false positives and false negatives.

Impact On SmashingMagazine.com

As readers undoubtedly have noticed, the smashingmagazine.com website is already fast, and they’ve published a number of articles in the past on how they achieve this level of performance. In the last one, which I wrote, we documented how we spent a huge amount of time investigating a performance issue that was holding us back from meeting the Core Web Vitals.

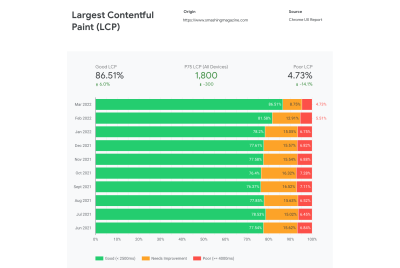

Thanks to that investigation we had crossed into the green zone and stayed there, so we were reasonably happy, as we were consistently under the 2.5-second limit for LCP in CrUX for at least 75% of our visitors. Not by much admittedly, as we were getting 2.4 seconds, but at least we were not going over it. But never ones to rest on our laurels, we’re always on the lookout for further improvements. They delayed some of their JavaScript in January leading to some further improvements to an almost 2.2-second CrUX number.

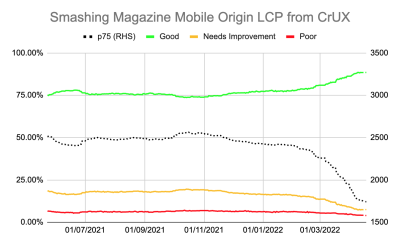

This website was initially failing that test due to the fact it had an App Install Banner. SmashingMazgazine.com is a PWA that prompts you to install it on the home screen for browsers that support that (Chrome on Android devices primarily). When I highlighted to the team in early March that this was holding them back from benefiting from the Back/Forward Cache that had recently been launched, they decided to remove some key parts of manifest.json to prevent the App Install Banner from showing, to see if this feature was costing them performance and the results were dramatic:

We can see the impact of the December and January improvements were noticeable but started to tail off by the start of March, and then when we implemented the Back/Forward Cache fix the LCP numbers plummeted (in a good way!) all the way down to 1.7 seconds — the best number Smashing Magazine has ever seen since the Core Web Vitals initiative was launched.

In fact, if we’d known this was coming, and the impact it would have, we may not have spent so much time on the other performance improvements they did last year! Though, personally, I am glad they did since it was an interesting case study.

The above, was a custom chart created by measuring the CrUX API daily, but looking at the monthly CrUX dashboard (you can load the same for any URL) showed a similarly drastic improvement for LCP in the last two months, and the April numbers will shop a further improvement:

Across the web, CLS had a bigger improvement with the rollout of the Back/Forward Cache in Chrome, but Smashing saw the improvement in LCP as they had no CLS issues. When investigating the impact on your site look at all available metrics for any improvement.

Of course, if your site was already eligible for Back/Forward Cache then you will have already got that performance boost in your Core Web Vitals data when this was rolled out in Chrome to your users — likely in December and January. But for those that are not, there is more web performance here available to you — so look into why you are not eligible.

Was there a downside to disabling the App Install Banner that was preventing this? That’s more difficult to judge. Certainly, we’ve had no complaints. Perhaps it’s even annoying some users less (I’m not an Android user, so can’t comment on whether it’s useful or annoying to have pop-ups on a site you visit encouraging you to install it). Hopefully, when Chrome fixes this blocker, Smashing can decide if they want both, but for now the clear benefits of the Back/Forward Cache mean they are prepared to give up this feature for those gains.

Other sites, that are more app-like, may have a different opinion and forgo the Back/Forward Cache benefits in favor of those features. This is a judgment call each site needs to make for any Back/Forward Cache blocking features. You can also measure Back/Forward Cache navigations in your site Analytics using a Custom Dimension to see if there are a significant number of navigation and so an expected significant gain. Or perhaps A/B test this? There are also a couple of interesting proposals under discussion to help measure some of this info to help websites make some of these decisions.

Test Your Website Today!

I strongly encourage sites to run the Back/Forward Cache test, understand any blockers leading to an unsuccessful test and seek to remove those blockers. It’s a simple test that literally only takes a couple of seconds, though the fix (if you are not eligible) might take longer! Also, remember to test different pages on your website in case they have different code and thus eligibility.

If it’s due to your code, then look at whether it’s giving the benefits over this. If it’s third-party code, then raise it to them. And if it’s for some other reason, then let the Chrome team know it’s important to you for them to solve it: Brower makers want user feedback to help prioritize their work.

If you don’t do this, then you’re leaving noticeable web performance improvements on the table and making your site slower for users, and failing to capitalize on any SEO benefit at the same time.

Many thanks to Philip Walton, Yoav Weiss, Dan Shappir, Annie Sullivan, Adrian Bece, and Giacomo Zecchini for reviewing the article for technical accuracy.

(vf, yk, il)